“A Doorkeeper in the House of My God”: Female Stewardship of Protestant Sacred Spaces in the Gulf South, 1830-1861

Emily Wright

Emily Wright is a Ph.D. Candidate in History Department at Tulane University.

Cite this Article

Emily Wright, "'A Doorkeeper in the House of My God': Female Stewardship of Protestant Sacred Spaces in the Gulf South, 1830-1861," Journal of Southern Religion (21) (2019): jsreligion.org/vol21/wright.

Open-access license

This work is licensed CC-BY. You are encouraged to make free use of this publication.

Click here to access MAVCOR Journal site for the special issue.

“I had rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God, than to dwell in the tents of wickedness.” - Psalm 84:10 (King James Version)

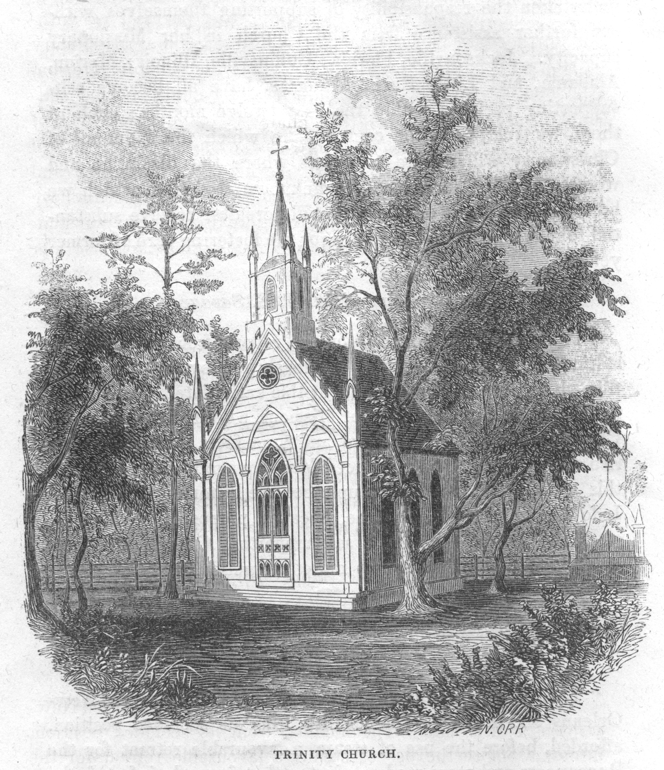

In 1854 Thomas Savage, rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in the Gulf Coast town of Pass Christian, Mississippi, submitted two items to the Episcopal Board of Missions: a sketch of their new Gothic Revival church drawn by his wife Elizabeth (Figure 1).[1] Over the next few years, while the male members of the congregation elected a vestry and collected a meager sum of subscriptions, the female members formed themselves into a church aid sewing society, which raised over $2,000 for church construction—almost the entire cost of the building—as well as $580 for a new organ, all by selling their sewing projects and collecting donations. As Savage explained it, “To woman, first and foremost in every good work, we are indebted under God, for the origin, progress, and completion of this enterprise,” which he argued was “one of the finest structures of its size and style in the Southern country.”[2] These women prompted the initial discussion about constructing a new church building, organized their own church aid society, fundraised, and made furnishing decisions and purchases, thus endowing the structure with the material trappings of a respectable Protestant church.

This picture of late antebellum public female stewardship—of women using their time, talent, and treasure to build and furnish church structures—challenges the prevailing historical narrative of southern Protestant development. According to this narrative, first made popular by Donald Mathews, in the early years of the Second Great Awakening, southern Protestant women held religious power in the public sphere by hosting worship services in their homes, advising and supporting itinerant preachers, and evangelizing to members of their community. By 1830, however, as male preachers settled down and built churches, they no longer needed women to host and advise them and congregations adopted mainstream and patriarchal church structures. While women remained a passive majority in the pews on Sundays, their spiritual power was “domesticated,” moved into the private sphere to concentrate on converting their children and being modest, self-sacrificing examples for their husbands.[3] While northern antebellum churches after 1830 offered women the space to work publicly and to create female religious associations, this was not the case in the South until after the Civil War. This was due to southern women’s rural isolation and the need to keep white male authority in a slave society unquestioned.[4] Scholarship on female stewardship in the late antebellum (i.e. post-1830) South focuses only on the urban South or the private donations of wealthy widows.[5]

Moving beyond the East Coast, however, it is clear that public female activism was widespread and essential to creating a built Protestantlandscape in the more recently settled Gulf South of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—well beyond 1830. Unlike on the East Coast, the Episcopal Church was not an established church in the Gulf South; its antebellum story here closely follows that of mainstream evangelical Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian denominations, as all tried to establish themselves at the same time and all relied on women’s public activism to succeed.[6] Nor did it take a war effort for southern women to start organizing collective female associations like sewing societies to fund community projects.[7] The movement to build and furnish new churches in the region was not the moment of Protestant women’s religious domestication, but rather an opportunity for a new type of public stewardship of the church, one that encouraged female collective action. Women expressed their piety and leadership in the church by enhancing its materiality; they gave their churches permanence and social status.

