Reflections on The Origins of Proslavery Christianity

Charles F. Irons

Assistant Professor of History

Elon University

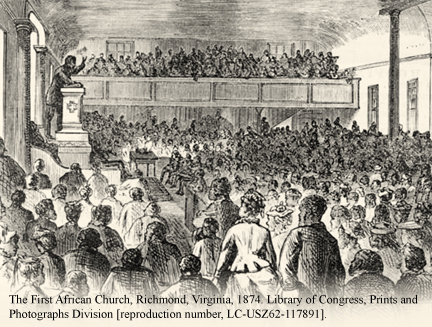

There are two First Baptist Churches in Charlottesville, Virginia, just as there are in many southern cities—one "black," and one "white." In fall 1993 I began attending the "black" First Baptist Church after a profound first meeting with its then pastor, Bruce Aaron Beard. There are many ways in which the year that I spent as a "watchcare member" of First Baptist was transformative, and one of them was in the window that it opened to me on the late antebellum world of Virginia evangelicalism. In particular, I wondered about the experiences of the 842 African Americans who were baptized members in good standing of Charlottesville's biracial First Baptist Church before they broke away in 1863 to form the congregation in which I was worshipping. Before the Civil War, more than half of the city's black residents—including both enslaved and free persons—had belonged to a church governed by white evangelicals who defended slavery as a divine institution. Fellowship and exploitation had coexisted in a mysterious way.

It did not take very sophisticated counting during my graduate training to realize that the tension-filled ecclesiastical situation in Charlottesville had been anything but unique. Across the South, black men and women worshipped together with the same whites who defended slavery. Contemporaries estimated that there were 468,000 black church members in the slaveholding states in 1860, a figure which—when adjusting for adherents—suggests that between 41 and 54 percent of all black Southerners attended a biracial church under white leadership (or a semi-autonomous black church supervised by whites). While black church membership probably fell significantly below 50 percent in the Gulf States, even using the most conservative estimates for numbers of adherents it is almost certain that a majority of black Virginians were church members by the late antebellum period. My initial research question for The Origins of Proslavery Christianity: White and Black Evangelicals in Colonial and Antebellum Virginia consisted of little more than a desire to understand how white southerners justified the enslavement of those with whom they professed spiritual brotherhood.

Since the white Virginians whom I studied modified the ways in which they defended slavery so frequently, the project early on became more fundamentally historical. In other words, the chief analytical task became charting and explaining changing patterns of interracial interaction and the corresponding changes in whites' proslavery arguments—rather than an exercise in theodicy or a speculative psychological exploration of white supremacists' psyches. Just as importantly, the emphasis on process and on the relational context for the formation of proslavery Christianity short-circuited questions about the intentionality of white evangelicals' use of religion to support slavery. It became much less important whether or not any individual white evangelical was self-consciously manipulating the language of Jesus to defend the peculiar institution, and much more important that white evangelicals in general found ways to accommodate the spiritual aspirations of black Virginians within their churches. By alternately encouraging, restricting, or redirecting the spiritual initiatives of the African American men and women with whom they remained in close ecclesiastical contact, white evangelicals convinced the vast majority of their peers that slavery and Christianity were easily compatible.

