A Misplaced Hope:

Howard Kester, the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen, and the Failed Attempt to Mobilize White Moderate Protestants in Support of Desegregation, 1952-1957

Peter Slade

Professor of Religion at Ashland University.

Cite this Article

Peter Slade, "A Misplaced Hope: Howard Kester, the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen, and the Failed Attempt to Mobilize White Moderate Protestants in Support of Desegregation, 1952-1957," Journal of Southern Religion (20) (2018): jsreligion.org/vol20/slade.

Open-access license

This work is licensed CC-BY. You are encouraged to make free use of this publication.

“Cry aloud for righteousness the Church must or lose its own soul . . . That the Church fail not in her divine task is our hope and our prayer. Amen.”1 - Thomas “Scotty” Cowan, 1955.

“What is at stake is a great deal more than the integration of the public schools: a whole new way of life must be found and built . . . it cannot be done by force, violence and hysteria . . . Unless a way is found . . . the present situation will undoubtedly worsen and as it worsens decades may be required to heal the wounds of children yet unborn.”2 - Howard “Buck” Kester, 1956

“Hope deferred maketh the heart sick.” - Proverbs 13:12

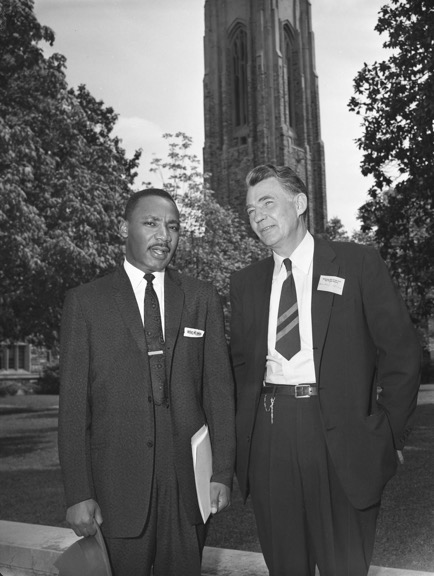

On April 25, 1957, the Nashville Banner printed a photograph of two ministers. One is black and one is white, one is young and one is middle-aged. The caption informed readers that “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr . . . [the] minister who started the now-famous bus boycott in Montgomery last year” stands to the right of “Howard Kester, executive secretary of The Fellowship of Southern Churchmen.”3 King looks directly into the camera as he talks; the older white man, Kester, age 53, listens with head cocked. Looming behind them is the gothic stone tower of Scarritt College, symbolizing the power and prestige of white denominational Christianity.

Kester was the organizer of the three-day Conference on Christian Faith and Human Relations, which was the occasion for the photograph and the reason for King’s presence in Nashville. The photograph was taken right before King addressed a group of around 300 mostly white clergy and seminarians from across the South. He told them they needed to be “as maladjusted as Jesus who dared to dream a dream of the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of men. The world is in desperate need of such maladjustment.”4 Certainly King and Kester were maladjusted men of their day. On that particular day, they were united in a hope that they could rally the well-meaning, liberally educated clergy of the white Protestant churches of the region to persuade, influence, and educate their congregations to allow the peaceful integration of public schools and the dismantling of Jim Crow. “It is my profound hope that more leadership will come from the moderates in the white south,” King told the conference, “God grant that the white moderates of the south will rise up courageously, without fear, and take over the leadership of the south in this tense period of transition. The nation is looking to the white ministers of the south for much of this leadership.”5

A couple of months earlier, Kester had expressed a similar hope coupled with a belief that the Conference on Christian Faith and Human Relations would be significant in launching a Christian movement that would politically transform the region. “This is the sort of meeting of Christian minds and hearts at a moment of profound crisis for which the Fellowship was born and now exists,” Kester wrote in the Fellowship’s newsletter in January. “It could be a meeting of the grassroots and the summit for which we have been working all these years, and it could very well represent the turning point in the churches’ effective grappling with and witnessing for a magnificent solidarity of the human family within the body of Christ.”6 Working from the National Council of Churches office in Nashville, the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen (FSC) mailed out over 4,500 invitations to Protestant clergy across the South: only 300 came to the conference.7

The changing of the “maladjusted” guard. Martin Luther King Jr. and Howard Kester at the Conference on Christian Faith and Human Relations, Scarritt College, Nashville, April 25, 1957. Photographer: Jack Gunter, courtesy Nashville Public Library, Special Collections.

With the benefit of hindsight, this posed newspaper photograph is poignant. It marks a chimeric highpoint of the liberal hope that white southern Christians would be a significant force in bringing racial reform and reconciliation to the region. At the time, even as he stood next to the newly famous civil rights leader, Kester must have realized that his plan had failed. For Kester, this conference was the culmination of twenty-three years of work with the interracial band of self-styled radical prophets of the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen, but it was also his swansong. He quit the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen following the conference and the Fellowship effectively ceased to function. Over the next six years, King’s hope in white moderates and liberal clergy turned famously sour. “I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate,” he wrote from his cell in Birmingham in 1963. “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate.”8

This article is an examination of the work of Howard Kester and the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen during the critical years 1952–1957, the years surrounding the Brown decision when the South could have peacefully accepted the decision of the Supreme Court. It considers the development of the FSC’s strategy to organize white clergy in the hope of influencing the moderate members of their congregations to help their communities embrace the integration of public schools and the dismantling of Jim Crow. This article sets Kester and the FSC’s efforts in the context of the rise of Massive Resistance and the maintenance of segregation by the white Protestant churches in the South, making it a part of the long story of the movement for civil rights in America and the far longer narrative of the symbiotic relationship between white supremacy and Christianity. For an all-too-brief moment, there was a genuine and strategic internal struggle in those southern Protestant congregations between social progressives and anti-integrationists for the hearts and minds of the average “moderate” churchgoer. Howard Kester and the FSC rightly understood themselves to be in a battle with anti-integrationist forces over these white churchgoing moderates: the FSC wanted to unite them in action, the Citizens’ Councils wanted to intimidate them into inaction. This article fleshes out a crucial, though anticlimactic, chapter in the history of the FSC and the biography of Howard Kester, which has received little attention from historians.9 It also contributes to a growing body of scholarship examining the role of white churches during the civil rights movement.10 This study of Kester and the FSC adds to that corpus a detailed inspection of how, at the birth of the civil rights movement, an established interracial group of progressive southern Protestants understood the challenges facing their churches and their region.

The South was the theater for a long-running religious drama. “The era from the Civil War to the civil rights movement,” as Paul Harvey suggests, “might be described for the South as God’s long century, for it was in the South during this time that American Christianity was at its most tragic and most triumphant.”11 The FSC (as an organization) and Howard Kester (as an organizer) were present for at least two acts of this drama: the interwar years with their labor disputes, depression, and the New Deal; and the 1940s and 50s with the rise of the Dixiecrats, the expansion of the NAACP, the Brown decision, boycotts, and school desegregation. Bowing out just before the student sit-ins, nonviolent direct action, marches, and civil rights legislation, meant that the FSC and Kester experienced plenty of the tragedy and little of the triumph. The maverick preacher Will Campbell believed this timing made his friend, Howard Kester, “a tragic figure in a way.” In leaving the stage when he did, Campbell said of Kester, “I didn’t consider that he was defeated by the world’s standards, [but] he never won a battle.”12

To examine the work of Kester and the FSC in the 1950s it is necessary to consider the tradition of radical southern Protestant Christianity and its understanding of race in the earlier act. Only then is it possible to appreciate the actions of the Fellowship and the inaction of the moderates it hoped to influence in the post-war period.

