"THIS BARBAROUS PRACTICE": Southern Churchwomen and Race in the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, 1930-1942

Southern gentle lady,

Do not swoon.

They’ve just hung a nigger

In the dark of the moon.

They’ve hung a black nigger

To a roadside tree

In the dark of the moon

For the world to see

How Dixie protects

Its white womanhood.

Southern gentle lady,

Be good! Be good!

— Langston Hughes, “Three Songs About Lynching,” 1936

“We the undersigned women . . . believe that the crime of lynching undermines all ideals of government and religion which we hold sacred and which we try by our lives and our conduct to implant in the minds of our youth. We recognize that all lynching will be defended so long as the public generally accepts the assumption that it is for the protection of white women.”

—Excerpt from “Pledge,” Southern Association of Women for the Prevention of Lynching, (1932)

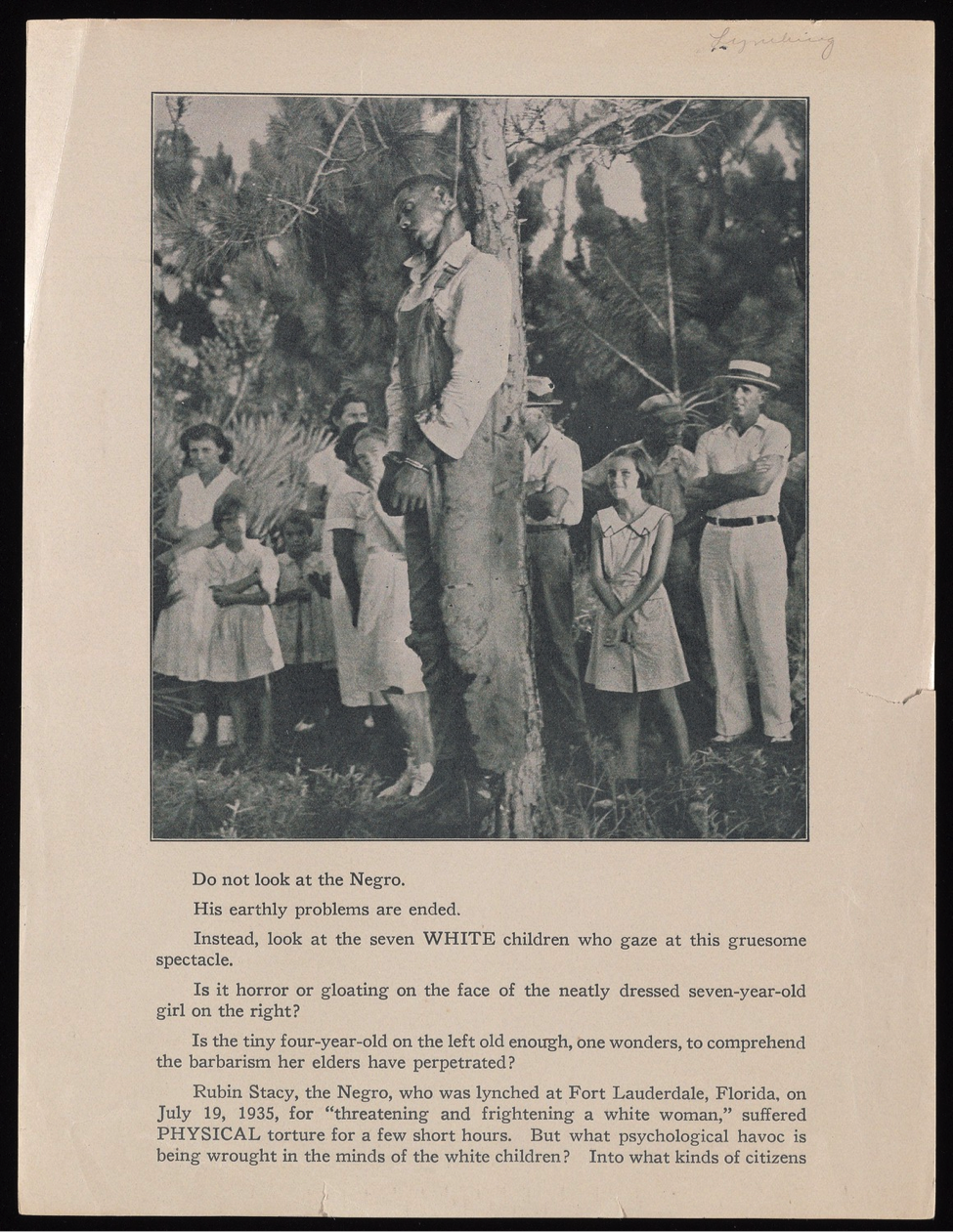

“Do not look at the Negro. His earthly problems are ended.” Such was the appeal of a circular issued by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in late 1935. Printed directly below a halftone photograph of Rubin Stacy, “the Negro” who had been lynched in Fort Lauderdale, FL, in July of that year for “threatening and frightening a white woman,” the N.A.A.C.P.’s petition was a calculated gesture. Of course folks would look at the lifeless body hanging in the center of the image dominating the page (fig. 1). Photographs of lynched corpses had long circulated as relics of the “barbarous practice,” to use a contemporary euphemism, but there were other people in the frame, and these were the bodies the N.A.A.C.P. wanted you to see: “Instead, look at the seven WHITE children who gaze at this gruesome spectacle.” Drawing our eyes—the power of the image still captivates—to the spectators, the text asks “Is the tiny four-year-old on the left old enough, one wonders, to comprehend the barbarism her elders have perpetrated? . . . Into what kinds of citizens will they grow up? What kind of America will they help to make after being familiarized with such an inhuman, law-destroying practice as lynching?” Lynching, here, was not a matter unique to the American South or to “the Negro.” It was a national scourge that threatened white Americans and the very success of American democracy. The flier’s question—“into what kind of citizens will they grow up” to be?—was intended to haunt anyone who recalled the gruesome photograph of Rubin Stacy.1

The N.A.A.C.P. circular was, among other things, a campaign flier pitching a direct appeal to the voting public to support federal antilynching legislation currently stalled in Congress. For more than a decade antilynching bills had languished in committees and been filibustered on the Senate floor. In March 1935, just months before the lynched Rubin Stacy was photographed with an audience of schoolchildren, a bill drafted by Senators Edward P. Costigan (D-CO) and Robert F. Wagner (D-NY) was presented with the enthusiastic endorsement of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary: “It is the opinion of the committee that the proposed legislation is ‘appropriate legislation’ to prevent the evil of lynching wherever in the United States that evil exists or may be committed” and that, leaning on the Constitutinal promise of the Fourteenth Amendment, “the measure is an aid to the several [i.e., all] States in assuring to their citizens the equal protection of the laws, both State and Federal, to which all citizens are entitled.” Still, the bill again succumbed to filibuster in early May.2 It was scheduled to come back to the floor the following session and the N.A.A.C.P. was marshaling public support, turning attention away from legislative stalemate by placing the burden of action—and the spark of inquiry—in the hands of everyday Americans: “What, you may ask, can YOU do?”