The aesthetic choices women made about church furnishing and architecture reflected their dual goals of making spaces that were suitable for worship and more homelike. Following national trends, they embraced architectural styles that reflected denominational priorities for how a worship space should be perceived by the congregation and the outside world, selecting interior décor that communicated reverence and respectability but also comfort and hospitality.[8] Even after a church building was completed, women continued to invest their time and money in renovations, decorations, and general upkeep—work that paralleled their roles as housekeepers and hostesses in their own homes. Often they received male praise for their piety-in-action in giving household chores like sewing and cleaning a public religious purpose. Ultimately, women justified this public activism in the church as both a religious duty and an acceptable extension of their domestic responsibilities.[9]

Women of color also invested time and money in church construction and furnishing. Some did so by choice for their own semi-independent churches. Others did so as enslaved workers completing projects for white women as an extension of their enslaver’s church stewardship. Enslaved female domestic labor in slaveholding households gave white women the free time to devote to church fundraising and furnishing projects, but enslaved women also often performed the most physically demanding tasks of church stewardship, with white women overseeing the work and frequently taking the credit.[10] Modern church development and a slave society were not mutually exclusive; in the Gulf South, the construction and furnishing of Protestant churches depended on both public female advocacy and enslaved female labor. All of these women deserve credit for shaping the Protestant sacred landscape of the Gulf South and ensuring the transition from temporary mission stations to established churches.

The Stewardship of Church Construction

Starting in the late 1830s but in earnest by the 1840s and 1850s, male church leaders in the Gulf South sought stability and respectability through building churches. Evangelicals transitioning from radical sects to mainstream denominations, as well as Episcopalians, wanted to establish themselves formally in the region.[11] This process was most evident in the Episcopal Church. For instance, in Louisiana in 1841, there were only three Episcopal church buildings, but by 1861, there were thirty-three. Over the same two decades, Episcopalians built twenty-seven new church buildings in Alabama and twenty-eight in Mississippi.[12] Not only did Episcopalians have the most money to spend due to the average wealth of their church members, but they were also unique among Protestants in having a doctrinal motivation for church construction. Unlike other denominations, Episcopalians required consecrated buildings that were ritually set apart from the secular world.[13] By the 1840s, Episcopal churches throughout the United States embraced a Gothic Revival in church architecture as part of the Ecclesiological Movement’s renewed emphasis on the grandeur and ceremonial significance of a consecrated church building and the rituals performed there.[14] Influenced by northern architects like Richard Upjohn and Frank Wills, Episcopalians in the Gulf South viewed medieval Gothic design elements of stone construction, pointed arches, steeply-pitched gabled roofs, and stained glass windows as ideal for consecrated sacred space. Often, however, the limited availability of materials meant adopting vernacular brick or wooden “Carpenter Gothic” alternatives (Figure 1).[15]

While averaging fewer and less expensive building projects a year than Episcopalians, Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians also began building more permanent church structures in the Gulf South in the 1840s, as a result of what Peter Williams has called “the embourgeoisement of Evangelicalism, its growing prosperity, and its endorsement of the region’s sociopolitical establishment and its values.”[16] Mainstream evangelicals invested in wood frame structures in rural regions and larger brick structures in more concentrated population centers and wealthier plantation districts. Imitating secular buildings of power like state capitols and wealthy plantation homes, many evangelicals, inspired by Greek Revival architecture, designed their churches with columned porches or porticoes topped by low-pitched pediments to resemble classical Greek temples (Figures 2–3).[17] Evangelical denominations were less concerned with the “ritualistic propriety” of having a Gothic-style church, but, responding in part to denominational competition, prioritized having more permanent and respectable physical spaces, in which their congregations could meet and worship.[18] Church building could confirm the stability and status of their denomination in the region and of the members of the congregation who funded them.

Protestant women responded to male anxieties over church legitimacy and status by acting publicly to fund these church-building projects. Women frequently appeared on subscription lists to pay building costs. The amount women donated was often higher than the average church pledge yet reflected the general scale based on the average wealth of church members by denomination. A report published in the Mississippian in 1857 estimated that Baptist and Methodist families donated on average around $3.40 a year to their churches, Presbyterian families $7, and Episcopalians $18.[19] In the 1850s, several Episcopal women subscribed $50 or $100 to build a Gothic Revival church in Napoleonville, Louisiana, designed by New York Ecclesiological Society architect Frank Wills, and one white woman, Mrs. Josephine Pugh, pledged $500.[20] That same decade, women’s building fund subscriptions at Third Presbyterian Church, New Orleans ranged from $5 to $100 to replace a small wood-frame church with an imposing brick building with a ninety-foot spire.[21] In 1854 women appear on the subscription list for Magnolia Baptist Church donating from $1 to $50 to construct their first permanent building, a wooden clapboard structure, in rural Claiborne County, Mississippi.[22] While the aesthetics of these buildings varied by geography and denomination, the consistent willingness among women to subscribe more than the average pledge to build a church reflects that they similarly saw a pressing need for their congregations to have their own church buildings.