|

|

An exciting wave of scholarship on southern religious history in the late 1990s gave me powerful interpretations to engage and new methodologies to consider as I began my research in earnest. Christine Heyrman's Southern Cross was the highest profile work of the bunch, winning the Bancroft Prize in 1998. As taken as I was by Heyrman's energetic prose and by her insistence that evangelicals had to campaign actively in order to "win" the South after the Revolution, I was troubled by her reliance on itinerant Methodist sources and the way that she basically reaffirmed a narrative of evangelical compromise. While she added some exciting language about class and gender, she also affirmed Donald Mathews' contention in the wonderfully durable Religion in the Old South that white southerners around the turn of the nineteenth century betrayed the egalitarianism of early evangelicalism and prostituted their faith to material interests in slavery. But at precisely the same time, historians such as Jewel Spangler and Douglas Ambrose were revising Mathews' formulation, emphasizing instead the proslavery credentials of early white evangelicals. Moreover, in an exciting and parallel development, scholars such as Paul Harvey, Sylvia Frey, and Betty Wood were building on the work of Mechal Sobel, John Boles, and others and studying the transformative effects of interracial interaction among church members. As I tried to absorb and respond to all of this excellent material, my initial goal of understanding proslavery Christianity in the context of black/white relations expanded to become almost comically unrealistic—as I stated in the dissertation, it was to write an "intellectual and cultural history of all Virginians from the eve of the American Revolution to the beginning of the Civil War—one that included religious commitment as an analytical category in addition to those of race, class, and gender."

The primary benefit of this too-inclusive approach, which I more or less abandoned after completing the dissertation from which the book eventually developed, was that I began to see more clearly the relationship between ideological changes among white evangelicals and demographic and cultural changes among black Virginians. At first the patterns appeared coincidental, episodic, or confined to a few landmark events—the American Revolution and Nat Turner's insurrection each proved a watershed for both trajectories, for example. But the closer I looked, the more points of correspondence appeared—whites took ecclesiastical action on slavery at precisely the same time that more acculturated blacks joined their churches; whites sponsored colonization when black men enjoyed the highest profile and most freedom as ministers of the Gospel; and whites boasted most confidently about slavery's benefits when blacks joined biracial or fast-growing semi-independent churches in the late antebellum period. Mere correspondence between these events, of course, was not sufficient evidence for a causative relationship between developments within Virginia's African American population and the development of proslavery Christianity, so I began to explore these connections more intentionally. I quickly discovered that black Virginians made independent religious choices to which whites within the commonwealth's evangelical churches responded by modifying their actions and attitudes towards slaveholding.

I use the expression "actions and attitudes" intentionally, for I spent far less time on formal theology than I at first expected. Some of this represents a failure on my part, and the more theologically sensitive work of J. Kameron Carter, Stephen R. Haynes, and Mark Noll suggests that theological constructions of racial difference could have been a fruitful avenue of inquiry. But I was struck early on—both from my reading of the primary texts themselves and from the work of Larry Tise and Andrew Feight—by the essential continuity of the biblical proslavery argument, at least from the middle of the eighteenth century. For the period that I considered, from the so-called "First Great Awakening" through the Civil War, the vast majority of white evangelicals in the South believed that God had ordained slavery in the Old Testament, that Paul had explicitly affirmed it in his Epistles, and that Jesus had not challenged it in the Gospels. There was even a relatively stable corpus of proof texts, featuring prominently the infamous Pauline exhortations for servants to submit to their masters (various expressed, cf. 1 Corinthians 7: 20-24, Ephesians 6: 5-9, and 1 Timothy 6: 1-8, for example). An additional reason that I decided not to engage scriptural reasoning too closely is that I wanted, like so many other scholars in my cohort, to get at the "lived religion" of my subjects, many of whom did not articulate a formal scriptural rationale for their actions.

Indeed, sometimes the most important subjects, black Virginians, did not articulate much of anything in the historical record. While slave narratives and church records provided some clear black voices, I occasionally had to resort to the familiar strategies of reading against the grain in "white" sources or putting together numbers and other testimony to reconstitute the actions of black Virginians. This is not to say that the records were silent! On the contrary, one of the most powerful moments for me came as I stared at centuries-old Minutes for the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the Methodist Reading Room of Duke University's Divinity School. I was trying to reconstitute the number of black members in early churches and could not understand why the circuit with the highest number of black members (Surry, with 955 black members and only 814 white members) simply vanished from the records after 1793—and why neighboring Sussex (into which Surry merged) experienced a precipitous decline in black members at roughly the same time, from 1,069 in 1794 to 180 in 1796. I then noticed that James O'Kelly, who broke from the Methodists in 1792 and who penned his extraordinary Essay on Negro Slavery in 1789, had served as presiding elder over precisely these circuits (in addition to several others). Beyond a shadow of a doubt, black Virginians were very early making choices about which churches to attend based on the way that those churches addressed the issue of slavery. No wonder, then, that whites treaded so gingerly in the way that they discussed the peculiar institution in the late eighteenth century.