The N.A.A.C.P. flier attempted to rouse public attention by framing racially-motivated vigilantism as crime threatening white communities as well as black, as a scourge on democracy instead of specific murderous acts. As such, it worked to reinforce the categories of race that it ostensibly called into question, but it was hardly the first attempt to make the crime of lynching a national concern. Ida B. Wells-Barnett had begun her campaign against lynching in the late nineteenth century, and the first national legislation had been introduced in 1920.3 Still, the flier does mark a particular moment in time and found its way into the hands of thousands of Americans who were responding to the circumstances of their day. Two of these hands belonged to Jessie Daniel Ames, a Texas-reared former suffragette who since November 1930 had directed a group of predominately white southern women “agitating” to eradicate the “barbarous practice” and, most especially, the seemingly ubiquitous rationale that lynching was necessary to protect their own womanhood.4 Christened the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, the organization was successful in large measure only to the extent that it deflected the women’s direct political or legislative action and promoted longstanding commitments to community and, especially, education. In fact, unlike the N.A.A.C.P. and other antilynching organizations, the ASWPL deliberately denied “political involvement” and did “not support Federal legislation to eradicate lynching,” advocating instead that “the slow process of educating society to recognize and abhor the evils out of which lynchings grow is the only sure way to stop lynching.”5

It was one thing to advocate education over legislation—to appeal to citizens’ better angels rather than legal obligations—but even if the ASWPL stood firmly against the contested legislation as a matter of principle, their efforts were in no way sealed off from congressional activities. In February 1935, Caroline O’Day, Democratic representative from New York, argued “a woman’s viewpoint” on the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill before the Senate Judiciary subcommittee. O’Day represented the people of Rye, New York, and had spent extensive time abroad over the previous decades, traveling throughout Europe, South Africa, and India. Despite her best efforts to focus on the international ramifications of lynching—on “the prestige that we as a nation are losing in the eyes of the world”—at a hearing deliberating whether the crime of lynching warranted federal oversight, her testimony was bookended by subcommittee chairman Frederick Van Nuys reminding his colleagues that O’Day was “a native of the Southland.” “Now, I am from the South,” O’Day responded, “but I am not speaking for myself alone.” Pulling out an ASWPL pamphlet, O’Day proceeded to read the Association’s declaration against lynching as “an indefensible crime” that is “not confined to any one section of the United States.”6

Ironies aside, this episode tells us quite a bit about the political world of antilynching activism in the 1930s. The often torrid dalliance between activism and governance, the mishmash of associations with common objectives and competing solutions, and the slippage between regional identification and national imperatives each gestures to the difficult landscape in which Ames and her coterie were at work. But there is another, parallel story within the Association itself. Among the dozens of organizations supporting the Costigan-Wagner bill in the early 1930s through legislative action, religious organizations were far and away the most numerous—a roster that included the Federal Council of Churches, the Committee on Race Relations of the Society of Friends, the Social Justice Commission of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Nashville Pastors Association, the First Unitarian Church of Des Moines, and the National Baptist Convention, among dozens more.7 Given this grassroots association of religious bodies with antilynching legislation, it should come as no surprise that the ASWPL, too, depended heavily on religion, and especially southern churchwomen, in its organizational and ideological development. And yet the role of religion in the ASWPL, not unlike that of politics, was as contested as it was consequential. What follows is a story of American race, politics, and religion that beckons us to think anew about race relations and southern women’s activism in Roosevelt’s America.

The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching was borne out of an initial “Conference of Southern White Women” that convened in November 1930 at the Piedmont Hotel in Atlanta, billed as “one of the handsomest in this country” when it opened its doors thirty years earlier.8 This initial conference at the “palatial hostelry” was organized by Jessie Daniel Ames, head of “Woman’s Work” in the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, an Atlanta-based alliance of Southern blacks and whites organized in 1919 by Will W. Alexander, himself a former minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.9 Half of the twenty-six women invited to the Conference represented southern religious bodies—predominantly Protestant, although Gertrude Weil of North Carolina was scribbled in as “Jewish.” More significantly, of the twelve who signed the initial resolution of the Conference “to repudiate and condemn” the conventional “defense of lynching”—the “protection” of their own womanhood—nine were officially aligned with southern denominational woman’s missionary divisions and “formed the nucleus” of the emerging antilynching association.10

Archival fragments record thousands of women over the course of the 1930s who wrote letters to the Association and to local editors, signed their names to antilynching pledges, and committed themselves to “programs of education” in their local religious and civic organizations. To provide just a glimpse here, a 1937 pamphlet boasts that a mere six years after the original meeting of “twelve women and no organization,” the ASWPL had on file “37,267 men and women living in 2,912 towns and 1,059 counties” across the South. More telling is that the Association had aligned with more than eighty state, regional, and national organizations “with an estimated Southern membership of over four million.”11 If these numbers seem inflated, they probably are. But the Association’s organizational model was deliberately against “perpetuating” a new organization and their work was to be “carried on through already existing women’s organizations.”12 Such a structure undoubtedly creates tangles in the institutional history of the movement and muddles any attempt to pinpoint membership roles, but it also provides a helpful model for mapping the unsettled boundaries of women’s civic and devotional labors. Were the activities and agitations of the ASWPL religious or political? Were they progressive or conservative? Did they act to end lynching or to promote the political agency of southern white women? These questions, despite the abundance of archival evidence that exists, are more generative than they are answerable. Even the most socially progressive among the women involved in the campaign to end lynching maintained a relatively conservative theology that challenges conceptions of social activism as a stronghold of the theologically liberal. Seemingly paradoxically, most of the women in the antilynching campaign navigated between conservative theological anthropologies that placed responsibility for redemption on individuals, and social anthropologies that emphasized corporate ethics. 13

An undated memo titled “Points to Emphasize in Presenting the Movement against the Crime of Lynching” captures this tension between religion and politics in the movement’s self-narration. The first point to emphasize in explaining the “basis for the movement” was “respect for the social teachings of religion.” Coming before “respect for Federal and State Constitutions,” “respect for the courts,” and “respect for society,” the memo underscores the primary role of religion in framing the Association’s mission. However, the document seems primarily concerned not with a theological or devotional critique of lynching but with a moral infraction extending not from the crime of lynching itself but from its affront to women’s political legitimacy. “Why are Southern women active?,” the memo asks, answering “because public opinion is trained to place Southern white women and lynching in the same brackets of thought, using the dignity and virtue of the one to cloak the blackness of the crime of the other.” What is more, the efforts of women’s organizations to promote “better citizenship” through their many bureaus, departments, and committees are compromised—their “effectiveness is largely nullified”—because women’s “sincerity is open to question by other nations and races who do not lynch.”14

The ambiguities surrounding the Association’s motivations demonstrates that any attempt to understand their activities requires an attentive ear to the intersecting discourses of race and gender that guided their campaign. Far from being merely abstract notions, the women of the Association navigated their social, political, and religious environs through coordinates calibrated to underlying logics of “whiteness,” “the Negro,” and “womanhood.” The lectures, letters, and publications of the Association yield only a partial glimpse of how religion, race, and gender intersected the antilynching campaign. During the 1930s, for instance, race was a highly contested category under a state of constant revision and it would be far too simplistic to assume that it carried a stable definition within the movement, let alone throughout the nation. What is clear is that the Association, like other cultural arenas in the 1930s, was invested in the racialized designation of “white” Americans as much as “the Negro.”15

Still, even if the phrase “white women” was peppered throughout the Association’s internal documents and public declarations, and thus indicates the importance of this signifier to the movement, the metrics of race were hardly of equal weight either within the organization or outside. Racial categories of whiteness and blackness were frustratingly unstable, which made the cultural mechanism of “chivalry” a hard tide to turn. Langston Hughes’s “Three Songs for Lynching,” first published in 1936, for instance, echoes the themes of white womanhood and protection that populated the Association’s public and private discourse. But Hughes’s appeal to the “Southern gentle lady” plays with the themes of race and gender to very different effects, indeed reinforcing the brutal logic of lynching as a mechanism that “Dixie” employs to “protect / Its white womanhood,” and his plea to “Be good! Be good!” a hard jab at the presumed innocence of the “Southern gentle lady.”16 To her own credit, Ames acknowledged the limitations of her organization’s critique of “public opinion” when she wrote to an inquisitive New Yorker in 1935 that “we represent only a very thin top crust of public sentiment in the South even among the women.” This “top” position, she continued, was constantly challenged by the Association’s fellow southerners in ways that could only have been taken as discouraging: “There has not been a speech made by [any one] of us that we have not had women in our audience who have either walked out on us or have stayed to tell us that lynchings, under certain circumstances, are necessary.”17 Thus as much as the Association presents a different lens on race and gender in southern religion and politics, the measure of their “success” is a fraught-ridden metric. Rather than dwelling on the ultimately unanswerable—or at the very least chronically provisional—questions of historical success or contemporary influence, it is far more productive to explore the churchwomen’s activities as they shaped gender and race by mobilizing and negotiating the cultural systems into which their activities were inscribed. Two cultural arenas where these intersections were particularly solvent were the debate over the southern interpretive tradition of “chivalry” and the one-act antilynching plays that the Association sponsored in 1936. After establishing the intimacy that existed between churchwomen and the antilynching campaign demonstrated in the adoption of a “program of education” rather than an overtly “political” agenda, the article turns to closer examinations of chivalry and lynching plays in order to contextualize the dynamic interplay of religion, race, and gender in the ASWPL.18