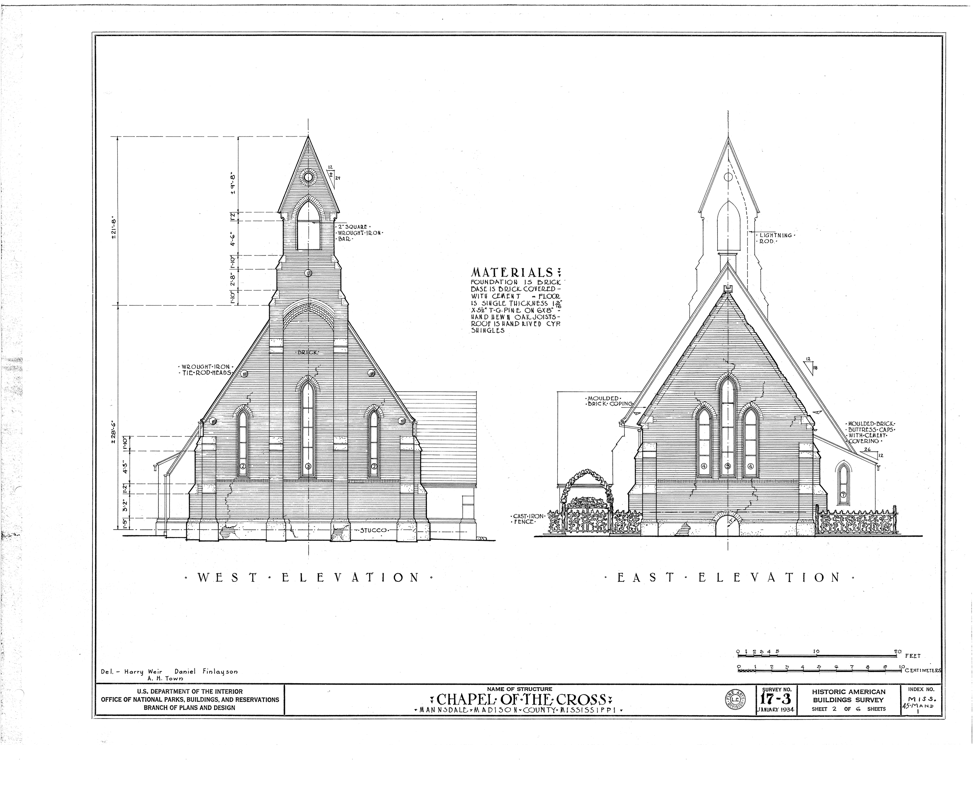

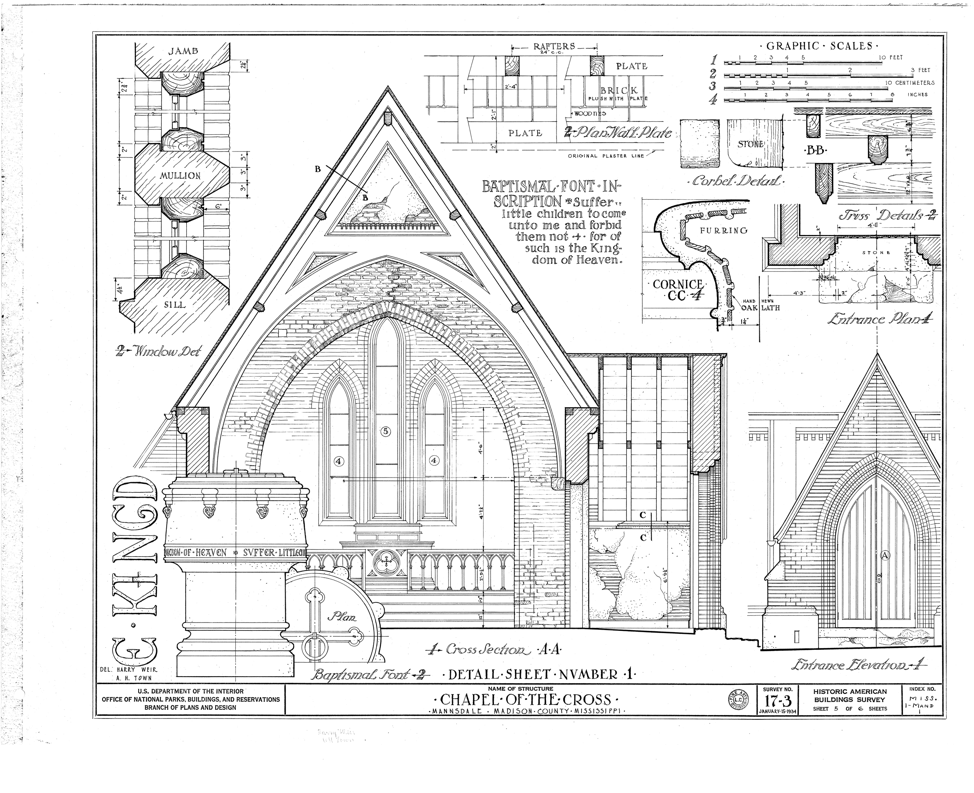

Several prominent white women served as the primary donors for their church buildings and received public praise from clergy for their “pious liberality” in making construction possible.[23] In the early 1850s, Episcopal widow Margaret Johnstone donated ten acres and funded the construction of the Chapel of the Cross in Madison County, Mississippi for her congregation, which had previously met in the non-consecrated space of a schoolhouse.[24] The Gothic Revival church, also designed by Frank Wills, had pointed arches around its windows, doors, and even the bell tower, and was made of brick covered in plaster to mimic the stone of medieval English churches (Figure 4-5).[25] Enslaved laborers made the bricks out of local river clay and harvested the interior beams and flooring from oaks growing on Margaret’s property, but Bishop William Green declared that the church was “erected by Margaret,” reducing the enslaved laborers to an extension of her activism.[26] According to Bishop Green, the Chapel of the Cross was “one of the most beautiful structures of the Church kind to be found in any of our Southern or Western Dioceses” and “seemed deeply to impress” all those who attended the consecration service.[27] Female financial patronage of church construction took on public religious significance as the means of solidifying church presence and status in the region.

The importance of having a separate sacred space for worship also motivated Episcopal slaveholding women to construct chapels on their plantations for the enslaved at a higher rate than other Protestants.[28] While the physical construction of these chapels was certainly performed by enslaved laborers, white women received the sole credit from their priests for being “a mistress sensible of her responsibility” in building this space to facilitate the mission to the enslaved.[29] In 1861 Louisa Harrison, widowed owner of Faunsdale Plantation in Marengo County, Alabama, requested and received an official consecration of her chapel from her bishop, “separating it henceforth from all unhallowed, ordinary and common uses.”[30] Descriptions of the chapel have not survived, but, given its intended audience, it was certainly not as large or expensive as St. Michael’s—the Gothic Revival church with medieval castle-style turret where Harrison herself was a member.[31] Having a visually pleasing chapel for the enslaved, however, could serve as a status marker to impress her white neighbors, and as a physical symbol of her Christian benevolence as a slaveholder.[32] It is likely the chapel more closely resembled the wooden “Carpenter Gothic” cabins where enslaved laborers lived, some of which have survived to this day (Figure 6). For Harrison, an Episcopalian, it was not sufficient to declare this chapel a sacred space herself; she needed the recognition of a public authority—the head of her diocese—to deem the space to be sacred, blurring the line between public and private religious space on the plantation.