Howard Kester & the Radical Roots of the FSC

The YMCA was the single most significant influence on Howard Kester’s religious vocation and his understanding of race, as it was for a generation of religiously motivated social reformers in the South.13 Born in 1904 to Presbyterian parents, Kester grew up in the tobacco fields and farms of Martinsville, Virginia, where he learned the social etiquette of benevolent paternalism and white supremacy. When Kester was a teenager, the family moved to the coalfields of Beckley, West Virginia, where he saw the poverty of miners and their strikes for better pay and conditions. From 1921–1925 at Lynchburg College, as a student on a ministerial scholarship, he came into contact with the “Y.” Until then his religious instruction had been the standard evangelical theology of the Southern Presbyterian Church, and the straightforward Protestant piety of personal prayer and adherence to the Golden Rule instilled in him by his mother. College exposed him to the progressive social gospel, pacifism, and inter-racialism of the interwar YMCA.14 The YMCA employed Kester while he was still a student and, though it was a rigidly segregated organization in the 1920s, its African American leaders exerted a strong influence on the young Kester.15 Rejecting any shred of gradualism or equivocation when it came to the sinfulness of segregation, Kester regularly disregarded laws and conventions concerning separate public accommodation for whites and blacks.16 This, it is important to recognize, put him at odds with the Southern liberal whites of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC) and the white YMCA leadership. From 1926 until 1934, Kester was busy with student and labor organizing, working first for the YMCA, and then, when they sacked him for his socialist politics and insistence on holding interracial meetings, the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). His humility, empathy, and insight in matters of race set him apart from his peers. African American leaders of the day recognized and valued him. The executive secretary of the NAACP, Walter White, writing in 1934, described Kester as “a first-rate young white man, who is absolutely right on the race question.”17 Kester counted George Washington Carver, James Weldon Johnson, and sociologists Charles S. Johnson and E. Franklin Fraser among his teachers and mentors, and Howard Thurman and Benjamin Mays among his friends. It is hard to dispute John Egerton’s claim of Kester that “it would be difficult to name any white Southerner of the time who had more contacts across racial lines than he did, or more of a clear-eyed vision of the crippling effects of segregation on blacks and whites alike.”18

Kester’s clear-eyed view of the evils of segregation came through a Christian socialist lens with a particular southern and agrarian tint. While a student at Vanderbilt’s School of Divinity, he had fallen in with a group of young white seminarians—James Dombrowski, Don West, Claude Williams, and Myles Horton, all students of Alva Taylor at Vanderbilt or Reinhold Niebuhr at Union Theological Seminary in New York—who shared a desire to address the South’s intertwined injustices of racial discrimination and the exploitation of its people’s labor.19 Kester brought his unwavering determination to this group. He was, as Will Campbell remembered, “One of the most stubborn human beings I have ever known.”20

The Fellowship of Southern Churchmen (1934-1951)

In 1934, when his activities became a little more than the leadership of the pacifist FOR could comfortably endorse in their secretary, the socialist theologian Reinhold Niebuhr established the Committee on Economic and Racial Justice (CERJ) for “the support of Howard Kester’s work in the South.”21 That same year, James Dombrowski—a socialist friend, Methodist minister, and administrator of the recently established Highlander Folk School—called a meeting of like-minded ministers from across the South. On May 27, 1934, an interracial group of around forty ministers met in a hotel in Monteagle, Tennessee.22 Reinhold Niebuhr travelled down from New York and held his audience spellbound. Rev Thomas “Scotty” Cowan, the powerful preacher of Third Presbyterian Church, Chattanooga recalled: “Those of us who attended will never forget Niebuhr’s mind-kindling talks, his dialectical skill, his prophetic probing of our social order and the Church.”23

Naming the group “the Conference of Younger Churchmen of the South,” they appointed Howard Kester its executive secretary and Kester’s wife, Alice, the administrative assistant, running the office from their home in Nashville. “Conference” did not capture the close-knit camaraderie embodied by this small group of self-appointed radical social prophets. In 1936, they changed the name to the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen. At the same time, they adopted a statement of principles to which future members would need to subscribe.24

The Fellowship was an intellectual movement: its leaders spent a great deal of time discussing, revising, and expanding its Statement of Principles (the version adopted in 1938 was 10 pages long). Distinguishing the Fellowship from the liberalism of the CIC and the political radicalism of the Socialist and Communist parties was the influence of Reinhold Niebuhr, “the spiritual godfather of the Fellowship.”25 Exactly how Niebuhr’s influence played out in the thought and actions of the Fellowship’s members is complex.26 In the 1930s, Niebuhr was a socialist and employed a Marxist economic analysis. “The collective behavior of men,” Niebuhr insisted, “must be understood on the whole in the light of their economic interests.”27 The FSC shared this analysis and “reject[ed] the idea that the labor of men can be bought and sold as a commodity.”28 At the same time, the FSC embraced Niebuhr’s pessimism when it came to the possibilities of collective human action, which he had clearly laid out in his 1932 classic Moral Man and Immoral Society. In its 1938 “Statement of Principles,” the FSC demonstrated this Niebuhrian rejection of the Communist Party’s atheist eschatology in its “acknowledgement of man’s sinfulness that prevents the equating of any social order old or new with the Kingdom of God on earth. Man is a child of God but he is also a sinner and a more perfect social order, however organized, cannot alone eliminate the evil in his heart.”29 However, Niebuhr’s neo-orthodoxy did not simply sweep all before it; its pessimism tempered, but did not entirely eliminate, the optimism of the YMCA’s social gospel. In 1936, Kester described himself (and by extension, the FSC) “as a religious revolutionary, as a Christian and a left-wing Socialist who believes in the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth.”30 The Kingdom would come when Christians realized “the redemption of the individual and of Society are one and inseparable.”31

To appreciate the strategy adopted by the FSC in the 1950s, it is essential to understand that from its inception the group not only opposed segregation but also conducted all its business with a disregard for, and a defiance of, Jim Crow. The FSC did not wait for the South to legally abandon segregation, its principles clearly stated: “we acknowledge that racial persecution can only be completely abolished as other divisive barriers are removed. But in the meantime we declare our obligation and our joy to live as brothers to men of every race and color.”32

From the writings of FSC members and the extensive oral histories collected in the early 1980s by seminarian-turned-sociologist Dallas Blanchard, it is evident that this commitment to live out its interracial principles “in the meantime” was the dimension of the Fellowship’s work that most impressed its members.33 For many, the FSC was the only venue in which African Americans and whites met on equal terms. Melvin H. Watson, who joined the FSC in 1938 while he was teaching at Morehouse College, described the FSC as “an oasis in a desert land.”34 Henry H. Mitchell, an African American graduate of Union Theological Seminary who came into contact with the FSC while serving as the interim Dean of the Chapel at North Carolina College for Negroes in 1944, was surprised to find that he did not sense the covert racism or paternalism that he often found “in people who see themselves as liberals.”35 What startled Maynard Catchines, roommate of James Farmer at Howard University, was that “there weren’t even cleavages between black male and white female association . . . That didn’t seem to upset anybody in the group.”36

This “meantime” interracial fellowship profoundly influenced the theological imagination of whites. In the 1940s, Emmett Johnson, a professor at Candler School of Theology, involved his students in an FSC-sponsored interracial fellowship with students at Gammon Theological Seminary. Ernest Seckinger, one of the white seminarians, recalled, “I remember taking the Lord’s Supper, kneeling between two blacks, and you know, we didn’t have any particular line up, but could remember how natural and normal and how right that seemed.” Seckinger confessed that, “It was the first experience I had . . . [of] really thinking of blacks as people.”37

Away from the interracial oases of the Fellowship’s meetings the members saw themselves as God’s prophets—isolated Protestant Elijahs scattered from Texas to Virginia, a region with churches that had “bowed the knee to Baal.”38 Judging from its literature, the FSC of the 1930s understood its most important function was to be a support group, reminding its members that even if they often felt so, they were not alone in the struggle.