There is some irony in the fact that I emphasize so strongly the transformative nature of interactions between black and white evangelicals, because—as the above, more inductive example illustrates—I do not consistently show those interactions with the same fine-grained detail that other historians have managed to achieve over the past four years. Paul Harvey, as he explained in volume VIII of this journal, showed interracial interactions among black and white Christians in almost every imaginable context in Freedom's Coming. Closer to my own subject matter, Erskine Clarke won the Bancroft Prize in 2005 for his truly breathtaking work on the white and black families that surrounded Charles Colcock Jones, Liberty County, Georgia's famous missionary to enslaved persons. Clarke showed sustained interactions between the same individuals over several decades, capturing in the process the way that patterns of interaction (and not merely individual encounters) formed whites' and blacks' thinking about race, slavery, and their religious obligations to one another. In addition, Patrick Breen and Randolph Scully each completed brilliant dissertations on interracialism among churchgoers in the commonwealth while I was at work on the book. Scully's recent monograph, Religion and the Making of Nat Turner's Virginia, records in great detail the relationship between black and white Baptists for several decades after the Revolution in a dozen or so Virginia churches.

Taken together, these works (and other fine books not mentioned here) indicate that the emphasis on interracial interaction is part of the new orthodoxy in southern religious history. Indeed, while I sincerely regret that I did not manage to develop in depth as many black or white personalities as Clarke did, I think that all of the above texts nonetheless complement one another very well. I consider the relative strengths of my account that I cover so much time and document so many distinct shifts in whites' attitudes about slaveholding and about enslaved persons. Moreover, I retained a wide enough perspective that I could confidently identify when changes in perspective moved from localities within Virginia into the mainstream, thanks in large part to extensive reading in the denominational newspapers. Finally, there is plenty of evidence of interracial interaction in Origins of Proslavery Christianity, even if it is more episodic in nature than the relationships in the excellent longitudinal studies of Clarke and Scully in particular.

| |

|

The geographic focus on Virginia was a concession to practicality, but one about which I have not experienced many scruples. Holding the geographic boundaries constant to the South's largest and most important slaveholding state allowed me to pay more attention to change over time and to capture the remarkable versatility of proslavery Christianity. Furthermore, since Virginia exported so many white and black settlers, the analytical significance of the state is even higher. Nonetheless, I became attuned enough to differences among slaveholding states that I am very aware of the tradeoffs associated with the exclusive focus on Virginia. On a most basic level, it's worth asking the question: if white evangelicals responded so directly to the spiritual decisions of black southerners, then how might the story differ in other communities with different timelines of black spiritual activity (on the cotton frontier, for example, where church membership may have been lower; in Catholic communities in Louisiana; or in states where Methodists, not Baptists, claimed the highest proportion of African American members)? I think that there was an unmistakable trend towards interdenominational and interstate cooperation among whites in their thinking about slavery, especially from the 1830s, but (as the divergent courses of the Upper and Lower South during the secession crisis indicated) the process of homogenization was never complete. My awareness of the complexities that a wider angle might have revealed does make me wish that, Randall Stephens-like, I had shown more clearly the movement of these ideas across the South, integrating more effectively the Virginia story with the southern story.

Even though my initial question about the coexistence of fellowship and exploitation—or, as I put it in the acknowledgements, my attempt "to understand why the parable of the Good Samaritan fell on deaf ears for so many generations"—gave way to a more scholarly analysis of change over time, my conclusions are still fairly discouraging. They show how easily the best-intentioned individuals can construct institutions that reinforce rather than challenge inequality.

Click here to read the JSR's review of The Origins of Proslavery Christianity