In addition to giving their own money or property, Episcopal white women in the Gulf South also led the way in collecting subscriptions for church construction.[33] In 1858 Francis Hanson, rector of St. John’s-in-the-Prairie of Green County, Alabama, reported that Ann Paine Avery, the widow of the church’s first rector, John Avery, and her daughters “have taken charge of the business and promise to raise funds and have the church built.”[34] Hanson praised the female members of this family for the small but still “beautiful and substantial” board-and-batten Carpenter Gothic building they funded, designed by Richard Upjohn, the New York architect who made Carpenter Gothic popular in America (Figure 7).[35] Jane Dalton, another Episcopalian, was the principal fundraiser for two different church-building projects in the Gulf South, first in 1845 in Livingston, Alabama where she was declared her church’s “chief founder,” and then again in Aberdeen, Mississippi in the 1850s where she raised almost $3,000 for building costs.[36] Bishop William Green praised Dalton’s “noble zeal” and “self-sacrificing labors” to raise these funds and her rector, J.H. Ingraham, commended the five or six other churchwomen who, “prompted by pious zeal,” assisted her and raised over $1,000 in subscriptions to start construction.[37] According to Ingraham, the town of Aberdeen was “under the religious influence of Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists” with the few Episcopalians “almost lost” to evangelical influence.[38] Thanks to these women, however, they “purchased a lot in the most beautiful part of town” and built an impressive brick Gothic Revival structure.[39] Resembling a medieval castle, it had a seventy-foot central tower topped with four turrets and crenellations along the entire roofline.[40] Although Dalton died before seeing the finished building, the congregation placed a memorial tablet in the church, which Bishop Green declared would “meet the view of each worshipper in that beautiful temple to tell them of the good done unto the House of God by Mrs. Jane M. Dalton.”[41] With this memorial tablet, Dalton effectively became part of the sacred space she helped create, with her public identity as “church builder” built into the structure that was responsible for solidifying the Episcopal Church’s prominent status and permanence in Aberdeen.