There was an important thread in Kester’s thinking in the 1930s that illuminates the strategy he adopted in the 1950s. In the 1936 article, “Religion–Priestly and Prophetic–in the South,” published in the FSC’s journal Radical Religion, Kester laid out a strategic rationale for why the Fellowship should focus at least some of its energies on conservative white congregations.39 Kester started his argument with the simple observation, as religion is such a significant force in the region, that any solution to the South’s problems must take it seriously. Unusually, Kester did not suggest that this work would result in Southern churches joining in on the side of those working to establish the Kingdom of God: “I do not for one moment contend that it is possible to throw the weight of organized Christianity on the side of the class struggle.” Rather, Kester wanted to stop the opposite from happening. He saw the danger being that the churches “can easily completely thwart any attempts to build an equalitarian society in the South” and the “reactionaries . . . will use [organized religion] to crush the very thing true religion seeks to create, namely a human brotherhood.” Kester believed the danger was that conservative reactionaries would co-opt the South’s religious institutions: he hoped the FSC could deny the reactionaries possession of the church. “That it can be prevented to a large measure I have no doubts.”40 By the end of the article, Kester was caught up in his own prose and did not return to his sober and strategic thesis, but he did return to that line of thinking and developed it in the 1950s when the FSC was locked in its losing struggle with the “reactionaries” of Massive Resistance.

During the years of the Depression, the rise of fascism, and the Second World War, the FSC embraced a pacifist and socialist apocalypticism that, in addition to its defiance of the South’s racial conventions of caste and class, helped forge its close bonds of fellowship. “We of this generation are witnessing the inevitable collapse of a world order,” Kester declared in 1939.41 Except, of course, capitalism did not collapse and the G.I.s returned from a world war to a newfound economic prosperity with its “biracial culture” very much intact. In 1944, Kester resigned as the executive secretary of the FSC to become principal of the Penn Normal and Agricultural School on St. Helena island in South Carolina, and so it was up to his successor, Nelle Moreton (1905-1987), to help the FSC adapt to this new world.42

Nelle Moreton came to the FSC in 1945 with over a decade of experience working for the Presbyterian Church in Virginia and New York. Moreton set up the FSC office at First Presbyterian Church in Chapel Hill at the invitation of its minister Charles M. Jones, who was an FSC member and social and theological liberal. Frank Graham, UNC’s college president, was a member of Jones’s congregation and long-time supporter of the FSC. During Moreton’s short tenure as executive secretary—she stepped down due to ill health in 1949—she moved the Fellowship away from Kester’s model of prophetic itinerancy and the support of isolated individual ministers. She developed the FSC’s organization, expanded its operation, and increased its membership. Under Moreton, the Fellowship started professionally printing, rather than mimeographing, its journal Prophetic Religion. It also came to focus its reforming efforts nearly exclusively on the issue of segregation. This was the period when, as historian Moreton Sosna states, segregation “had finally become the race issue in the South.”43 The NAACP, whose membership had expanded dramatically during the war years, launched a concerted legal assault on segregation.44 At the same time, the presidential campaign of 1948 and the emergence of the Dixiecrats signaled the organizing of white reactionaries to preserve white supremacy.

With its center of gravity firmly established in Chapel Hill, in close proximity to the University of North Carolina, the FSC expanded its work with students. The FSC organized a series of interracial summer work camps that ran into considerable local opposition.45 After students experienced threats of mob violence in Tyrrell County, NC, and Big Lick, TN, and arrests in Atlanta, the FSC decided to build its own conference center where students and Fellowship members could meet in safety. In 1948, the FSC purchased 385 acres in Buckeye Cove near Swannanoa in the mountains of North Carolina, seven miles east of Asheville.46 Methodist minister and labor organizer David Burgess helped secure a gift of $8,000 to buy the land and his brother-in-law—a professor of architecture at the University of Florida—drew up ambitious plans for what they all hoped would become a permanent home for the FSC.47

Part of the reason for the demise of the FSC was its constant struggle to raise money. When Nelle Moreton left Chapel Hill and the FSC in the summer of 1949, the FSC owed her $500 in back pay. The organization was in a financial crisis, having started that year with a debt of $2,200—a quarter of the annual budget.48 The FSC was not alone among the liberal and progressive organizations in the South struggling at the dawn of the 1950s. In 1948, the Southern Conference for Human Welfare disbanded.49 The Southern Regional Council started 1950 in debt and saw its numbers continue to decline from 3,400 that year to 1,800 by 1954.50 John Egerton saw common problems plaguing “the organizations that struggled to extend and expand the liberal-progressive initiatives of the thirties into the post-World War II period.” The problems were caused by “a chronic shortage of money and members,” a reliance on money from Northern liberals, and infighting.51

The decline of these liberal organizations came—not coincidentally—at the same time as the ascendancy of the reactionary political opposition to desegregation. In 1950, Frank Graham ran in North Carolina for election to the US Senate, a position to which he had been appointed a year earlier on the death of its incumbent. Graham was a well-known liberal, the former president of UNC, and a member of the FSC. He was defeated in the primary by an opponent who smeared Graham on his weakness on the segregation issue: “If you want your wife and daughter eating at the same table as Negroes, vote for Graham.”52

Crisis in the South (February 1952–May 1954)

By 1952, the committee had restored its finances sufficiently to hire a full time executive secretary to take on the construction of the FSC’s conference center and to help the Fellowship meet the new challenges facing the South. As chance or providence would have it, Howard Kester had just been relieved of his duties after a two-year stint as the director of John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, North Carolina, and was seeking employment.53 The committee invited him to return to the position he had left in 1944 and Kester started work in February. Kester moved the office from Chapel Hill to his own house in Black Mountain, North Carolina. This saved the FSC money and placed the new executive secretary conveniently close to Buckeye Cove, the site of the yet-to-be-built conference center. However, it distanced him from the ready supply of liberal students at Chapel Hill that had proved such a ready resource for Moreton and Jones.54

It was not an easy return for Kester for a number of reasons: the FSC was a different organization than the one he had helped found in the 1930s, and it was a different world. The times had changed in ways that were strikingly apparent to members at the time. Recalling the origins of the FSC during the Depression, David Burgess wrote in 1953, “Today these events seem remote and unreal.”55 The Fellowship’s founding generation, now entering their fifties, missed the close camaraderie of the early years. Scotty Cowan wrote to Kester’s wife Alice, “You put your finger right smack on the trouble with the FSC when you write that it is no longer ‘a Fellowship but an organization.’”56 Don Donahue identifies this rift between the newcomers and the “old timers” as a significant factor in bringing about “the virtual demise of the organization by the late-1950s.”57 The most immediate problem Kester faced, and the one he found most frustrating, was managing the competing demands of building a conference center that required him to spend time at Buckeye Cove and traveling through the region rebuilding the membership. He soon clashed with the new chairman of the FSC, J. Neal Hughley—a professor at the North Carolina College for Negroes—who wanted him to spend the majority of time “in field work devoted to increasing membership support.”58

These internal discussions were taking place in the FSC as racially segregated schooling was heading for a decisive showdown in the courts. In December 1952, Brown vs Board reached the Supreme Court, prompting Herman Talmadge to propose a “private school plan” to the Georgia state legislature the following year designed to thwart a potential Supreme Court decision.59 These were the early days of what historian Jason Morgan Ward calls “a coordinated revolt against the foreseeable.”60 There were also signs that ministers in the FSC who spoke out against segregated schools might face expulsion from their pulpits. In 1951, Charles Jones worked with students supporting the five African Americans integrating the graduate schools of law and medicine at UNC.61 Jones had been an outspoken opponent of segregation since his appointment to the pulpit at First Presbyterian church in 1941, but clearly times were changing and the powers-that-be were now less tolerant of his activism. Jones’s opponents brought heresy charges against the troublesome pastor whose liberal theology did not conform to “the saving tenets and doctrine of the Presbyterian Church.”62 In 1953, the Orange Presbytery, over the protests of the congregation, removed Jones from his charge. Jones’s response was to get ordained in the UCC and become the minister for the nondenominational Community Church of Chapel Hill, a congregation newly formed by exiles from First Presbyterian Church.63