“To Hasten The Kingdom Of God”: Southern Churchwomen, Social Action, And Local Accountability

Writing to Ames shortly after the Association was first organized, Mrs. M. W. Riddick expressed that she “should like to be associated with any movement whose object is to stamp out lynching and to hasten the kingdom of God among men.”19 For Riddick, like many other women affiliated with the Association, these civic and devotional objectives were inseparable. The catch was how to render them effective in a social and political arena without compromising the engagement of politically conservative allies. Federal antilynching legislation was in and out of Congress throughout the decade, and it would seem commonsensical that an association whose main objective was eradicate the “black spot on America’s soul” would immediately endorse such policy. But the Association was comprised of several constituent members who sponsored quite disparate positions when it came to politics, regardless of how uniform they were in their desire to abolish lynching. Demonstrating the critical role of churchwomen in the campaign was the early concession that endorsing legislation of any variety would immediately alienate “some women, particularly in the churches, who are opposed to what would seem to be politics.” Six years after the Association was first formed, Ames delivered an authorized history of the movement for those newly recruited, an oration that effectively transformed the Association’s apocryphal origins into inevitable trajectory. One of the points of this speech was the Association’s decision “not to go in for legislation” because, as Ames contended, through such direct appeals to governing bodies “we would lose almost at once the possible support of the Southern Baptist women, we would lose instantly the support of the Southern Presbyterian women, we would lose the support of the Episcopalian women.”20 In this context, political expediency was contingent on appearing apolitical.

Careful not to agitate the “consecrated women,” the Association attempted to mute theological differentiations among its members by situating “respect for the social teachings of religion” as a “basis for the movement,” a move that simultaneously marked the significance of religious commitments and skirted (potentially divisive) theology.21 At least that was the idea. As with Riddick, for most women the theological and the social were indistinguishable. Southern Baptists and Methodists had long since been engaged in “social Christianity” to varying degrees, but the antilynching campaign was more problematic for Southern Presbyterians. Janie W. McGaughey, Secretary of Woman’s Work in the Presbyterian Church in the United States (the southern body), had been active in the Association as a “representative at large” since 1931. Several years later she wrote to Ames, who had raised concern about the relative lack of Presbyterian support, confirming that “there is no question about the interest of Presbyterian women in the program of education to prevent lynching.” But, McGaughey continued, “the matter about which there seems to be a misunderstanding is one that is very closely linked up with a conservative position of our Church regarding social action.”22 Ames would fret over the Presbyterians throughout the Association’s existence. But she and the Central Council—composed of women from “Southwide” religious and civic organizations and “outstanding individual women at large”—were nevertheless sensitive to the “point of fact” that “if we could get the women to commit themselves to the program of the Baptist, Methodist or Presbyterian Churches, we would have made great progress. The Methodist and Baptist Churches go into the smallest communities, when no other organization will be found there.”23 Religion was important to these efforts not only for providing a moral framework of political critique, but also for the extensive denominational network throughout the American South.

This sentiment points to the organizational structure of the Association, and particularly the critical role that southern Protestant denominations played in the distribution of the antilynching message. First, the Association’s interest was not primarily to garner the support of women in large cities, women who in most cases would be not only peers of Central Council members but also the most likely candidates to sympathize with the cause. Instead, as a 1933 memorandum indicates, “the Association hopes to have this year from each state one thousand names of women living in towns of five thousand or less – the smaller the town the better.”24 It was understood by the Council that lynching was primarily the pastime of rural (and often impoverished) communities. Moreover, by the early 1930s, confidence in the efficacy of legislative reform had been weakened by the repeal of Prohibition. Imbibing the lesson of the Twenty-First Amendment, Ames emphasized that “public opinion must be favorable to any law which requires local enforcement. That kind of public opinion against lynching is fundamental. For this we work.”25 Thus, in order to ease the support of churchwomen’s organizations and to shape public opinion in favor of their position, the women of the Association devoted their efforts to a “program of education.”

Second, it was precisely because affiliation did not entail legislative agitation that the women’s societies of politically conservative Southern denominations were granted greater latitude to join the Association’s efforts. Thus it was that by November 1932 the Association had secured endorsements from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, the National Council of Jewish Women, the national Young Women’s Christian Association, and the Woman’s Missionary Union of the Southern Baptist Convention, in addition to Woman’s Societies of Methodist conferences in eight of the thirteen southern states, and the Woman’s Missionary Unions of the South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas Baptist Conventions.26 The bold print of denominational representation, however, was that the women were “invited . . . not to represent their organizations [to the Association], but to represent the movement to their organizations.”27 Una Roberts Lawrence, president of the Woman’s Missionary Union of the Southern Baptist Convention throughout the thirties, put a different spin on the issue of representation when she emphasized “one of the assets that comes out of this denominational machinery” is that “an issue like this [lynching] vitalizes machinery.28

Despite these intentions, the distinction between representing one’s organization and representing the Association to one’s organization was difficult to maintain in the course of conference deliberations and its attending communications. Ames herself muddled the distinction when she wrote to Louise Young of Nashville that, “as for sufficient representation from Baptist women, I do not feel that anybody else is needed for [Lawrence] is the whole Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union in herself.”29 Nevertheless, in addition to demonstrating the critical role that southern churchwomen’s existing organizations played in broadcasting the antilynching campaign to regions of the South otherwise closed, this stipulation underlined the Association’s program of education by emphasizing a centrifugal organizational structure that ultimately landed the program’s efficiency in local relationships of heightened accountability.30

Even as the governing structure was quite clear on denominational representation, there was no provision against sanctifying the deliberations through theologizing the Association’s role in the antilynching campaign. Frequently in proceedings, religiously-charged language registered a more civically-pious than theological tone, as when Kate Mills mentioned that her role was to ask her auditors “to become familiar with the facts” about antilynching legislation and to “do their part as Christian Citizens.”31 Nevertheless, conversations at the annual meetings were peppered with statements that evoke theological imperatives in addition to devotional practices or idioms of piety. Ames’s claim at the 1930 meeting that “after all, we who commit the sin of ommission [sic] are just as guilty as the one who commits the crime,” is one such example.32 Even if this oblique reference to the teachings of the gospel of Matthew in the Christian scriptures was idiomatic, it nevertheless indicates a baptizing of the women’s deliberations.33

Of course religious language was frequently far more direct. During the afternoon session of the same meeting, Jennie Moton, whose husband Robert Russo Moton had succeeded Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee, entreated the conference to “get together and find a way out” of the lynching problem. “In so doing,” she continued, “we will directly help to bring to the South of ours that we love so dearly, a life that Jesus Christ died to establish among his children here.”34 In the published Minutes of this meeting, Moton’s oration is followed by a transcription of Matthew 7: 24-27 of the Christian scriptures, although it is unclear whether Moton quoted this passage at the meeting or whether it was subsequently added. The verses read:

Therefore whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock. And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.35