White evangelical women also served as subscription collectors and received praise from their ministers for being “instrumental” in making church construction happen.[42] First Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi recognized Sarah, the wife of the Reverend Lewis B. Holloway, as the leading fundraiser for their first church built in 1844.[43] From its founding in 1838 to 1844, the congregation had no permanent meeting space and had to rotate between members’ homes.[44] With Mrs. Holloway’s fundraising, a new brick church was built in the Greek Revival style with a front façade, which resembled an elite plantation home. It had a prominent central staircase and a distyle in antis porch—two Doric columns in the middle and Doric pilasters on its sidewalls, which extended to the front of the porch.[45] The congregation still maintained the traditional evangelical double entrances, however, one for women and one for men, that corresponded to separate seating and emphasized church sisterhood and brotherhood identities over one’s social status or family identity.[46] While the church preserved this element of its more radical evangelical past, it embraced the overall architecture of mainstream secular institutions of power.

Raising subscriptions for church construction in the Gulf South was not exclusive to white women. Betsy Crissman, a free woman of color who ran a boarding house in Jackson, Mississippi in the 1850s, used her connections in the urban, free black community to collect money to build several black Protestant churches in town. While no material evidence of her actions remains, Crissman described her efforts in an interview in 1866. As she explained, before she got involved, “we had to take boards for seats and go into the graveyard, rain or shine, cold or wind.”[47] Crissman heard from a visitor staying at her boarding house that “colored folks had churches in other places, and I determined we would have one also, and set to work immediately.”[48] She figured out how many men and women in her community could pay at least a dollar towards building a church. Then, she found a white man to write up a subscription paper for her, which she carried around to all her potential donors.[49] Crissman did not stop there, claiming that she helped “put all I could into their treasuries, until every [church] house was finished, five in number.”[50]

Crissman’s actions exemplify what Sylvia Frey and Betty Wood in Come Shouting to Zion have described as efforts among antebellum black Americans to “express their sense of community, their sense of self-worth, and their sense of self-respect” through how they used their resources of time and money to build churches independent from white religious communities.[51] Not only did Crissman fund the “permanent physical symbols of common held beliefs and values, of a shared purpose and commitment,” but she also claimed greater visibility and social status for herself within her community by doing so.[52] While Frey and Wood have found evidence of this female church stewardship in Antigua and Savannah before 1830, Crissman stands out as a late antebellum example of this work in the Gulf South, building churches in the face of increasing crackdowns on independent black churches after Nat Turner’s 1831 Rebellion.[53] Certainly having connections within the free black community and patronage of a white male helped her cause. However, Betsy Crissman took it upon herself to go out and raise the money. While there is no record of what these buildings looked like, her actions indicate that she valued having permanent spaces where black religious communities could gather and worship regardless of the weather, a priority she shared with white women in the region and which was essential to ensuring the construction of antebellum churches across the Gulf South.

Churchwomen and Collective Fundraising

Protestant women in the Gulf South were also more likely than their male counterparts to act cooperatively, working with other women to raise money for church building projects. Some women coordinated subscription collecting and letter writing campaigns to potential donors, while others organized fundraisers.[54] Giving new outward-facing religious significance to a domestic chore, churchwomen started sewing groups that took in work from the community or sold sewing projects at fairs and donated the profits to the church. White women across class and regional divides in antebellum America were expected to know how to sew, as household thrift and industry were crucial to the domestic ideal of the “cult of True Womanhood.”[55] Young girls learned needlework from older family members and, for those who could afford to attend, female academies continued to teach ornamental sewing and embroidery throughout the nineteenth century.[56] Sewing was also already a communal activity; women often sewed together with other women in their family.[57] The church sewing society expanded this communal household activity to include women connected by their church, who would meet in one another’s homes for the public religious purpose of supporting church construction. This communal sewing fell within the sphere of acceptable women’s work.

For slaveholding women, however, enslaved women did most of the domestic sewing for their family and the enslaved laborers working on their property, with white women distributing supplies, cutting out patterns, and overseeing the work.[58] Enslaved workers also performed most of the labor leading up to sewing projects, especially when using cotton or wool produced on the plantation. They grew, picked, and cleaned the cotton, sheered animals and carded the wool, spun thread, and wove and dyed cloth, as well actually assembling clothes, blankets, and other textiles for the household.[59] With enslaved women completing everyday sewing projects, slaveholding white women had the leisure time to devote to special sewing projects for their sewing society, and, even then, relied on enslaved women to assist in their completion.[60] Enslaved labor made southern white women’s church sewing societies possible.