The Fellowship reached its twentieth anniversary in 1954. To mark the occasion, the members held an “Anniversary Kick-off Dinner” on January 20 at Gordon Memorial Methodist Church in Nashville. It was a time of celebration for the “old-timers.” The dinner honored the former Vanderbilt Divinity School professors John L. Kesler and Alva W. Taylor and one of the founders, “Scotty” Cowan, gave the address.64 Even as they looked back over twenty years, it was clear to the FSC that momentous change was coming. Kester speculated “that the forthcoming decision of the Supreme Court may be as far-reaching as the Dred Scott case. In any event, these next few years are surely crucial ones.”65 Eugene Smathers, the FSC’s chairman, wrote to FSC members that same month, “Certain great changes for which the Fellowship has labored, as a small candle in the dark, may come suddenly to brilliant fulfillment—will we and the South be ready?”66 Given the FSC’s resources, it seemed unlikely. Kester, charged with raising money, complained, “Our treasury is almost empty.”67 He also had had to disabuse the executive committee of “the illusion of 700 members.” That spring he reported 417 members on the rolls at the end of 1953, but noted that not all of those were active: only 112 “returned their ballots.”68

The FSC was looking forward to holding three regional conferences in 1954 and attending the World Council of Churches work camp in the summer to continue building cabins at Buckeye Cove, but there was sobering news that spring.69 On March 31, the North Carolina State Baptist Convention fired three FSC members—J.C. Herrin, Jimmy Ray, and Max Wicker—from their jobs for working with students at UNC and Duke.70 The charge, again, was heresy, but all knew it had to do with their progressive views on race. Herrin traced the cause of his dismissal to complaints following his sending a racially integrated group of students to worship at First Baptist Church in Chapel Hill. Herrin recalled, “The chairman of the Deacons met them at the front door and said, ‘What are you bastards doing here?’”71

That same spring, the FSC committee revised the unwieldy and dated Statement of Purpose in preparation for a renewed membership drive. They reduced the old eight-page statement down to two by keeping the principles and removing the subsections that consisted of their programmatic application. The only subsection that remained from the older version—effectively promoting it to a fundamental principle of the organization—was on the freedom of the pulpit. In light of the recent firing of clergy, they revised it to read:

We affirm the freedom of the pulpit as both implicit in our democratic tradition and essential to religious liberty. If this freedom is to remain virile, it must be exercised in the proclamation of a prophetic gospel, in spite of pressures within and without the church exerted by economic interests, hostile social attitudes, and those who would utilize political hysterias to force conformity with their particular ideas. We challenge all who stand in the office of God's spokesmen boldly to exercise this freedom.72

The FSC, comprised of academics and politically engaged clergy and laity, wielded an influence that belied its size. With the Supreme Court’s decision looming, thirty-two of the Fellowship gathered from May 10–12 at Quaker Lake in North Carolina.73 The theme for the conference was blunt: “The Present Crisis in the South.” Attending the conference was the Chairman of the Race Relations Section of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. Kester reported:

[He] presented the statement on interracial policy which was to be presented the following week to the [PCUS] General Assembly at Montreat. The paper was subjected to the most critical analysis and several suggested revisions were incorporated into the final document which was subsequently adopted by the General Assembly . . . in June.74

By then, of course, the Supreme Court had made its decision and the religious and political landscape of the South had become much more dangerous terrain for progressive preachers to traverse.

“A Rare Social Phenomenon” (May 1954 – Spring 1955)

Though long-anticipated by the FSC, the Brown decision on May 17, 1954, precipitated a new sense of responsibility in the organization. The day after the decision, Lewis Everline, the minister at Emanuel Evangelical and Reformed Church, in Lincolnton, North Carolina, wrote to Kester. He wanted to share with Kester what he considered the new task of the FSC: “We will have to be the leaders in this period of adjustment if the transition is to be made in Christian love and patience.”75

It is critical to understand how the Brown decision precipitated a reorientation of the FSC’s mission and theological self-understanding. Before Brown, the members of the FSC understood themselves as engaged in prophetic resistance for the Kingdom; after Brown, they came to understand themselves as about the business of strategic advocacy for the Supreme Court. Kester had spent the preceding thirty years of his life believing not only that the gospel of Jesus Christ required that he fight against racial segregation, but also that only through the actions of true Christians would there be any hope for real social reform. Now change had come, but it had not been brought about by a band of radical Christian prophets, rather it had been through the action of the courts.

Kester spent the summer of 1954 supervising the interracial and international band of students participating in the World Council of Churches’ work camp at Buckeye Cove and so it was not until the fall that he was able to turn his hand and his mind to the intellectual labor that the hour demanded. In the FSC’s October newsletter, Kester processed this new post-Brown reality. “It is, I believe a rare social phenomenon that an organization whose basic concepts were a mere two decades ago regarded as radical, if not revolutionary, sees them established in the fundamental law of the land.” He encouraged FSC members to “rejoice” at this victory of a “good, sound and wholesome democratic and Christian doctrine.” But as the reform had come from outside the church, it functioned for Kester simultaneously as a judgment on, and a prophetic challenge to, churches in the South. Since the Court had “set aside fiction and established the fact of every man’s right to freedom, equality and justice squarely in the basic law of the land,” it called “the church of the living God, to give heed to its long-neglected ideals of righteousness, mercy and love.” Here was the FSC’s new task: to help white churches in the South “give heed” to the prophetic call of God issued by the Supreme Court of the United States of America. “If we of the churches fail now to move our congregations to a full and unequivocal acceptance of what, since Christ, has been the law of love and now becomes the fundamental law of the land, we will signally fail our day, our nation and our God.”76

Despite the fact that the Supreme Court had mandated the end of separate and unequal education, the justices had issued neither a timeline nor guidelines for how this should happen.77 This ambiguity seemed to Kester to suggest a vital role for the FSC. He believed that the end of legal segregation in the South was “inevitable,” but correctly sounded a note of caution. “We understand that we are but on the edge of the achievement of this ancient dream. We cannot now drag our feet on the assumption that our ideas have carried the day.” He spun out an extended metaphor to make his point: “We must not believe for a moment that the great road to national brotherhood has been thrown open to all travelers. Only the main highway sign is up indicating the direction, but also saying ‘Road under repair, travel at your own risk, detours and barricades ahead.’” At this point, a note of Niebuhrian realism and tragedy crept into Kester’s argument. He warned that the churches as institutions could actually be the enemy of progress. “The great road of human brotherhood will not be finished soon nor well, or perhaps at all, if we who have so long labored to walk in freedom upon it fail now to vigorously help remove the roadblocks, the barricades and keep our churches from becoming a deadening detour.”78

Kester’s strategy for preventing white churches from becoming a “deadening detour” had changed little since his first efforts as the FSC’s secretary in the 1930s. It involved the publication and distribution of literature, the organization of local state and regional conferences with churches and students, and “circuit riding” to the “hot spots.”79 One new proposal was to hold small workshops across the South to help ease the transition of desegregation. A week after the news of the Supreme Court’s decision, Kester wrote to foundations seeking grant funding for this enterprise. He explained that, “While segregation has been outlawed by the Supreme Court, its achievement will be realized as we build solid community support for it and help those unaccustomed to interracial work to make the first and all-important steps.”80 The FSC planned to do this by holding “small area conferences–for one to two days.”81 This would help local communities “make the necessary adjustments toward an integrated and non-segregated school system and similar public agencies and institutions, and to help church-related colleges and secondary schools—of which there are a vast number in the South—open their doors to Negroes.”82 Kester also hoped to “organize several teams of university and seminary professors and students for inter-seminary and church-related college visitations.”83

While Kester’s analysis of the dangers facing desegregation was prescient, his plan to run a series of workshops across the region was naïve given the resources of the FSC. In December, a somewhat chastened Kester notified the members that in the new year he would be “holding as many one and two-day conferences across the South as time, money and energy permit, and to visit, develop, and organize as many new groups as possible.”84

