From Prizefights to Praying Colonels: Civil Religion, Sports, and a New(ish) Direction for the Lost Cause

“His Courage as White as His Skin is Black,” declared a headline in the July 5, 1910 Richmond Times Dispatch, referencing a prizefight one day earlier in Reno, Nevada, between Jack Johnson and Jim Jeffries.1 Johnson had become the first black man to win boxing’s heavyweight title by defeating Tommy Burns in 1908.

Jefferies, meanwhile, had retired in 1905 with an aura of manly mystique that had made him a living legend. While he initially resisted the calls to return to the ring to vanquish Johnson, Jeffries’s dwindling finances as well as the collective will of his supporters drew him back. As the “Fight of the Century” drew near, white fans in particular imagined it as both a battle for racial supremacy and for the fate of the nation. On the day of the fight, the Daily Picayune in New Orleans printed a cartoon of a fit, slim, and athletic Uncle Sam sparring in a boxing ring, with an eagle overseeing his training.2 Whiteness and Americanness unified through the sport.

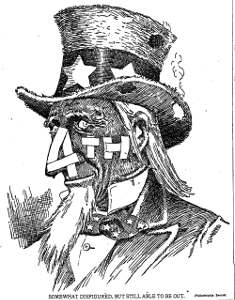

Alas, the actual match, however, was profoundly anticlimactic. Johnson dominated Jeffries, who fell unceremoniously after fifteen rounds.3 The Daily Picayune featured another image of Uncle Sam, his humble visage bruised, bandaged, and beaten.4

And in Richmond, as previously mentioned, a newspaper tactically bleached Johnson’s courage, perhaps also in an effort to soothe the city’s bruised white ego. But after the headline, the Richmond newspaper had little good to say about the match or prizefighting, casting it as a loathsome affair, irredeemably flawed for its culture of brutality, gambling, and debauchery. The slicing words cut deeper as the author addressed the accounts of riots breaking out in American cities in the fight’s aftermath. With irony and sarcasm hanging from the prose, the author assured readers that these disruptions had happened “in the Northern part of the great Christian country” where “the sainted members of race equality live.” In the South, the author continued, racial unrest was isolated to places like Atlanta, “the heart of the New South . . . [which is] more like a Northern town than any town in these parts.” Indeed, in Richmond—“the soul” of the Old South—and in similar sites, the author claimed that there was no racial unrest, since southerners had a firm handle on the “race problem.”5

In the eyes of one Richmond newsman, the Johnson-Jeffries fight became a morality tale about race, region, and social stability. Significantly, he punctuated his ethical analysis with Lost Cause rhetoric that contrasted an Old South of racial harmony and refined manners, with a North and New South of disorder and chaos.

As Charles Reagan Wilson has eloquently and sufficiently demonstrated, the Lost Cause was far more than hulking statues and nostalgic speeches. Rather, this movement had a distinct civil religious dimension, as sacred stories, powerful symbols, and unifying rituals translated into a coherent set of white southern beliefs and values.6 Wilson’s insights remain highly influential, appearing in monographs, encyclopedias, and even a PBS film documentary.7 As a result, any mention of “civil religion” in proximity to the postwar South seems to inevitably lead us to the Lost Cause.

In my own work, I have endeavored to stretch the connective tissue that brings these two categories together.8 Specifically, I have situated the Lost Cause as one civil religious discourse among many. Blacks, whites, men, women, progressives, northerners, Catholics, Protestants, and Jews all lived in the South, and all developed social values that they believed transcended individual interests and contributed to the common good. Some groups had more political influence, economic strength, or numbers than others did. Still, the politically disfranchised, the economically alienated, and the numerically diminutive had the will and imagination necessary to envision on their own terms what society ought to be.