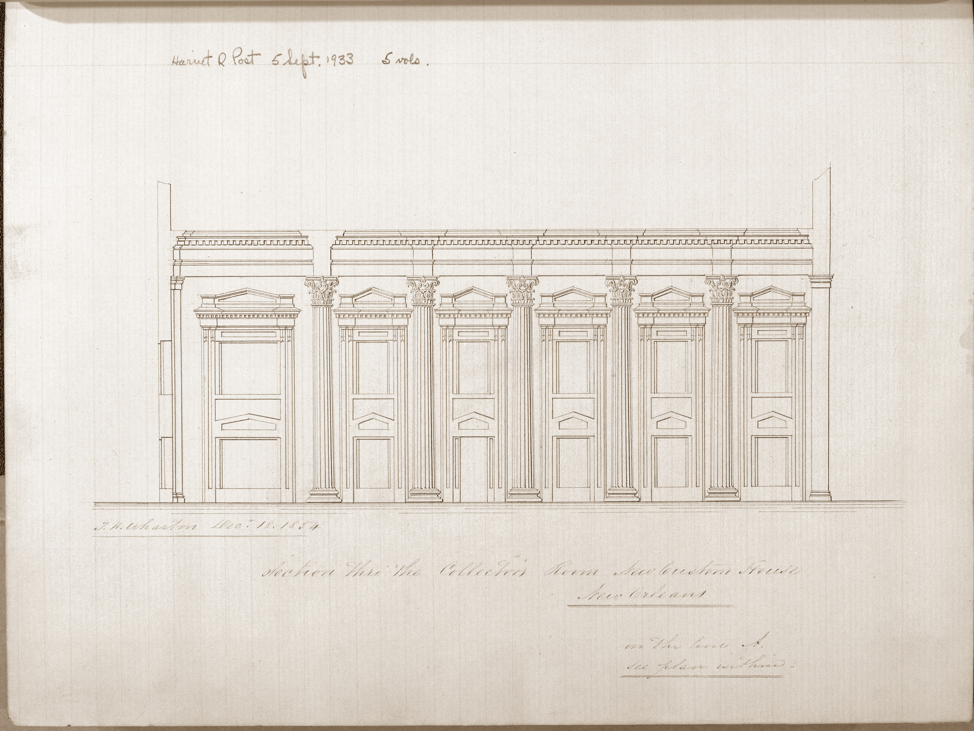

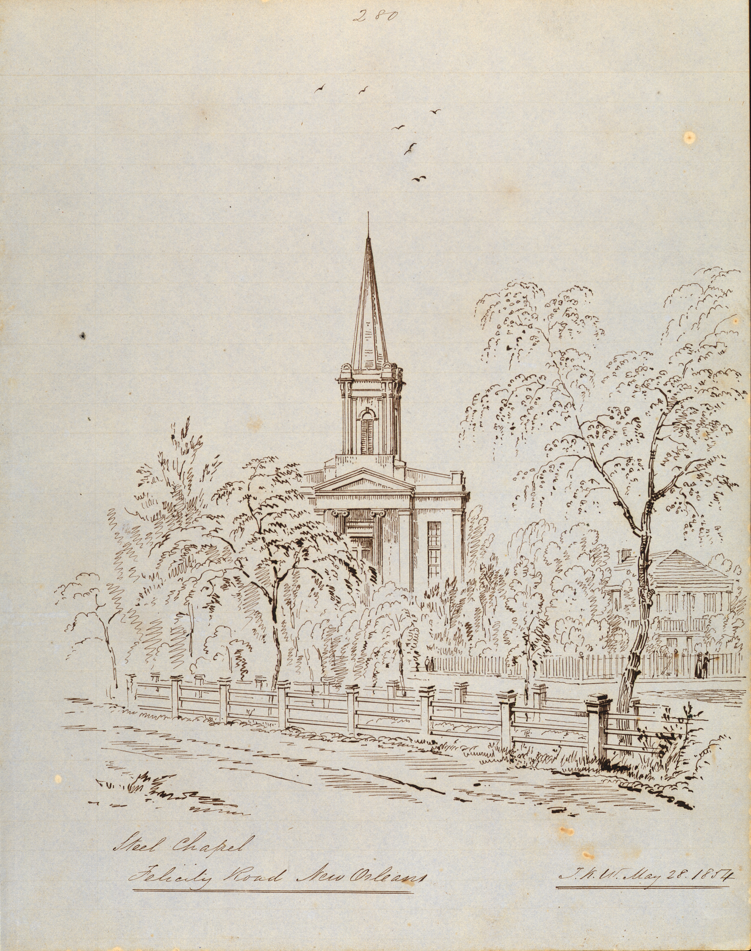

Protestant “ladies’ fairs,” where white women ran booths to sell items made in their sewing societies alongside refreshments and entertainment, were routine events in the antebellum Gulf South. While especially popular in antebellum cities like New Orleans, Mobile, Natchez, and Vicksburg, women also held church aid fairs in smaller towns across the region including Pass Christian, Mississippi, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, as well as in rural outposts like Thibodaux in southern Louisiana, Wahalak and Salem in Mississippi, and the Alabama Black Belt plantation districts—a region named for its dark, fertile soil.[61] The fairs held in cities had the largest turnout and raised the most money. When Methodist ministers struggled to raise funds by subscription to build the Elijah Steele Chapel in New Orleans, the Methodist Ladies’ Sewing Society of the congregation advertised two fairs in 1848, which raised enough money to buy a city lot, in addition to nearly $1,000 to pay for church construction.[62] Designed by Thomas K. Wharton, the same Greek Revival architect who would design part of the U.S. Customs House in New Orleans, Steele Chapel had a Greek temple-style façade with Ionic columns and Doric pilasters on the portico, topped with a columned bell tower and an impressive spire that added to the skyline of New Orleans (Figure 8–9).[63] The church also had only one front door and family pew seating which, like the architectural style, were material indicators of a denominational shift towards acknowledging family and social status over more radical evangelical ideals of Christian sisterhood and brotherhood. The Ladies’ Sewing Society made this architectural marker of status possible.

Some sewing societies also donated the proceeds of their fairs to women of neighboring congregations, connecting female networks to support denominational growth throughout the region. Jane Copes in Vicksburg, her sister-in-law Mary Ann Copes in Jackson, and Mary’s sister-in-law Hester Alsworth in Canton, Mississippi were responsible for coordinating their respective sewing societies to help each other’s put on fairs to fund the construction of Presbyterian churches in the 1840s. In 1843 and 1844, Jane regularly wrote to Mary asking her what clothing items they still needed for the Jackson fair and, when she could not attend the fair herself, asked Mary to “let us know what sells best so that we may prepare the most useful things again.”[64] With help from the Vicksburg sewing society, Presbyterians in Jackson, who had previously met in the Greek Revival-style Mississippi State Capitol, built a brick Greek Revival Church using the same architect and mason responsible for the Capitol Building.[65] A desire to imitate the Greek temple-like façade of the most powerful political building in the city is clear. The Presbyterian sewing society of Jackson then donated items to Canton, Mississippi’s Presbyterian sewing society for their fair to build their own brick church with Greek Revival features.[66] These women were connected by family ties. However, they also acted as representatives of their sewing societies, working collectively to employ a domestic chore like sewing for a public religious need. In doing so, they funded the construction of respectable churches across the region.