In an unholy and unbalanced symmetry, at the same time as Kester and the FSC were planning how to foster local white support for desegregation, the reactionary forces bent on preserving segregation and white supremacy also decided to hold local meetings to build community support for their cause. In June 1954, Senator James O. Eastland of Mississippi started promoting a grassroots resistance movement he hoped would develop in the South:

It will be a people’s organization, an organization not controlled by fawning politicians who cater to organized racial pressure groups. A people’s organization to fight the Court, to fight the CIO, to fight the NAACP and to fight all the conscienceless pressure groups who are attempting our destruction.85

The movement Eastland longed for found its most successful expression in the Citizens’ Councils. Starting with a small meeting of businessmen on July 11 just a few miles from Eastland’s plantation in the Mississippi Delta, Citizens’ Councils reported 60,000 members in Mississippi alone by August 1955.86 Just like the FSC, the reactionaries had connections with supportive ministers and seminary professors. On December 14, 1954, 275 Methodist ministers and laymen gathered from across the South at Highlands Methodist Church, in Birmingham where they established the Association of Methodist Ministers and Laymen to counter the official integrationist stance of their national denomination.87

The Citizens’ Councils and organizations such as the Patriots of North Carolina, and Virginia’s Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties all printed newsletters and pamphlets making their case.88 Much of the literature, such as retired seminary professor Rev G.T. Gillespie’s popular tract, A Christian View on Segregation, included “biblical” arguments for segregation.89 Among the most widely circulated pieces of literature was Judge Tom Brady of Mississippi’s 90-page pamphlet, Black Monday, published in June 1954.90 Historian Neil R. McMillen described it as a “hastily written, unabashedly racist manifesto.”91 Brady, it should be noted, was a deacon and a Sunday school teacher at the First Baptist Church in Brookhaven, Mississippi.92

The same month as the first Citizens’ Council meeting, the FSC started work on its own manifesto. Scotty Cowan wrote the first draft and then Kester and the other members of the committee worked over successive drafts. It was finally printed a year later in July 1955 as a “special edition” of Prophetic Religion and then reprinted as a pamphlet.93 Cowan and Kester gave their manifesto the grand title, “A Letter to the Christian Churches in the South”—it called for nothing less than a “new reformation” of the Church.94 They hoped it would be “widely used in our church schools, high schools, seminaries and colleges.”95 With its two columns of small print spread over twenty-three pages, the letter was too long for anyone but the most committed reader. Written by a committee, the authors’ collective experience over twenty years left them with too much to say and too many competing interests. There was also a new tone of hesitancy in this epistle; even after a year in the writing, the preface included the statement “It is our hope that the reactions which we receive may eventually be combined into a more adequate statement.”96

While it did not become the widely circulated and influential document its authors hoped, “A Letter to the Christian Churches in the South” is significant in at least four ways.97 First, the labored process required in writing the document demonstrates the difficulty some members of the FSC had shifting gears from prophetic resistance to strategic advocacy. One appreciative member commented upon reading the finished product, “The tone is still the fervent Scotty [Cowan] tone . . . It sounded the old tones of ferver [sic] familiar and important to many of us who are older members of the Fellowship.”98 Cowan’s prophetic and martial voice is indeed evident throughout the document, asking the reader, “Are our churches advanced fighting posts for the Kingdom of God or mere clubs in which men gather for communal comfort?”99 However, the same reader appreciated the strategic additions and edits the committee had made as now, “the ideas are not (as with the original draft) those that would alienate the very people you wanted to reach.”100

Second, "A Letter to the Christian Churches in the South" unambiguously shows that the FSC did not consider racial segregation in any form a theologically acceptable position for churches.

Some churches in the South are set for segregation and are carrying out this practice in the name of Christ, thereby crucifying Him afresh and putting Him to open shame. A church existing in a pattern of segregation imposed by society is a living lie, a Judas in its betrayal of Christ.101

To be for segregation meant you were not a Christian church and, looking around, there did not seem to the authors to be too many of those: “On the basis of desegregation there are few Christian churches in the South.”102

Third, in its extended and powerful jeremiads against white southern churches, the letter reveals the strength and insight of the FSC’s distinctively southern brand of neo-orthodoxy.103 Here, the FSC was comfortably on its home ground with the “old tones” of prophetic resistance. The authors bemoaned the fact that churches lagged so far behind secular institutions. “Churches who proclaim the universal love of God and deny it in practice,” they pointed out, “should bow in shame before colleges and universities, labor unions and medical societies, political and athletic groups, which have risen above racial prejudice.”104 They decried the failure of churches to engage politically: “Groups fighting for social justice and looking to the churches for help have all too often looked in vain. In a day when freedom is at stake, when its foundations in America are being whittled away by those lusting for ‘pelf, privilege and power,’ the churches at the local level are strangely silent.”105

Finally, the letter shows that by 1955 the FSC understood itself as facing a numerically superior and newly constituted force of false prophets. This, at least, was familiar prophetic territory for the FSC and clearly Cowan and Kester felt at home in their response: “When a considerable number of our brothers organize under the banner of the Christian church to annul both the law of the land and the law of God and Christ, the time for a Reformation is here.”106 The letter ended with a flourish of prose so lofty that the readers surely felt that the God of the King James Bible must have been on the side of its authors: “Cry aloud for righteousness the Church must or lose its own soul. Repent and believe the Gospel, and bring forth fruit meet for repentance or we perish. That the Church fail not in her divine task is our hope and our prayer. Amen.”107

“A Letter to the Christian Churches in the South” was one of two pamphlets distributed by the FSC to try to persuade white southern churches to support the Supreme Court’s decision. The second was a reprint of Frank Graham’s article, “The Need for Wisdom: Two Suggestions for Procedures in Carrying Out the Supreme Court’s Decision Against Segregation,” originally published in the Spring 1955 edition of the Virginia Quarterly Review. The liberal Graham, a long-time supporter of the FSC, had what historian Morton Sosna described as, “an innate ability to justify his actions in terms white Southerners could understand.”108 In September 1955, the FSC started distributing 40,000 copies of Graham’s article.109 “The Need for Wisdom” was very different in tone and content from “A Letter to the Christian Churches in the South.” Graham eschewed confrontational prophetic pronouncements; instead, he appealed to the region’s liberals to advocate for peaceful change in their “churches and local communities.” He hoped that the acceptance of court decisions would come through “changing the historic customs of the people in one third of the states of the Union through the . . . influences of religion and education in the minds and hearts of the people” rather than through “Congressional action.”110 Despite his clear opposition to segregation, Graham sounded the gradualist notes that many white Southerners, including those opposed to ever implementing the Court’s decision, wanted to hear: the Federal Government would do well to leave southern whites to sort out the issue of segregation themselves, in their own way, and in their own time.

“The Presence of Terror” (Summer 1955–March 1956)

Howard Kester and his wife Alice spent the summer of 1955 working with students at Buckeye Cove and sorting out the details for printing both the FSC’s Letter to the Christian Churches in the South and Graham’s article. At the same time, news reached them in the mountains of North Carolina of the growing force of the resistance to desegregation. On May 31, the Supreme Court finally issued a ruling on the timeframe for the implementation of the desegregation of schools: it should proceed at “all deliberate speed.”111 Brown II encouraged and emboldened segregationists who read “all deliberate speed” to mean sometime-never. On June 22, 1955, five thousand people attended a Citizens’ Council rally in Selma, Alabama; twelve state senators sat on the platform. The speakers included Herman Talmadge of Georgia, and Robert Patterson and Judge Brady of Mississippi.112 In Mississippi, the birthplace of the Citizens’ Councils, there had already been two civil rights related murders that summer of men working to register voters; then on August 28, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam lynched Emmett Till outside Money, Mississippi.113

In September, as the farcical Till trial held the attention of the news media, Kester was planning a tour through the “Lower South” to visit FSC members in Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Alabama, and Georgia.114 Before setting off with Alice, Kester wrote to his friend David Burgess explaining their plans to conduct “workshops on integration.”115 Primarily though, Kester understood the task of his trip was “to bolster up some of the boys and girls who are taking a licking in some of our churches for their faithful stand on the side of the blessed Lord.”116 Bad news continued to come in. On September 30, Kester wrote to a couple of the attendees from the WCC summer work camp:

The situation down here is getting tighter and rougher with each passing day. Crosses burnt in Columbia S.C. Thursday night and two of our best friends-long-time-members of the FSC-Gene Cox and Doctor Dave Minter together with their families petitioned to leave Mississippi after four large [Citizens’ Council] mass meetings.117

Cox and Minter were at Providence Farm near Cruger in Holmes County, Mississippi (just 25 miles South of Money), an interracial cooperative farm and health clinic started in 1939.118

Kester spent two weeks of October in Jackson, Oxford, and Starkville, Mississippi meeting with ministers and laypeople.119 These included the noted liberal newspaperman Hodding Carter and the maverick YMCA chaplain at the University of Mississippi, Will Campbell.120 This was the first time Campbell and Kester met, though they had corresponded over the situation at Providence Farm. Campbell had first encountered the FSC as a student when he heard Clarence Jordan of Koinonia Farm speak at Wake Forest.121 Now, as he tried to help Cox and Minter at Providence Farm, he found himself under increasing pressure. Kester, after visiting with Campbell at his home in Oxford on October 9–10, summarized the situation: “Will is now in the hot seat at Ole Miss.”122

Kester witnessed firsthand the growing power of the Citizens’ Councils in Mississippi. Just a couple of days after his meeting with Campbell, councils from twenty counties in the state formed the Association of Citizens’ Councils of Mississippi and that same month, published the first edition of their monthly newspaper The Citizens’ Council.123 When Kester reached Providence Farm, he found the small community under extraordinary pressure to leave the state. “The Cruger situation is well nigh unbelievably bad,” Kester wrote immediately after his visit, “worse in some ways than the ones I faced there twenty years ago.”124 It is evident from his correspondence that Kester found the situation both familiar and exhilarating. He was meeting with brave and outspoken ministers and was back in the part of the world where, in the 1930s and 40s, he had done some of his most significant and dangerous work organizing the interracial Southern Tenant Farmers Union and investigating peonage and lynching. “At times I felt the presence of terror as I had not felt it since the days in Arkansas,” he explained to David Burgess, “and that is saying a good bit.”125 This work felt far more significant than struggling to build a conference center in North Carolina—encouraging the prophets to stand up and proclaim the good news of a gospel for which violence and racial hatred were anathema was the work he not only knew but that he was also good at. Others thought so too. One African American minister from Mississippi explained the importance of a visit from Kester: “Buck Kester [had] a way of making a man feel he is courageous when he ain’t.”126

From Mississippi, Alice and Howard Kester drove to Louisiana and then to Texas. On November 9, they reached Austin where they received a warm welcome from Blake Smith the pastor at the University Church, a congregation that the Austin Baptist Association had expelled in the late 1940s for welcoming African Americans as members.127 By the time they made it back to their home on Black Mountain, the Kesters had driven over 3,500 miles. Though physically exhausted, Kester was excited about the prospects for the FSC. “The trip through the Southwest was the most heartening experience I have had in years,” he told David Burgess. “Everywhere I found an almost unbelievable interest and concern in the FSC, especially in Texas. In Miss. we were far better known than I thought possible.”128 He also believed he had a plan to counter the rising power of the Citizens’ Councils.

Fresh from meeting with the brave but isolated souls in Mississippi, Kester hoped to bring the right-thinking yet silent moderates into the fray. “I do believe I know the means by which we can bring the liberals and moderates together into a strong movement to combat the Citizens Council,” he wrote to Burgess.129 By enlisting the timid moderates, Kester envisaged building, “a solid phalanx of Christian men and women” to counter the Citizens’ Councils hold over white churches.130 He clearly saw the FSC in a battle with the Citizens’ Councils for influence, “If we can ever get the Council on the run—and they have the bit in their teeth now—we can move on to the next step.”131

Kester thought the FSC was in a much better position to offer serious opposition to the growing forces of massive resistance than either the Southern Regional Council favored by white liberals or the NAACP favored by activists. His dismissal of the SRC was probably fair: “The Southern Regional Council is pretty much a washout: certainly in those states in the Deep South from which the impetus for the whole struggle is coming it is virtually non-existent, an abundance of dollars but no sense, a paper organization with little leadership and less following.” Kester’s problem with the NAACP is a little harder to understand. He had worked closely with the NAACP in the 1930s. Now, however, he considered the organization “so far ahead of the crowd that it has lost sight of the basic struggle.” With the Citizens’ Councils’ censure, intimidation, and boycott of Providence Farm foremost in his mind, Kester thought that the enforced desegregation of schools precipitated by the NAACP’s focus on challenging segregation through the courts was premature. Kester believed there were “prior concerns” of “civil democratic and Christian rights and privileges.” These had to be addressed before anyone could tackle the integration of schools. “Before we can talk about integration in some of these places we first have got to get the right just to talk.”132

It is quite possible that Kester’s desire to be released by the FSC committee to engage in meaningful work caused him to exaggerate both the shortcomings of other organizations working for civil rights in the South and the possibilities for the FSC to have a significant influence in the region. Since returning to the FSC in 1952, he had become increasingly frustrated with the tasks of fundraising for a conference center that no one seemed to want to support and trying to develop the property with limited resources. Now a great religious drama was unfolding and, after his road trip that fall of 1955, he believed he knew what God wanted him to do. “Of course I would like to do this job as difficult as I know it will be,” he confessed to Burgess. “I know how to do it and it would be the grandest day of my Christian ministry to tie together these really brave Christians who are now so alone and so lonely.”133

Rightly convinced of the urgency of the hour, Kester wasted no time in putting his plan before the FSC leadership. On the November 29, he met with Tartt Bell (Director of the American Friends Service Committee’s Southeastern Regional Office) and Charles Jones in Greensboro.134 Together they came up with the idea of having a small meeting of the region’s liberal Protestant leaders. The FSC set the meeting for January 10–11, 1956, to be held without fanfare outside Nashville at Camp Dogwood. The Field Foundation agreed to support the meeting with a grant of $1,500, to which they added an additional $500 to “clear all expenses.”135 With a target guest list of only thirty-five, Kester was determined not to invite the usual suspects: apparently, he did not extend the invitation to all the members of FSC executive committee. Instead, the organizers were “committed to range beyond our membership and bring in people who occupied strategic professional responsibilities in the various denominations”136

The invitation Kester sent out explained, “The objective of this informal assembly is to find ways to strengthen at once the Christian witness being made by the Churches in the face of tensions rising so rapidly across the south.”137 The invitation demonstrates the pressure liberal white clergy felt to conform to the rapidly solidifying consensus in white institutions, including their own denominations, against integration. Kester reassured the invitees, “You are invited to attend as a concerned individual, representing officially no local, denominational or other church related group . . . Your attendance will in no way commit you to any suggestions for action which may be made. There is to be no publicity.”138 However, Kester hoped, among other things, that the meeting at Camp Dogwood would work “in some way to build some spine into denominational leaders, administrative personnel, social action secretaries, presiding elders or as they are now called district superintendents, bishops, etc. etc.”139

Some significant denominational leaders attended the meeting—Malcolm Calhoun, Division of Christian Relations of the Presbyterian Church US, and A.C. Miller, Secretary of the Christian Life Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention—though fewer than Kester had hoped. Also present were officers of the National Council of Churches, a collection of seminary professors, Frank Graham, and Will Campbell drove in with a carload from Mississippi.140 At the meeting, Kester first proposed his idea “to call a regional-wide meeting of Southern Churchmen,” a proposal which the group received with interest.