Was Moton, a prominent African American woman, urging her predominantly white peers to greater resolve, to build their efforts on a surer foundation? Was she subtly registering her concerns about the guarded approach the women were taking? While white men and women were lynched as well, particularly in the 1880s and 1890s, 89% of persons lynched between 1926 and 1937 were of African descent, rocking racial communities in very different ways.36 Nevertheless, it does seem as though Moton shared points of commonality with her fellow conferees. In addition to sharing a regional identity—the “South of ours that we love so dearly”—Moton also grounds the committee’s efforts in a shared narrative history, presuming that the passing reference to Protestant logics of redemption—“a life that Jesus Christ died to establish”—would be picked up by those who had ears to hear.37

In addition to her hermeneutical contribution, Moton’s presence at the afternoon session is important to note because it signifies the relationship that remained between the Commission on Interracial Cooperation and the Association of Southern Women throughout the 1930s and, more importantly, the relationships that were developed among women affiliated with both organizations. Although neither the CIC nor the Association drew exclusive support from southern denominations, the ranks of both organizations were filled by women who were deeply involved in both traditionally white and traditionally African American religious bodies. Shared narrative traditions rooted in Christian scripture and Protestant reading habits provided points of continuity between African American and white women engaged in antilynching activities during the 1930s. And while it is all too easy to overstate these continuities, denominational and theological legacies nevertheless equipped both white and black Protestants with habits for perceiving and navigating their social and political environs.

Within the Association, all three of the largest white Southern denominations were represented among its members. Southern Methodists, however, far outnumbered Baptists and Presbyterians in pledges and signatures, which in many cases serve as the only record of “on the ground” support. “Signatures are of the greatest importance,” an early memorandum emphasized, “Signatures of ministers. Signatures of editors. Signatures of law enforcing officers. Signatures of business and professional men. Signatures of women.”38 We should certainly exercise caution in using these pledges as a sole barometer of participation. Una Roberts Lawrence snidely commented on this fact when she reminded her colleagues that “the reason there were not more Baptist signatures is because Baptist women just did not have a precedent for signing things.”39 Whether Methodist churchwomen merely had a penchant for “signing things” is beyond my scope here, but Lawrence’s reminder does hearken the simple truth that the women of the Association had been trained by their various social and religious traditions in different habits of conduct. Methodist churchwomen had been organizing themselves for domestic “missions” since well before the Woman’s Department of Church Extension (the precursor to the Woman’s Missionary Council, formed in 1910) was established in 1886, and had been specifically engaged in “race-relations” since 1920.40 Moreover, according to Louise Young, who directed the Department of Home Missions of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South in the 1920s and served as a Tennessee representative to the Association in the 1930s, “home missions” departments “for the old southern church meant race relations really.”41 Thus while pledge signatures might have overrepresented Methodist churchwomen in relation to the tasks actually performed by churchwomen representing a broader spectrum of denominational bodies, for some within the Association this historical precedent of organized race-relations explained the more active—and thus better documented—response.42

Before turning to the logics of race and gender that were inherited and negotiated in the Association’s public and private exchanges, it is important to reiterate that religion was hardly uncontested within the antilynching campaign. However much the churchwomen shared in their theological orientations, there was plenty to distinguish them from one another as well. But the most explicit contests over the meaning of religion were in discussions of how evangelical Protestantism might actually be contributing to the epidemic of the barbarous practice. Only months before the initial meeting at the Piedmont, the associate secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Walter White, had indicted southern evangelical Protestantism for its conspiratorial role in the lynching epidemic. “It is exceedingly doubtful if lynching could possibly exist under any other religion than Christianity,” White asserted in his study Rope and Faggot, and further argued that “the evangelical Christian denominations have done much towards [the] creation of the particular fanaticism which finds an outlet in lynching. . . . Foul pages in American history have been written by means of lynchings and burnings in those very states which most vociferously have adhered to evangelical Protestantism as represented by the Baptist and Methodist Churches.”43

Rope and Faggot, to be sure, “a historical and psychosocial book” that White had completed while on leave from his duties at the N.A.A.C.P. in 1928, was in the estimation of historian David Levering Lewis, “critically well-received and widely read . . . but not memorable.”44 Will Alexander, the Executive Secretary of the CIC, however, had evidently read White’s study before he delivered an address to the Conference of women in 1930. “Now I don’t agree with Walter White when he says that the religious Methods of the Methodists and the Baptists produce lynchings,” Alexander leveled, “but it does seem that the religious percent of Methodists and Baptists do little to prevent it.” Despite critiquing White’s suspicion that evangelical Christianity caused lynchings, Alexander nevertheless claimed that “the more Baptists and Methodists your population has, the more lynchings you are likely to have” and further that “in the lynching section of Georgia Methodist and Baptist own the land and people.”45 Like her colleague Will Alexander, Ames was hardly an enthusiastic supporter of Walter White—the two would butt heads in the early forties when, as executive secretary of the N.A.A.C.P., he matched an enthusiasm for federal antilynching legislation that Ames channeled toward educational programs. But the correlation between evangelical Protestantism and outbreaks of lynching was convincing to her as well. During the January 1936 meeting, noting an escalation of lynching in the summer months, Ames hypothesized on “the possible connection between lynchings and old-fashioned revivals.” Thus a part of the program adopted for the summer of 1936 was “to go to every community in which there has been a prevented lynching or a lynching between the 15th of June and the 15th of August, find out when the revival was held, the type of sermons, general class of songs sung, and all the other things we can learn about the psychological effect of songs on that community, and how near after the revival these eruptions took place.”46

If these investigations were conducted, the results are well hidden. But it is significant to note that six years after the organization formed—six years of intense cooperation with southern bodies of Methodists and Baptists—that the Association had yet to abandon a possible connection between evangelical Protestantism and lynching. If nothing else, the persistence of this logic suggests that religion was itself a highly contested category in the Association’s program of education. On the one hand, religion was approached as the framework from which to condemn and eliminate lynching and, on the other, it was understood to generate and sustain the racialized animus that lynching manifested. Regardless of how it was mobilized, religion was not an independent variable, but was thoroughly intertwined with notions of race and gender. The ties that bound religion, race, and gender were evident throughout the Association’s words and deeds. But perhaps nowhere were these connections more explicit than in the amateur one-act antilynching plays that the Association solicited from their ranks late in the decade. Heavy-handed and often quite coarse, these plays nevertheless captured the Association’s pageantry of race and concomitant critique of chivalry.

The Pageantry Of Race

From the earliest days of the Association, categories and classifications of race were bound to habits of perception that were shaped by religious sensibilities. If, as Louise Young contended, “home missions . . . meant race relations really,” it was equally true that the antilynching campaign was a sort of racially-inflected millennialism in which religious and civic order was bound to the eradication of race-based violence. Laura Dell Armstrong echoed Riddick’s earlier sentiments—“to stamp out lynching and to hasten the kingdom of God among men”—eight years later when she wrote in an editorial for a publication of the Southern Baptist Women’s Missionary Union that the ASWPL “should command the deep interest and hearty cooperation of southern Baptist women.” Echoing Angelina Grimké’s Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, the little pamphlet that scandalized the slaveholding south in the 1830s, Armstrong’s editorial massaged the W.M.U.’s “distinctive [field] of missionary promotion” into a vision of the “full exercise of the holy privilege of Christian citizenship” and implored “Christian women” to embrace their “clear and definite obligation as Christian citizens to see that the spirit of Christ permeates every avenue of life. . . . In the home, the community, in national and international relations, cooperation with others is essential if our world is to be made more Christ-like.”47 For all of her impassioned advocacy of the demands of Christian citizenship, Armstrong stopped short of conflating personal salvation with social progress or racial cooperation. In an address to Baptist women in 1932, however, Ames completed the circuit. “She urged Christianity in our dealings with our fellowman,” the Richmond News Leader reported, “she spoke of the need for cooperation among peoples of other races, and especially the Negro” and “closed by saying the kingdom of God can be translated by our attitude toward our brother.”48 The distinction here is minor—perhaps one of degree rather than kind—but it illuminates the women’s exercised caution around matters of religion, lest these seemingly benign theological variations create fissures in their concerted efforts. Race, like religion, both permeated the Association’s efforts and was carefully avoided. Armstrong’s editorial and Ames’s address both explicitly mention race relations in their appeals but avoid the racialized mechanics of lynching—a circumlocution that was replicated throughout the Association’s public and private discourse.