White women also fundraised by organizing suppers and concerts.[67] The Ladies Working Society of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Columbus, Mississippi held a concert in 1859 to pay off the debts on their new church building.[68] They helped replace a simple wood frame structure built in 1838 with a larger brick Gothic Revival Church with pointed-arch windows, stone-topped spires, and a crenellated bell tower and roofline.[69] In 1849 in the Alabama Black Belt town of Demopolis, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal women each hosted their own church benefit supper, and residents across denominations were invited to attend all three.[70] Protestant women shared fundraising methods that were based on women’s already existing domestic responsibilities. As with sewing, cooking and hosting were crucial elements of the ideal of women’s domestic identity in nineteenth-century America, even as most slaveholding women relied on enslaved women to prepare and serve meals in their own homes. This enslaved labor gave elite southern women the time to prepare special desserts for fairs and suppers. Slaveholding women certainly also relied on enslaved women to complete many of the physically demanding tasks like hauling supplies, cooking, and cleaning at their fundraiser events, as they did when hosting guests in their own homes.[71] Here too, just as slaveholding men claimed to plow fields or sew crops in their letters and diaries, white women claimed these domestic labors as their own, or insisted on their crucial role as household managers who made sure these tasks were completed.[72] All of this labor performed by enslaved women to make fundraising fairs, suppers, and concerts happen, labor often silenced in white accounts, was co-opted as an extension of slaveholding women’s church stewardship. Management of enslaved household labor, then, was a form of white female religious activism in the South that both confirmed a slaveholding version of the domestic ideal and made funding church construction possible.

From 1830 to 1861, the Gulf South saw at least twenty-six official white female church aid societies tied to Episcopal Churches, fourteen Baptist female societies, nine Presbyterian, and six Methodist.[73] While having the smallest number surviving in historical records, some of these Methodist societies were multi-church organizations that drew their membership from across the region.[74] These named female societies were all in addition to the many more informal groups of “church ladies” who met and worked together for similar purposes, despite the lack of title in the mostly male-authored surviving records. All of these organizations are proof that it did not take the Civil War for white southern women to create separate female church associations and sewing societies—they did so well before, and in fact, often relied on enslaved labor to fundraise for the construction and furnishing of modern sacred spaces.