A second proposal to come from the meeting was for the FSC to produce a response to all the literature flooding the South which argued that segregation was biblical.141 As Kester explained to the FSC membership in April:

Few things are more scandalous and dismaying than the way in which the Bible is being used by segregationists to uphold their point of view . . . very little has been done to offset this barrage of infidelity and ignorance by providing material which sets the Christian view in its proper perspective.142

The task of writing a 100-page book fell to Everett Tilson of Vanderbilt Divinity School. Kester asked members to send examples of segregationist literature to Tilson.143 His book, Segregation and the Bible, was not published until 1958 after Kester had left the FSC and the organization had ceased having any active role in the movement.

There is a broad consensus among historians that those arguing for integration and civil rights had a much easier task mustering coherent theological arguments to inspire their cause than did their opponents.144 David Chappell goes further to argue that this prophetic advantage helps explain the victory of the civil rights movement over the religiously less-coherent reactionary forces of die-hard segregationists.145 While the “civil rights . . . believers’ inspiration to sacrifice and solidarity” clearly contributed to their political victory in the battle for civil rights, it is worth noting that theological coherence did not seem to give any such decisive advantage to the FSC in its battle for the soul of the white Protestant churches in the South.146

The anti-integrationist arguments for segregation were, as the FSC characterized them, a “barrage of infidelity and ignorance;” however, it would be a mistake to think, as Chappell argues, that their proponents were aware of the weakness of their own “biblical” arguments.147 The seriousness with which Kester and the FSC took the power and pervasiveness of this “segregationist folk theology,” confirms historian Jane Dailey’s assertion that this was “a yet undecided struggle for the crown of orthodoxy.”148

It was not a lack of prophetic zeal or weakness of argument that led to the failure of Kester and the FSC in their self-appointed task of halting the reactionaries from using, “the House of the Lord . . . [as] an instrument—a whipping rod—in the hands of the Citizens’ Council.”149 At least some of the blame lies with the infighting among the liberals, as an incident that occurred at Camp Dogwood that January in 1956 reveals. Excited by his own vision for the way the FSC should proceed, Kester did not respond well to the “Chapel Hill-Raleigh group” questioning his performance as the Fellowship’s secretary.150 They seem to have queried both the time and effort Kester had expended trying to build the conference center and his new plan to drop everything and “go about the region—especially the lower South . . . contacting liberals and putting them in touch with neighbors, friends in their immediate or nearby community.”151 This seemed to them to be taking the FSC backwards. Chief among Kester’s detractors—as he understood them—was J. C. Herrin. Kester wrote to Eugene Smathers, the chairman of the FSC, “I regret a thousand times that I lost my temper with Herrin at Camp Dogwood.” Kester tried to appeal to the old timers for support. “It is true that the few people who gathered themselves around Nelle [Moreton] at Chapel Hill have sought to make the FSC something it never quite was intended to be, and couldn’t possibly be now without scads of money and personnel.”152 Kester demanded a “full meeting of the Executive Committee to the end that the air may be cleared and I, for one, can find out where I stand and what the Fellowship really is and what it is that we want to do.”153 Eugene Smathers, the chair of FSC, urged him to be “cleansed of bitterness.”154

Kester’s daughter described her father as a man who was not “particularly psychologically attuned. There were things he didn’t understand about why people reacted as they did, and he could be hurt rather easily . . . when he was hurt by some kind of rejection . . . his struggles were really very intense . . . He had a tough temper.”155 All of these character traits displayed themselves in his reaction to the criticism at Camp Dogwood. Kester, who experienced bouts of depression, intimated that he could not continue in his work, “I fear that concern is slowly ebbing away, or perhaps it has ebbed and now I look toward other things and other fields. The carping criticism, especially by those who hardly lift a hand to help, is too much, very much too much.”156 At the end of February, after weeks of brooding, Kester sent the committee a letter of resignation. It included the petulant and despairing aside that for the next meeting of the executive committee in April, “the knowledge that my own shortcomings need not further handicap the Fellowship might be a boon.”157 David Burgess told Dallas Blanchard that he “went to the South with three heroes in mind. One was Buck Kester . . . I discovered in the fullness of time that everyone has feet of clay.”158

Oddly, Kester did not offer a date for his resignation. “I would assume that you would want me to carry on through the summer conference,” he suggested. He promised to continue with the FSCs fundraising and the fieldwork but by the end of his letter of resignation, he felt he needed to remind the readers (or maybe himself), “Obviously I will soon have to begin to look for another job.”159

Even as Kester stewed over the FSC’s lack of appreciation for his work, he was paying close attention to the rising power and boldness of his real enemy. On February 6, there were riots in Tuscaloosa surrounding the integration of the University of Alabama by Autherine Lucy. The school responded by suspending its first African American student.160 Kester, ever the prophet, saw these events in Manichean terms. “The effort was defeated by and large by the Citizens’ Councils of more than one state. They succeeded in their efforts partly for the reason that the children of light did not apprehend the lengths to which the children of darkness would go to destroy this tiny effort toward good faith in fulfillment of the law of man and God.”161

Kester’s response was to continue to flesh-out his plan for stopping the Citizens’ Councils. On February 22, he sent Gene Smathers a three-page manifesto with the title “A step toward building a democratic-Christian front in the Deep South.” It is a surprising response from a man who naturally saw the world as a battle between “the children of light” and “the children of darkness.” After the riots at Tuscaloosa Kester believed there was a very real possibility that the region, torn between two polarizing forces, would descend into “violence and hysteria.” What was needed, in Kester’s opinion, was “a middle way.” If one could not be found then “the present situation will undoubtedly worsen and as it worsens decades may be required to heal the wounds of children yet unborn.”162 In this document, Kester clearly articulates the idea that finding this middle way would involve compromising over the issue of segregation. To “build a native opposition to the Citizens Council . . . an opposition . . . which is already in evidence, but which lacks support and backing” would require welcoming in white liberals who hold that integration needed to come more slowly to the South. Kester argued:

[White liberals] find themselves in the crossfire between those determined on the one hand that desegregation and integration must be achieved immediately and forthwith and irrespective of the price that may be paid . . . and those who are equally determined that segregation shall continue so long as there are men and guns to maintain it. These are the “gradualists” or “moderates” who reckon with deep seated prejudices, old patterns of behavior and believe a bit of patience, faith and common sense can work a miracle of human integration, respect and goodwill where neither edict nor bayonet can move men against their will.163

It is difficult, reading this document, not to conclude that Kester now shared at least some of the concerns he attributed to the gradualists and moderates:

These men and women can find little wisdom or comfort in aligning themselves with organizations and agencies such as the NAACP. Their cause can best be served by adherence to the cause of democracy and the Christian faith, and by building a movement which rests primarily on these foundations.164

Kester indicated the degree to which he was prepared to compromise his prophetic religion to build his coalition for this middle way. In the Fellowship’s newsletter in April he described the influential whites of his acquaintance in the Deep South who were, like himself, “university trained and stamped by an association with the YMCA or other campus religious organization.” Some of them, motivated by both a paternalistic desire to maintain the status quo and eventually to comply with the Supreme Court’s decision, were organizing meetings with members of local black communities, “both to retain such semblance of good will as had been built up over the decades and to keep the hounds of Senator Eastland and Judge Brady from running riot.”