As part of its educational versus legislative approach, the Association had early agreed that “we would have to insist that our concern was with the crime of the lynchers instead of their victim.”49 This emphasis worked to mute discourses of race even as it amplified the cultural work that such discourses performed. For instance, in November 1934, Sarah Morrison, the editor of an Episcopal lay society’s magazine, requested that Ames contribute to a forthcoming issue on the “study of the Negro in America.”50 Ames’s response emphasized the role of churchwomen and the devotional ethos of the campaign but failed to mention “the Negro” at all. The only racialized term Ames used in her five-paragraph response, in fact, was in the phrase “southern white women.” The thrust of Ames’s response displaced Morrison’s editorial aims and recentered on the work of the Association. “There is no greater evidence,” she wrote, “than the action of organized church women in leading this movement against a crime which was conceived in economic greed and protected by Southern chivalry.”51 In both their nominal and adjectival senses, the categories of “white” and “Negro” were contingent on practices of perception that were rooted in interpretive traditions of representation and recognition. At first glance, one is surprised by the relative lack of discussion of race—where was “the Negro” in this campaign against lynching? A deeper reading of the Association’s conference minutes, however, reveals a deliberation over the precise contours of “race relations.” Thus while black Americans were seldom addressed in the Association’s public discourse of lynching, these private deliberations reveal that such conversations were rooted in the negotiation of inherited traditions—such as biblical reading practices and regional and national narratives—that rendered them intelligible.52 Among the most salient of these interpretive traditions, however, was the notion of “chivalry” that Ames invoked in her response.

The initial “conference of southern white women” convened nearly forty years after Ida B. Wells had exposed “the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women” in an 1892 newspaper editorial that was subsequently reprinted in her study of lynching, A Red Record. Although the resolutions “to repudiate” the myth that lynching was “necessary to the protection of womanhood” were as swift in their indictment as they were sluggish in formulation, the antilynching campaign of the 1930s differed significantly from Wells’s campaign, particularly in that it was less concerned with racial reform per se than with disabusing the mythic rationale for “the unspeakable crime.”53 The Association’s resolutions were reflected in the pledges that were taken into churches, Parent-Teacher Associations, and civic organizations throughout the South. Effectively extinguishing the “halo of chivalry” that had hitherto mollified the brutality of the practice in the imaginations of many white southerners, the pledge acknowledged that “all lynching will be defended so long as the public generally accepts the assumption that it is for the protection of white women.”54 As even the most casual familiarity with ASWPL documents will attest, most references to the women of the Association use the modifier “white.” An undated document outlining “suggested points in presenting [the] purpose” of the Association, however, uses the term “Anglo-Saxon” to describe the “racial origins” of the South.55 By drawing on the terminology of “Anglo-Saxon” rather than, for instance, “white” or “Caucasian,” each of which were more indicative of the racialized parlance of the 1930s, the Association ostensibly signaled an allegiance to an inherited interpretive tradition that worked to reinforce the mythic past of the American South even as they aimed to disabuse their neighbors of the racialized calculus of Southern chivalry.56

But such an allegiance was tenuous at best and perhaps more accurately a vacant capitulation to operating norms for reasons of expediency—the mere utterance of the term Anglo-Saxon, in other words, was shorthand for the racialized heritage of the American South that the Association wanted to air out. Undoubtedly the churchwomen of the Association retained various degrees of privilege associated with whiteness, most often exemplified in their “maternalistic” postures toward impoverished and disenfranchised African Americans. One member of the ASWPL Central Council voiced this maternalism when she suggested that “thro Bible Study clubs, much can be done to establish contacts with Negro mothers and to help them.” But this maternalism was in a state of flux. Mrs. James R. Cain, for instance, made this appeal to the Association: “We white women do not need to develop an attitude of helping the Negro so much as we need to work for a recognition among our own people of the changing moral status of Negro women.”57 Notions of race, then, certainly motivated these “white women” in their “agitation,” although it is hardly sufficient to relegate their thoughts and actions to the analytically stultifying category of “racism.” Such a move undoubtedly masks the more complicated cultural work being performed through a racialized vocabulary. Allowing the possibility that the Association was engaged in complicated notions of race and gender is not a method of dismissing the pernicious effects of airs of moral superiority—but it does grant license to explore alternative interpretive paradigms.

One such approach was to challenge the uncritical extension of the most ubiquitous defense of lynching by fracturing the ideal of “Southern womanhood.” Redefinitions of “womanhood” were wrapped up in their critique of chivalry, a point illustrated by the denial of “womanly” characteristics to those who voiced opposition to the Association’s campaign. In May 1937, Frederick Sullens, editor of the Jackson [Mississippi] Daily News, forwarded to Ames a rather nasty letter he had received from one “Mrs. E. S. Cook” of Montgomery, Alabama. Upon receiving the opinion piece, Ames promptly contacted Elizabeth Greeson, who was affiliated with the Woman’s Missionary Society in Birmingham, and asked her to sleuth it out. Greeson’s first attempts—skulking around the Post Office, perusing the City Directory, telephone books, and church directories—proved unsuccessful. Two weeks later, however, she was rewarded. “As I stood at my box reading a letter,” Greeson wrote, she saw a letter deposited in a box near hers that was “addressed to Miss Ethel Cook so I . . . decided to go more often to the Post Office to see if there were any chance of seeing the owner. Today I was rewarded and she looks very much as I would have pictured her, tall, gangly, oddly dressed, very peculiar looking and . . . looked as if she were . . . about half crazy.” Ames was elated. “You missed your calling,” the director later told Greeson, “you should have gone into the Secret Service.” Replicating Greeson’s attempt to mitigate the heft of sentiments like Cook’s in the scales of public opinion, Ames assured that “almost any time that we have had an opportunity to trace letters of this kind back to their source we have found the writers to be quite like the woman that you have described.”58 The portraiture of antagonistic Southern white women as “gangly, oddly dressed,” and “crazy” was certainly a potent strategy of representation—working to diminish their opinions by questioning both their womanhood and their sanity. Working to reinforce the Association’s repudiation of their complacency with the logic of chivalry, moreover, this strategy of representation undermined the very “womanhood” that demonstrations of chivalry espoused to protect.

The Association’s disaffection from dominant interpretive traditions was also demonstrated by a companion resolution adopted at the first conference, in which the women expressed that they “deplore[d] making the Birth of a Nation into movietone.” D. W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman had, by by the late 1930s, become a candidate for the “talky” revolution. The women of the conference were appalled. “Recalling with horror,” the telegrammed resolution thundered as only a resolution lacking prepositions, definite articles, and verbs can thunder, “increase mob violence follwing [sic] showing as silent film with emotional appeal we feel with added effect of human voice consequences will be even more tragic and appeal to . . . prevent this picture being shown throughout Southern States.” As the first film to promote the Southern virtues of chivalry—and the racialized connotations that it entailed—Birth of a Nation remained the quintessential iconography of white supremacy in American popular culture through the 1930s, and arguably beyond. The antilynching conference’s appeal to Alice Ames Winter, former president of the Federation of Women’s Clubs and current director of community service for the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America at the time of the resolution, positioned the nascent Association in no equivocal terms in opposition to the racialized logics of Southern chivalry.59