To develop this methodology, I followed the lead of civil religion scholars who have reconceived the category to cast a wider net, to account for a broader range of perspectives. For better or worse, Robert Bellah’s infamous 1967 article on the topic launched a discussion on the religious characteristics of the “American way of life.” The scholarship that followed tended to think in singular terms—asking questions about what “we” hold in common. Nearly two decades after Bellah’s article, though, sociologists N. J. Demerath and Rhys Williams put forth a challenge to scholars to investigate “the contexts and uses of civil-religious language and symbols, noting how specific groups and subcultures use versions of civil religion to frame, articulate, and legitimate their own particular political or moral visions.”9 Demerath and Williams triggered a new wave of scholarship that pivoted away from the colonized land of consensus, and directly in to the unmarked territory of difference, competition, and conflict.10

Returning to the Johnson-Jeffries fight, I see yet another place to build upon the conversation started by Professor Wilson. In the same years that southerners were developing a sports culture, the Lost Cause had become an ambient part of the region’s rhetorical composition, shaping not only the United Daughters of the Confederacy, but also the moral interpretations of everyday events. And so, the Richmond Times Dispatch leveled opinions on the Johnson-Jeffries fight with a nod to the Old South, a genuflection to the altar of white supremacy, and an assault on the North and New South.

But Jack Johnson meant different things to different people, especially to his supporters—both black and white. Their voices issued a force that pressed against the Lost Cause, as each discourse intentionally and unintentionally shaped each other. Consider the Richmond Planet—a black newspaper. In reporting on the Johnson-Jeffries fight, the lead editorial expressed a measured degree of jubilation at the outcome, alongside a favorable depiction of the champion’s demeanor. “Johnson made many friends as a result of his fairness,” the author emphasized. “He showed…that he had many of the characteristics of the Southern colored man by his modesty, when victory was assured.” As for the riots, the author dismissed these reports as “the work of the politicians,” while pointing to Richmond, where “friendly feelings” continued between the races. In final analysis, he wrote, Johnson was “a God-sent blessing” who had shown that blacks were “one of the most powerful races of people on the face of the globe.”11

This editorial represented not only a black response to Johnson’s victory, but also a civil religious discourse anchored in a history of slavery, emancipation, and a struggle for freedom. Of course, the voices of blacks in the South were as varied as any other group. Critics of Johnson denounced his flagrant disregard for racial barriers, and others dismissed the entire endeavor of prizefighting. Still, these black civil religious discourses existed alongside, and in competition with, many other voices of the South.

In what remains, I offer additional dispatches from the Johnson-Jeffries fight, before turning briefly to other sports in this era. My hope is to propose a “new direction” for the Lost Cause that both recognizes its significance, and integrates it into a decentered story of the South in all of its variety and complexity.

When the Johnson-Jeffries match approached, a New Orleans sportswriter celebrated the fight and the fighters by depicting them as models of clean living and “careful self-denial.” As to the violence, the author rebutted: “[N]otwithstanding what moralists will and should say, the fact remains that the English-speaking race dearly loves a brutal fight, especially where there is every guarantee of fair play and an exhibition of nerve, skill and physical endurance.” And on the fight’s racial implications, the author was unconcerned. In the prize ring, he averred, “a negro is regarded as the equal and even the superior of the white man.”12

With sentiments like these emerging from southern prizefighting enthusiasts, it is of little surprise that someone like Anne Riley Hale had such a dim view of the sport. Hale was a noted conservative writer from Rogersville, Tennessee, with a penchant for employing Lost Cause nostalgia in her social commentaries. To denounce the Johnson-Jeffries fight, she began by recounting the standards for dueling in the Old South. A gentleman, she assured, would never do combat with “a social inferior.” Yet “the knights of the prize ring” had abandoned “the niceties of social distinctions.” In Hale’s mind, the negative consequence of this revolution in manners could not have been more socially harmful. The riots in the North were, for her, proof that in places where the “color-line” had become blurred, racial violence was inevitable. She called upon the nation to follow the lead of “thoughtful Southerners,” and make segregation the law of the entire land.13

Not surprisingly, Hale failed to mention the violence that had erupted in southern cities after the fight. And the actions of southern legislators only further betrayed her conclusion that segregation protected the social order. In Richmond, city council members quickly drafted a resolution to ban fight films, which they assumed would “excite race prejudice and cause disorder and violence.” Atlanta, Lexington, Savannah, and many other cities did the same.14 Eventually, the issue became a matter of federal concern. U.S. Representative Seaborne A. Roddenberry of Thomasville, Georgia, proposed federal legislation that would limit interstate shipment of the fight films.15 And when Johnson married a white woman, Lucille Cameron, Roddenberry continued his campaign against the boxer, proposing a constitutional ban on interracial marriage. “It is destructive to moral supremacy,” he thundered, “and ultimately this slavery of white women to black beasts will bring this nation a conflict as fatal and as bloody as ever reddened the soil of Virginia or crimsoned the mountain paths of Pennsylvania.”16