These were the Atticus Finches immortalized in To Kill a Mockingbird that Kester had come to know in the 1920s and 30s, the kind of men and women who had been sympathetic to the CICs efforts to end lynching. Now in the 1950s, just as Harper Lee described Atticus in Go Set a Watchman, Kester found, “These men are members of the church and sometimes, for their own good reasons, members of the Citizens’ Councils.” But unlike Scout’s repudiation of her father for joining the Citizens’ Council in Lee’s novel, Kester believed these men had “courage of a rare nature” and should be recognized by the FSC as allies against the reactionaries.165

Benjamin Mays, in an interview shortly before his death, expressed his disappointment that Kester, by his assessment, had changed from the “pretty radical fellow” he had first met in the 1930s who had impressed him with his “vigor and courage.” Mays contended that “a lot of people don’t realize that Kester did change and he was out of tune with the radicals.” Mays was certainly correct in his assessment that, by the 1950s, Kester “was out of tune with the NAACP.”166 While he may not have been the radical he once was, Kester was still attracted to the emerging generation of southern civil rights activists. In March 1956, having submitted his letter of intent to resign at some future date, Kester went on a three-week road trip through Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama.167 He visited FSC members in Berea, Lexington, Nashville, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa (the scene of the recent riots). Finally, he visited Montgomery where the bus boycott was now in its third month. “The singularly wise leadership being provided by both white and Negro ministers,” particularly impressed him. Witnessing the boycott confirmed to Kester the possibility of finding a way that avoided violent confrontation. He also found the experience confirmed his long-held conviction that the church could be a key contributor to the transformation of the South. As Kester explained to the FSC members in his report on the trip, “Those who have consistently discounted Southern parsons would do well to take a first hand look-see for themselves and in doing so take a fresh grip on their hearts for surely they are in for the kind of shock for which we can humbly thank God.”168

It is not clear whether Martin Luther King Jr. was among the ministers with whom Kester met when he was in Montgomery, he does not mention him by name in his report. However, Kester was surely talking about King when he wrote, “I was never more conscious than now of the vast influence of one man who is the faithful servant of Christian idealism may have on the ebb and flow of history.” For Kester, King epitomized the spirit and the potential of the lone prophet/preacher that the FSC had championed in the 1930s. “One man I know—lonely and unafraid—in a little church in a little town in Alabama, has by his steady courage and faith set many other lonely men fearlessly to embrace the life-giving articles of his democratic and Christian faith.”169

At the same time that Kester was encouraged by what he witnessed in Montgomery—the proponents of Massive Resistance gained a significant victory. That March, 19 U.S. Senators and 81 members of the House of Representatives signed the Southern Manifesto declaring, “We commend the motives of those States which have declared the intention to resist forced integration by any lawful means.”170 “The situation generally could hardly be more discouraging,” Kester wrote. “Perhaps it is the inevitable darkness before the dawn. I hope so.”171 Kester’s hope seemed foolish. The Southern Manifesto appeared, at the time, to herald the inexorable ascendancy of Massive Resistance. In April, 65 leaders from Citizens’ Councils across the southern states met in New Orleans and founded the Citizens’ Councils of America “for the preservation of the reserved natural rights of the people of the States, including primarily, the separation of the races in our schools and all institutions involving personal and social relations.”172 The Citizens’ Council movement reached its peak in that year with an estimated membership of around 250,000, many of them churchgoers.173 As historian Neil McMillen points out, “a sizeable portion of the movement’s leadership came from the Protestant clergy.”174 Despite this clerical support, the Citizens’ Councils continually issued warnings to white southerners to view their pastors trained at liberal seminaries with suspicion. An alliterative editorial in the Jackson Daily News declared, “Puny parsons who prattle imbecilic propaganda in pulpits about obedience to the Supreme Court desegregation decision being a ‘manifestation of the Christian spirit’ ought to have their pulpits kicked from under them and their tongues silenced.”175

“A Great Christian Rally” (April 1956 – April 1957)

The FSC’s executive committee met on April 3–4, 1956. Kester’s oldest friends and strongest advocates, Eugene Smathers and Scotty Cowan, were unable to attend. Even without his allies present, the committee accepted both Kester’s decision to quit his job and his offer to keep working through the summer to get Buckeye Cove ready for the FSC’s annual conference. They agreed to Kester’s plan to hold a “Southwide Conference on Integration” and resolved that the Spring issue of Prophetic Religion should give “an answer to the ‘Manifesto’ of southern legislators.”176 The FSC lacked the funds to print the journal but Kester did draft “A Southern Reply to the ‘Manifesto’ Issued by 99 Senators and Congressmen.” In it, Kester wrote, “[The Manifesto] appears to commit Southern life to an intellectual and spiritual straitjacket from which there can be no escape short of violence and bloodshed.” He did not equivocate in declaring that “the ruling of the Supreme Court was timely and right.” Sitting uncomfortably alongside this position was Kester’s developing gradualism. “If the ‘Manifesto’ had upheld the Court’s decision by asking for sufficient time to make the essential adjustments,” then Kester believed, “an overwhelming majority of Southerners would have thanked God that at long last the nightmare of inhuman, undemocratic and un-Christian practice was drawing to an end.” He ended the reply with a clarion call, “The time has come when we men and women of the Protestant churches of the South must come together in a great Christian Rally; come together to give our unequivocal and utter support to the decision of the Supreme Court; to our nation and, above all, our Lord.”177

Kester immediately set about trying to secure speakers and funding for the rally. In a letter to the president of the Robert Treat Paine Foundation in Boston, Kester explained that he hoped the rally could happen “some time between Thanksgiving and Christmas [1956] as the need is urgent.”178 Kester stated he had already invited 80 dignitaries to the conference, which was intended “to rally the support of Protestants to the support of the decision of the Supreme Court on desegregation and Integration . . . to give witness and to take counsel of one another regarding what the churches must do in this time of trouble and heightened tension.”179 This, like many other appeals Kester wrote to foundations, was politely declined.180

With the FSC’s coffers almost empty, Kester experienced another demoralizing setback. The Fellowship had anticipated holding its annual conference in August for the first time at Buckeye Cove, the place that so many of them had contributed to and worked on building the cabins, kitchen, and meeting hall. Kester had been the project manager since his return to the FSC in 1952 and had managed to struggle forward with the project using ingenuity, local materials, and volunteer labor. In July, the Buncombe County Department of Health and Sanitation, after inspecting the facilities on the property, forbade the FSC to use the camp for the summer conference.181 Despite the executive committee’s dutiful claims to the contrary, without adequate funding to install all the plumbing and sewage the county required, this effectively marked the end of the FSC’s dreams of having its own conference center.182 Kester experienced this as an embarrassing personal failure while, at the same time, harboring anger and resentment that without the necessary financial support for the project from charitable foundations or FSC members, the committee had set him an impossible task. Calling it “this summer of crisis,” Kester wrote to the members of the FSC in September. “The efforts of the summer have been anything but encouraging,” he stated. “The fact is I can’t remember a more discouraging one but underneath our sorrow and trouble lies the dawning of a new day. I am certain that I must leave the work of the Fellowship just as soon as possible.”183

There were other reasons for Kester to label the summer of 1956 the “summer of crisis.” Two projects closely associated with the FSC and its affiliated organization Friends of the Soil came under attack. In Georgia, unknown assailants tossed fifteen sticks of dynamite at Koinonia Farm’s store.184 In Mississippi, Gene Cox and David Minter finally had to bow to the pressure from the Citizens’ Councils.185 “I saw Gene a few days before he left Providence,” Will Campbell wrote in a letter to Kester on September 7. “It was a sad occasion to see them all pulling out of that valley.”186 Campbell himself had lost his job at the University of Mississippi because of his stance on integration and was moving to Nashville to set up the Southern Office of the Department of Racial and Cultural Relations for the National Council of Churches.187

With the work at Buckeye Cove at an impasse, the executive committee made the rally the FSC’s “major emphasis.”188 The committee wrote to the Fellowship drumming up support for the plan. “To have the kind of vital meeting so urgently needed, we must have the active support of the whole Fellowship. This is an all-out effort to rally the liberal Christian forces of the South—Virginia to Texas.”189 Over the summer, Kester had talked with church leaders in Nashville and decided that that would be the best place to hold the event. Will Campbell agreed to help with the planning and invited Howard and Alice Kester to work out of his office.190 At the Executive Committee’s meeting in October, Kester “reaffirmed his intention to resign,” but offered to “stay on in order to round out two or three projects—especially the Southwide Rally on Integration.”191 The committee felt that after Kester’s years of service, they could accommodate his ambivalent retreat from the job, but they also lacked the funding to promise that the salary could continue. That fall, the FSC learned that the Doris Duke Foundation and the Field Foundation—the FSC’s only major donors—would not be continuing their support.192