Whereas whiteness was debated in the discourse of chivalry and the displaced arena of Fox Movietone, “the Negro” was rendered a spectacle in the pageantry of anti-lynching plays. To be sure, not all discussions of African Americans within the Association were occasioned on the stage. “Negro womanhood” was frequently a topic of discussion in the annual conventions and many of the churchwomen were engaged in “race-relations” within their denominations, particularly Southern Baptists and Methodists. Nevertheless, representations of African Americans in the one-act plays, and particularly the conversations about their production and reception, are an important site for teasing out the interpenetrations of race and gender in the Association’s public discourse. In 1936 the Association sponsored a one-act play contest for amateur playwrights as a means of generating public awareness and fresh “propaganda” for their campaign.60 Walter Spearman, a professor of English at the University of North Carolina, and Ann Seymour, a junior high school teacher from Palestine, Texas, took first- and second-place honors, respectively. Both of the prize-winning plays evince a rendering of popular (if caricatured) religious idioms and stylistic conventions. Seymour’s play, however, featuring an all-black cast, brings to the surface some of the deep-seeded tensions within the Association. The main character of the play, entitled “Lawd, Does You Undahstan?,” is “an old Negro woman” named Aunt Doady, and the scene is her cabin at dusk as a group of younger folks are on their way to an evening church service. It quickly becomes clear that Aunt Doady is revered by the younger crowd as one of highest moral and spiritual integrity—“Aunt Doady ain’ quite lak de res of us,” one character waxes, “She’s mo’ lak a saint, dat’s what!” The play climaxes, however, when Aunt Doady, recalling the lynching of her son, empties a jar of cyanide into the coffee that her grandson, Jim, gulps down as he scrambles to escape a mob in his pursuit.61

Ames praised Seymour’s play for presenting “the effects of lynching upon a Negro woman,” indicating that “this is something that we want to emphasize in our future programs.”62 But Seymour’s characters were not merely representations of Southern black men and women, they were crafted figures of a white Southern Baptist woman’s imagination, informed by habits of perception and practices of recognition. Drawing on conventions of representation of African Americans, Seymour’s stage directions specify that Doady’s “black, wrinkled face has the rather mournful tranquility found on so many black faces: a calm acceptance of fate” and that “the voices are soft and melodious and the vowels are much plainer than the consonants.” But racial dynamics were not only a part of theatrical representation—they also figured quite explicitly in the play’s reception. The first indication that Seymour’s all-black cast was going to generate complications was the remark of one of the judges that the “white actors whom we want to produce the winning shows before schools, and little theatre groups will not portray Negro roles sympathetically. They may wish to do so, but they can't.” Rather than dismissing the possibility of blackface productions—which, less than a decade after the release of The Jazz Singer and in a world where minstrelsy still lingered as a viable form of entertainment was certainly not inconceivable—these comments pointed to something deeper. “The roles are remarkable studies,” the judge opined, presumably based on the “large negro population” of Palestine, Texas, where Seymour taught. The judge’s estimation, based on Seymour’s authorized “study,” worked to confirm the increasingly polarized racial landscape of American culture—it was not that white actors could not look black, it was that they could never reproduce the “essence” that Seymour’s characters had captured.63

More telling, however, was the correspondence that the play generated in the months and years after the Association purchased it from Seymour—for thirty-five dollars—and sold it to the publishing firm of Samuel French. “Lawd, Does You Undahstan’?” was first produced at Paine College in Augusta, Georgia, in 1936, and a year later at Peachtree Christian Church in Atlanta, under the direction of Emma C. W. Gray on both occasions. Joseph T. Lacy, at the time a Paine College student who played the role of Jim, Aunt Doady’s grandson, later recalled positive responses from both the predominantly black audience at Paine and the predominantly white audience at Peachtree.64 But for the Association, the play’s audience was hardly incidental. In response to Elizabeth Morgan’s request for Seymour’s play in January 1937, Ames cautioned that “much of the value of this play is lost if it is not presented before a representative local white group.” Recapitulating the play’s function as a pedagogical tool rather than a performed critique of race relations, Ames continued that “we are so aware of the fact that the lynchers are white people that we try to expose as many of us as possible to educational processes against lynching, and we are almost insistent in our desire to have white people present whenever the play is produced.”65

Thus race figured not only into the representational dynamics of the play—fabricated dialect, mastery of caricature, the idiom of terror for propagandistic viability—but also into practices of reception. Ames understood the racial demographics of the audience to be a critical element in the calculus of the Association’s program of education. At least one other person agreed with her. Reporting on a production of Seymour’s play, Mrs. J. S. Richards, a black woman from Griffin, Georgia, noted that the performance was presented “with so much success” that she had “been asked to repeat it.” Despite the encore, however, Richards “regret[ted] so much that our white friends were not present” and went on to express her “hope to play it” for the local white Woman’s Missionary Society. As though fearful Ames would miss her point, and hinting at the Association’s network of influence, in closing Richards repeated a “cordial invitation to your white friends.”66 Whereas the logics of chivalry masked the operation of race, Seymour’s antilynching play seems to mute the gendered work performed in its spectacle of race. Both venues, however, demonstrate that meanings of race and gender within the discourse and ethos of the Association were anything but independent.

This Barbarous Practice

The horrific practice of lynching is an unsettling fact of the nation’s history. Hardly limited to the American South, the women who organized into the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching nevertheless identified the national epidemic as a problem with a uniquely southern solution. Dismissing academic and constitutional delineations between “religion” and “state,” between theological and civic imperatives, these women transformed their positions of limited recognized power—in churches, in legislative procedure, in the press—into vehicles of political critique and efficacious lament. “We the undersigned women,” members pledged, “believe that the crime of lynching undermines all ideals of government and religion which we hold sacred.” But more than that, they recognized that in order to effect the changes they deemed their states and their souls required, they must first excoriate defenses built upon their own complicity in the barbarous pageantry: “We recognize that all lynching will be defended so long as the public generally accepts the assumption that it is for the protection of white women.” While regional in scope, this window into the political and religious lives of mid-twentieth-century American women sheds light on deliberations that resonated on a national stage. The slipperiness between categories of race, religion, and gender that the Association staged remain pivotal to studies of religion as well as to studies of the region.

-

“N.A.A.C.P. Rubin Stacy anti-lynching flier,” Clippings File, James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. For the most extensive study of vernacular photographs of lynching victims in the early twentieth century, see James Allen et al., Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Santa Fe, NM: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000). ↩

-

Punishment for the Crime of Lynching: Hearings on SB 1978, Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, 73rd Congress (1934); S. Rep. No. 340 (1935); “Anti-Lynching Bill Engages Senate in Lengthy Filibuster,” Vassar Miscellany News, May 1, 1935. ↩

-

Part I, Segregation Part II, Anti-Lynching: Hearings on H.J. Res. 75; H.R. 259, 4123, and 11873, day 2, Before the Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives, 66th Congress (1920) (testimony of Frederick Dallinger, Representative in Congress from the State of Massachusetts). ↩

-

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People campaign circular, ca. 1935. Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL) Papers, Reel 4, File 81. Filing the N.A.A.C.P. circular, Ames expressed reluctance to use “pictures of lynchings or prevented lynchings” in the Association’s material, writing that “there just isn’t any need of arousing women emotionally too much.” See, Sarah Morrison to Ames, January 14, 1937, ASWPL Papers, Reel 2, and Ames to Una Roberts Lawrence, March 3, 1937, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 72. ↩

-

“Feeling is Tense,” pamphlet of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, 1938. https://archive.org/details/FeelingIsTense; “Points to Emphasize in Presenting the Movement against the Crime of Lynching,” undated ASWPL whitepaper, ASWPL Papers, reel 4, file 82. ↩

-

Punishment for the Crime of Lynching: Hearing on S. 24, Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, 74th Congress (1935) (testimony of Caroline O’Day, Representative in Congress from the State of New York). O’Day was born in Georgia but had spent most of her adult life in New York. New York State census enumeration, Westchester County, June 1, 1915; United States of America Passport Application, Westchester County, New York, March 30, 1925; US Census enumeration, Rye, Westchester County, New York, April 4, 1940. ↩