For Roddenberry, Jack Johnson’s athletic prowess and white spouse symbolized an extreme act of transgression, one that the white politician used to mobilize legal forces in his favor.17 Elsewhere in the South, more extreme politicians skipped legislative solutions in favor of lawlessness. When news of Johnson’s marriage broke at a governor’s meeting in Richmond, Governor Cole Blease of South Carolina informed the gathering that if Johnson came south, he would be lynched. Fellow governors asked Blease if he would uphold the constitution and defend Johnson. “To hell with the Constitution!” Blease bellowed. “When the Constitution steps between me and the defense of the virtue of white women of my state,” the governor elaborated, “I will resign my commission and tear it up and throw it to the breezes.”18

Blease’s stout opposition to Johnson’s very existence bundled racial pride, gender purity, and southern exceptionalism—a potent mix that was the lifeblood of the Lost Cause. As examples like this would indicate, in these tender years of the twentieth century the Lost Cause often appeared as a foil to sports, athletes, and athletics. This was not, however, a hard rule. In some instances, the games that people played became an extension of regional identity. And as sports continued to enchant the imaginations of white southerners, the Lost Cause would find even more positive expressions in in the South’s sports culture.19

Baseball took root in the South shortly after the Civil War, and was arguably just as popular as prizefighting in the coming years. “The number of persons afflicted with ‘baseball on the brain’ is rapidly increasing,” proclaimed one Memphis newspaper in 1867. The author documented the flood of new club teams forming, all of them “anxious to secure to themselves the amusement of the healthful recreation imparted by this fine exercise.”20 In Memphis and elsewhere, the names of these clubs bore regional distinction, as teams named “Stonewall Jackson” could very well play against “The Pride of the South.”21 In New Orleans, popular clubs assumed names like, “Robert E. Lee,” “Lone Star,” and the “Southerners.” In 1869, members of the latter club toured the nation, winning six of seven games. The traveling team’s triumph, according to one account, gave “a new impulse to base ball in our city.”22

In these initial years, baseball was both a national game and an opportunity to display and celebrate “southern” identity within the region and beyond. As the game became more popular, baseball—like prizefighting—became a source of moral disputes. Football followed a similar trajectory, especially on college campuses. Trinity College (now Duke) started a program in 1887, to the delight and amusement of their student body. By 1895, however, after years of controversy, the school’s new president shut the program down, labeling football “an evil that the best tastes of the public have rebelled against.”23 Other southern schools with religious affiliations followed suit. Yet, by the 1920s, college football had a renewed appeal at these same schools, with intersectional contests attracting great interest.

In 1921, the “Praying Colonels” of Centre College in Kentucky traveled north to take on the mighty Harvard Crimson. The relatively unknown school from the bluegrass state won 6–0, behind the leadership of quarterback Bo McMillin. While teams like Vanderbilt and Auburn had experienced some success in interregional contests, Harvard was a perennial powerhouse that had routinely dismantled southern squads. So the news of Centre’s victory was met with pride and pleasure throughout the South. The front page of the Atlanta Constitution announced: “Centre Saves South,” as they dubbed McMillin a “New Immortal.”24

Centre’s chaplain would capitalize on this celebrity by telling the story of these “pious” southern athletes on the revival trail. And when Trinity reconstituted its football program, they intentionally adopted the combination of playing and praying modeled by the Centre stars.25 Other interregional contests in this decade and beyond would bring “the South” into tighter alignment with faith and football. When Alabama won the 1926 Rose Bowl, one journalist called the 20-19 victory a “blessed event.” For their part, the university would enshrine this triumph in their fight song, which thereafter ended with the line, “You’re Dixie’s football pride, Crimson Tide!”26

To conclude, if I were to write a history of religion and sports in the New South, it would not be directly concerned with the Lost Cause. The sports culture of this era, after all, was a microcosm of New South ideology—notably connected to the North, nation, and world; urbane; incorporated; progressive; modern; and imbued with forward-thinking optimism. That said, when examining this era, it’s hard to avoid the Lost Cause. To adapt a tired truism, the Lost Cause was both everywhere and nowhere. And so, from prizefights to the Praying Colonels, the sports culture of the New South has a potential for showing us new ways of conceptualizing the Lost Cause. There is, to be sure, plenty of work to be done on focused studies of this movement—that is, examinations of statues, speeches, Confederate organizations, and the like. At the same time, I also see a value in mapping out the exteriors of the Lost Cause, and following the traces of this civil religious discourse to wherever it leads us.