-

Punishment for the Crime of Lynching: Hearing on S. 24, Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, 74th Congress (1935) (testimony of Walter White, Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, New York, New York). ↩

-

“Palatial Piedmont Hotel Opens On January 15,” Atlanta Constitution, January 4, 1903. ↩

-

Mitchell F. Ducy, ed., The Commission on Interracial Cooperation and the Association of Women for the Prevention of Lynching Papers, 1930-1942 (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1984), 1; see also George Edmund Haynes, Toward Interracial Cooperation: What Was Said and Done a the First National Interracial Conference (New York: J. J. Little and Ives, 1926). On Alexander, see Wilma Dykeman and James Stokely, Seeds of Southern Change: The Life of Will Alexander (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962). ↩

-

“Resolutions,” Conference of Southern White Women, November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4; Jessie Daniel Ames, Southern Women and Lynching (Atlanta, 1936), unpaginated. The twelve women who signed the initial resolutions included: Mrs. W. C. Winsborough of Louisiana, Woman’s Auxiliary of the Southern Presbyterian Church; Mrs. W. A. Turner of Georgia, Southern Presbyterian Church; Mrs. W. A. Newell of North Carolina, Woman’s Missionary Council of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South; Mrs. J. Morgan Stevens of Mississippi, Superintendent of Christian Social Relations, Mississippi Conference of the M.E. Church, South; Mrs. Ernest Moore of Mississippi, President of Woman’s Missionary Society, North Mississippi Conference of the M.E. Church, South; Mrs. R. L. Harris of Tennessee, President of the Woman’s Missionary Union, Tennessee Baptist Convention; Mrs. Una Roberts Lawrence of Missouri, Chairman of Personal Service, Southern Baptist WMU, and Director of Publicity, Home Mission Board; Louise Young, WMC of the M.E. Church, South, and educator at Scarritt College; Mrs. Maud Palmer Henderson, Superintendent CSR, North Alabama Conference, M.E. Church, South, Mrs. J. H. McCoy of Alabama; Mrs. Buford Boykin of Georgia; and Jessie Daniel Ames of Georgia. Most of these women remained active throughout the decade and many forged strong, intimate friendships with one another. These personal relationships no doubt reinforced their efforts and suggest a fertile opportunity to explore interdenominational conversations among women in the predominantly white Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist southern bodies. ↩

-

Jessie Daniel Ames, “Southern Women Look at Lynching,” Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching pamphlet (February 1937), 10-11. ↩

-

“Points to Emphasize in Presenting the Movement against the Crime of Lynching.” ↩

-

See John Patrick McDowell, The Social Gospel in the South: The Woman’s Home Mission Movement in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, 1886-1939 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982); Stephen R. Prescott, “The Social Gospel and the American South: An Historiographical Appraisal,” Perspectives on the Social Gospel: Papers from the Inaugural Social Gospel Conference at Colgate Rochester Divinity School (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1999), 33-50; Anne Firor Scott, Natural Allies: Women’s Associations in American History (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991). ↩

-

“Points to Emphasize in Presenting the Movement against the Crime of Lynching.” The memo itself is undated but included in a dossier from 1931-1932. ↩

-

A substantial body of literature on “whiteness” has emerged in the last two decades, a portion of which has informed my critical lens. See, for instance: David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class, rev. ed. (London and New York: Verso, 2007 [1991]); Mathew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998); Edward J. Blum, Reforging the White Republic: Race, Religion, and American Nationalism, 1865-1898 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005); Eric L. Goldstein, The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). On the Johnson Act see Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color, 79-90. ↩

-

Langston Hughes first published “Three Songs About Lynching” in the June 1936 issue of Opportunity, the official organ of the National Urban League. See also, The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, ed. Arnold Rampersad (New York: Vintage Classics, Random House, 1995), 649. ↩

-

Ames to Henrietta Roeloffs, April 18, 1935. See also Roelofs telegram to Ames, April 17, 1935. ASWPL Papers, Reel 1, File 8. ↩

-

It is easy to lose sight of the brutality of lynching when wading through the minutia of bureaucratic correspondence, and perhaps the women themselves distanced the violence of lynching during seasons of relative quietude. But that is doubtful. Unlike the displaced violence of an Abu Ghraib or a Guantanamo, lynchings were a local “barbarism.” “Tokens” of victims were pocketed and brought into the homes of neighbors; familiar trees became monuments to the victory of “anarchy” over “America’s most sacred institutions”; the stench of charred flesh assaulted one’s nostrils and photographic “trophies” were circulated through the post office, permanent records of the brutality. In this article I do not address the actual practice of lynching for one primary reason: the ethics of representation preclude a gloss treatment of the victims. Far too often, lynchings are used as narrative props. This spectacularization works to caricature both the victim and (most often) his assailants. Rather than participate in this perpetual cycle of violence, I have omitted this critical component of the analysis. For studies of lynching in America, see, for instance: James Elbert Cutler, Lynch-Law: An Investigation into the History of Lynching in the United States (London and Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1905); Ida B. Wells-Barnett, On Lynchings, Southern Horrors, A Red Record, Mob Rule in New Orleans, reprint (New York: Arno Press and the New York Times, 1969); Robert L. Zangrando, The N.A.A.C.P. Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980); James H. Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (New York: Palgrave, St. Martin’s Press, 2001); Michael J. Pfeifer, Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874-1947 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004); John Hammond Moore, Carnival of Blood: Dueling, Lynching, and Murder in South Carolina, 1880-1920 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006). For a helpful historiographical review see W. Fitzhugh Brundage, “Conclusion: Reflections on Lynching Scholarship,” American Nineteenth Century History, vol. 6 (September 2005), 401-14. ↩

-

Riddick to Jessie Daniel Ames, February 5, 1931, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4. ↩

-

For the first five years of the Association, the Central Council of the Association—a body composed of Ames (the Executive Director), representatives of “South-wide” religious and civic organizations, and a “minimum of three women fore each of the Southern States”—met in January to recap the previous year and regroup for the year ahead. In 1936 this Central Council meeting was abandoned for a variety of reasons and instead only representatives from States in which lynchings had occurred in 1935 convened. See “Minutes,” January 13, 1936, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4; “Technique for Carrying On the Work,” undated, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, 75. ↩

-

Una Roberts Lawrence to Louise Young, October 15, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. “Points to Emphasize in Presenting the Movement against the Crime of Lynching,” ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 82. ↩

-

McGaughey to Ames, December 3, 1937, ASWPL Papers, Reel 2. ↩

-

Ames, “Minutes,” ASWPL Meeting, January 13, 1936, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4. ↩

-

Ames form-letter to unidentified recipient, January 23, 1933, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 82. ↩

-

“Report, Jessie Daniel Ames, Executive Director, Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching,” January 10, 1935, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 61. ↩

-

Hall mentions that Ida Weis Friend, president of the National Council of Jewish Women, and Rebecca Mathis Gershon, president of the Council’s Southern Interstate Conference, “led Jewish women in strongly backing both the ASWPL and the interracial movement as a whole,” although she does not proceed to expand on their involvement. Thus Jewish women’s participation is an element of the Association that has been greatly unexplored. See Hall, Revolt Against Chivalry, 178. ↩

-

“Standards for 1933,” Minutes, November 18-19, 1932, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 59. ↩

-

Lawrence, Minutes of the Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women, November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

Ames to Young, October 17, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

Accountability was, in fact, a pervasive subtext throughout the Association’s existence. In the midst of Congressional debate over the Costigan-Wagner federal antilynching bill in 1935, for instance, the Association repeatedly encouraged letter writing to members’ Senators and Representatives rather than the authors of the bill or its chief antagonists. On a more local level, it was the responsibility of local members of the Association to secure pledges from municipal and county law enforcement officers, to present the Association’s literature and the “facts about lynching” to their neighbors, and to provide “full investigations” of lynchings if and when they occurred. Local women were also mobilized to investigate the authors of anonymous letters sent to the Association’s central office in Atlanta. ↩