The editors wish to thank Art Remillard for organizing and editing this forum on southern civil religions.

-

“His Courage as White as His Skin is Black,” Richmond Times Dispatch, July 5, 1910. ↩

-

Daily Picayune, July 4, 1910. ↩

-

For an excellent recent biography of Johnson, see: Theresa Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). ↩

-

Daily Picayune, July 5, 1910. ↩

-

“His Courage as White as His Skin is Black.” ↩

-

Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980). ↩

-

Llewellyn Smith, et.al. Reconstruction: The Second Civil War (PBS, 2004). ↩

-

Arthur Remillard, Southern Civil Religions: Imagining the Good Society in the Post-Reconstruction Era (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011). See also, Arthur Remillard, “Reflections on Southern Civil Religions; or, Confessions of an Academic Carpetbagger,” Journal of Southern Religion 16 (2014): http://jsreligion.org/issues/vol16/remilard.html. ↩

-

N. J. Demerath and Rhys Williams, “Civil Religion in an Uncivil Society,” Annals of the American Academy 480 (July, 1985): 166. ↩

-

See, for example, Jonathan S. Woocher, Sacred Survival: The Civil Religion of American Jews (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); Rita Kirk Whillock, “Dream Believers: The Unifying Visions and Competing Values of Adherents to American Civil Religion,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 24, no. 2 (1994); Marcella Cristi, From Civil Religion to Political Religion: The Intersection of Culture, Religion and Politics (Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001); David Krueger, Myths of the Runestone: Viking Martyrs and the Birthplace of America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Anne M. Blakenship, “Civil Religious Dissent: Patriotism and Resistance in a Japanese American Incarceration Camp,” Material Religion 10, no. 3 (2014); Carole Lynn Stewart, Strange Jeremiahs: Civil Religion and the Literary Imaginations of Jonathan Edwards, Herman Mellville, and W. E. B. DuBois (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011). ↩

-

“Great Fight in Nevada,” Richmond Planet, July 09, 1910. ↩

-

“The Coming Fistic Battle,” Daily Picayune, July 3, 1910. ↩

-

Annie Riley Hale, “The Lesson of the Black-and-White Prize-Ring,” Macon Daily Telegraph, July 12, 1910. On Hale, see Elna C. Green, Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 106. ↩

-

“Fight Pictures Can’t Come Here,” Richmond Times Dispatch, July 07, 1910. ↩

-

Quoted in Geoffrey C. Ward, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 283. ↩

-

Quoted in Ward, Unforgivable Blackness, 322. ↩

-

“Jack Johnson Wedding Denounced in Congress,” New York Tribune, December 12, 1912. ↩

-

“Governors Rebuke Mob-Law Blease for his Doctrine,” Daily Picayune, December 7, 1912. ↩

-

Arthur Remillard, “Between Faith and Fistic Battles: Moralists, Enthusiasts, and the Idea of Jack Johnson in the New South,” Perspectives in Religious Studies 39, no. 3 (2012). ↩

-

“Base Ball,” Memphis Daily Appeal, May 25, 1867. ↩

-

“Another Base Ball Match Yesterday,” Memphis Daily Appeal, May 30, 1867. ↩

-

“Welcome to the Southerners,” Daily Picayune, August 29, 1869; Peter Morris et al., Base Ball Pioneers, 1850-1870: The Clubs and Players Who Spread the Sport Nationwide (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 308. ↩

-

William J. Baker, Playing with God: Religion and Modern Sport (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 102. ↩

-

“Centre Saves South,” Atlanta Constitution, October 30, 1921. ↩

-

“Center College Man Makes Talk on Faith,” Tar Heel, March 17, 1922; “Football Starts at Trinity ‘Hit Trail’ At Revival,” Atlanta Constitution, December 4, 1921 ↩

-

Eric Bain-Selbo, Game Day and God: Football, Faith, and Politics in the American South (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009), 140-41. ↩