-

Mills to Ames, March 4, 1934, ASWPL Papers, Reel 1, File 8. ↩

-

Ames, Minutes of the Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women, November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

Matthew 25: 42-46 reads: “[42] For I was an hungred, and ye gave me no meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink: [43] I was a stranger, and ye took me not in: naked, and ye clothed me not: sick, and in prison, and ye visited me not. [44] Then shall they also answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, or athirst, or a stranger, or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not minister unto thee? [45] Then shall he answer them, saying, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these, ye did it not to me. [46] And these shall go away into everlasting punishment: but the righteous into life eternal.” See, “Bible: King James Version,” University of Michigan Digital Library Production Service, (accessed April 8, 2014), http://quod.lib.umich.edu/ cgi/k/kjv/kjv-idx?type=DIV1&byte=4380943. ↩

-

Moton, Minutes of the Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women, November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“Feeling is Tense,” pamphlet of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, 1938. https://archive.org/details/FeelingIsTense. Statistics in this pamphlet were drawn from the Tuskegee Institute’s 1937 Negro Yearbook. ↩

-

On Jennie Moton see, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, “Jennie B. Moton,” Robert Russa Moton of Hampton and Tuskegee, ed. William Hardin Hughes and Frederick D. Patterson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956), 204-206. Robert Russa Moton was largely responsible for acquiring the funding to underwrite the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, and thus the Motons remained closely affiliated with the Association and became intimate friends with Ames. See Hughes and Patterson, Robert Russa Moton, vi. ↩

-

“Standards for 1933,” Minutes of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching 1932, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 82. ↩

-

“Minutes,” January 10, 1935, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4. The seeming indifference of Baptist churchwomen would trouble Ames throughout the decade. In a letter to Laura Dell (“Mrs. F. W.”) Armstrong in September 1939, she wrote: “Of course you know that for quite sometime I have felt concerned over the failure to enlist the sympathetic cooperation of the Baptist women in our program of education against lynching.” See Ames to Armstrong, September 14, 1939, ASWPL Papers, Reel 2. ↩

-

In 1910 the Foreign Mission and Home Mission Boards of the denomination were merged into the Woman’s Missionary Council, which remained in effect until the Southern and Northern branches of the Methodist Episcopal Church reunited in 1939. McDowell locates the beginning of organized “race-relations” among Southern Methodist women at a Memphis conference in October 1920 funded in part by the Commission on Interracial Cooperation. See McDowell, The Social Gospel in the South, 89-115. ↩

-

Louise Young, interviewed by Jacquelyn Hall and Bob Hall, February 14, 1972, Interview G-0006, Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, (accessed online March 14, 2008, http://docsouth.unc.edu/ sohp/G-0066/G-0066.html). ↩

-

Southern Baptists also had a tradition of race relations reaching back into the antebellum period, but differed from Methodists in efforts to mobilize for social action. See Paul Harvey, Redeeming the South: Religious Cultures and Racial Identities among Southern Baptists, 1865-1925 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997). ↩

-

White, Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch, reprint (Salem, New Hampshire: Ayer Company, 1992 [1929]). ↩

-

Lewis, When Harlem Was in Vogue (New York: Penguin Books, 1997 [1979]), 205. ↩

-

“Minutes,” Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women, November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

“Minutes,” ASWPL Annual Meeting, January 13, 1936, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 62. ↩

-

Armstrong, “Moral Standards,” Royal Service 34 (September 1939), 4, ASWPL Papers, Reel 2, File 10. ↩

-

“W. M. U. Speaker for Enforcement, Richmond [Virginia?] News Leader, May 12, 1932, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 72. ↩

-

“Report,” January 10, 1935, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 61. ↩

-

Morrison to Ames, November 17, 1936. Morrison edited the Record of the Girls’ Friendly Society of the United States of America. ↩

-

Ames to Morrison, November 24, 1936, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 74. ↩

-

Craig Prentiss has demonstrated how sacred texts and ecclesial offices “shape” notions of race by articulating and enforcing interpretive traditions. While this thesis is sound, it is equally true that the notions of race mobilized by religious groups to navigate terrestrial and celestial landscapes are the products of habits of perception and recognition; in this way, authorizations extending from ecclesial offices are entangled in common processes of signification. The very currency of official discourses of race is contingent on practices of perception, which take place in the quotidian habits of lived experience. Thus while ministers and theologians might search the bible or ecclesial tradition for insights into the meanings inscribed on human flesh, understanding habits of recognition demand we pay attention to the practices that authorize, veto, or revise authoritative discourses of race. Prentiss, “‘Loathsome unto Thy People,’: The Latter-day Saints and Racial Categorization,” Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction, ed. Craig R. Prentiss (New York: New York University Press, 2003), 124-39. ↩

-

Wells, A Red Record (Chicago, 1894; repr., New York: Arno Press and the New York Times), 12; “Resolutions,” November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4; “Mrs. O’Bear,” Minutes of the Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women, November 1, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

“Southern Association of Women for the Prevention of Lynching [pledge form],” undated, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 75. Ames wrote to Senator John H. Bankhead that “we feel strongly that our honor cannot be used to add a halo of chivalry to acts which grow out of conflicts between men without reference to women.” Ames to Bankhead, April 25, 1935, ASWPL Papers, Reel 1. ↩

-

The purpose of this document was to furnish speakers with an argument for the “homogeneity” of the South in order to garner the attention of Southerners who might otherwise dismiss lynching as the actions of either the deranged or the destitute. It has the additional effect, however, of demonstrating that whiteness was a racialized category no less than blackness. “Suggested Points in Presenting Purpose of A.S.W.P.L.,” undated, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 75. ↩

-

See, for instance, entries for “Caucasian,” “white,” and “Anglo-Saxon” in the Century Dictionary (1889-91), and Funk and Wagnells (1935). For two cogent analyses of “whiteness[es]” in American history that touch on religious discourse, see: Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color, and Blum, Reforging the White Republic. Jacobson’s study covers the period here examined, although Blum makes a stronger argument for the role that religious discourse played in the articulation of a “white republic.” Of course chivalry freights a thoroughly gendered logic as well. My aim here, however, is to tease out the equally informative racialized logics that have hitherto largely been eclipsed by gendered readings. ↩

-

“Appendix F: Report of Mississippi Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching,” Minutes of the Central Council, 1931, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4. ↩

-

Cook to Sullens, May 25, 1937; Greeson to Ames, June 25, 1937; Greeson to Ames, July 2, 1937; Ames to Greeson, July 6, 1937, ASWPL Papers, Reel 1. ↩

-

“Minutes” of the Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57; Telegram to Alice Ames Winter, November 3, 1930, ASWPL Papers, Reel 3, File 57. ↩

-

“Suggested Checklist for Plays Against Lynching,” ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 71. ↩

-

“Report of Judges on One-Act Plays,” and “One Act Play: Lawd, Does You Undahstan’?,” ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 71. Seymour’s play was printed in Representative One-Act Plays by American Authors, ed. Margaret Mayorga, rev. ed. (Boston, 1937), and more recently in Strange Fruit: Plays on Lynching by American Women, ed. Kathy A. Perkins and Judith L. Stephens (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1998). ↩

-

Ames quoted in Perkins and Stephens, ed., Strange Fruit, 189. ↩

-

“Report of Judges on One-Act Plays,” ASWPL Papers, Reel 4, File 72; Mayorga, Representative One-Act Plays, 521. ↩

-

Mayorga, Representative One-Act Plays by American Authors, 524; Perkins and Stephens, Strange Fruit, 189-90. ↩

-

Morgan to Ames, January 26, 1937; Ames to Morgan, January 27, 1937, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4. ↩

-

T. [?] S. Richards to Ames, February 11, 1937, ASWPL Papers, Reel 4. ↩