While white women fundraised for church construction all over the Gulf South, cities like Mobile and New Orleans which had more concentrated free black populations offered unique opportunities for women of color to raise money for their own churches. New Orleans’s Daily Picayune in March of 1854 and December of 1856 included advertisements for fairs “given by the ladies of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, for the purpose of extinguishing the debt on the edifice” of St. James Church.[75] This free black congregation separated from the white congregation of St Paul’s Methodist Church in 1848 when the church ruled that all black members must sit in the balcony.[76] In February and May of 1855, the Daily Picayune advertised two other fairs “held by the colored ladies of New Orleans” that were “for the Benefit of the Fourth Colored Baptist Church.”[77] In Mobile, female members of the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd, a black congregation with a white priest, ran a fair in 1860 to raise money to build a new church in a “more favorable location” in town.[78] Most likely many of the free and enslaved women who sewed items and prepared and served food for these fairs already worked as domestic laborers or seamstresses in Mobile and New Orleans.[79] With these fundraisers, black churchwomen turned the work that was usually performed for the benefit of whites into labor for the benefit of their own religious communities, a subversive act in a slave society.[80] By fundraising like white women through the domestic work of sewing, cooking, and hosting, these women of color were also able to claim respectability by working within white standards of acceptable female labor.

It is striking that black women in both cities were able to organize such public events with the white approval necessary to advertise in newspapers and, as was the case in Mobile, to receive recognition from a white priest who recorded their actions in his report to the Diocese of Alabama.[81] Although there is no evidence that black Protestant women formed official church aid societies in the Gulf South, their fairs exemplify that they, like their white counterparts, found female religious community through collective stewardship, which remained acceptable even after the backlash against black churches following Nat Turner’s Rebellion.

There is also evidence that some free women of color physically labored to construct their churches, as was the case at St. James AME in New Orleans. When the free black congregants first left St. Paul’s Church, they met in a temporary building next to a blacksmith shop owned by one of their members.[82] From 1848 to 1851, the congregation donated their own labor to build a brick church in the “late Greek Revival” style, which had elements of both classical and Gothic architecture.[83] Its façade, with four pilasters supporting a classical pediment, was a simplified version of the respectable white Methodist churches in New Orleans like Steel Chapel.[84] Whilemale members completed most of the carpentry and masonry work, women, who represented sixty-three percent of the membership in 1848, transported the building materials around the construction site, reportedly carrying bricks in their arms and aprons.[85] Forced enslaved labor was certainly responsible for much of the physical construction of white and biracial churches in the Gulf South, but the female labor offered by free women of color at St. James AME was voluntary. In addition to fundraising, these women made the choice to contribute their physical labor, indicating the priority they placed on having independent sacred spaces that also embraced white evangelical standards of respectable church architecture.

The Stewardship of Interior Furnishing

Protestants in the Gulf South also relied on churchwomen to donate and to fundraise in order to furnish the interiors of these new churches with appropriate furniture, musical instruments, and décor. As with their own homes, white women had much more influence on the aesthetics of furnishing interiors than the architecture of the buildings themselves, which were designed by male architects to meet denominational standards of respectability. While furnishings still needed to comply with the denominational needs for worship, individual women and female church aid societies were often responsible for deciding on the specific purchases or making items by hand. Their priorities about what their worship spaces needed and how they should look and sound during a service shaped the material culture of their churches.

As with furnishing their own homes, middle and upper-class Protestant white women prioritized church furnishings that imbued social status, comfort, and hospitality.[86] Like their northern and eastern counterparts, Gulf South women embraced a national trend in antebellum Protestant denominations to make churches feel more welcoming and homelike in order to nurture a religious community or “church family” and to foster an emotionally fulfilling worship experience.[87] In 1854 a Methodist minister in Pattersonville, Louisiana reported that the women of his church “will carpet the altar, mat the aisle, and whitewash the inside of the church; purchase lamps, and improve the seats. This is all the house needs to make it comfortable.”[88] Other women purchased more modern comforts like stoves to keep their churches warm during the winter months. Presbyterian Jane Copes in Brookhaven, Mississippi determined the type of stove and amount of exhaust piping her church needed and entrusted her sister-in-law in New Orleans with picking out one that met her specifications and budget.[89] Protestant women throughout the Gulf South purchased and installed curtains and carpets and replaced backless benches with more comfortable chairs and cushioned pews.[90] Some women’s organizations, like the sewing society of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Carlowville, Alabama, used “the proceeds of their handiwork” to purchase textiles like new carpets, while others furnished their churches with textiles they made themselves.[91] Churchwomen made the carpet for St. John’s Episcopal Church in Montgomery and the Episcopal sewing societies in Columbus and Canton, Mississippi made the seat cushions for their churches’ pews by hand.[92] As the rector of Grace Church in Canton reported “the ladies have been busily employed several days, cushioning the seats and otherwise adding to the comfort of the church.”[93] Ministers also prioritized comfortable worship spaces and looked to the women of the church to expand upon their domestic roles as seamstresses and hostesses to buy, make, and install furnishings that would achieve this goal.

Again, white slaveholding women often took credit for the physical labor performed by enslaved women to furnish their churches. In Jefferson County, Mississippi, for instance, Olivia Dunbar brought enslaved women Serena, Lavinia, and Annica to Church Hill Episcopal Church to assist the sewing society in making carpets for the nave and chancel.[94] While enslaved men were certainly responsible for much of the exterior church construction, it was these enslaved women who performed the manual labor of furnishing the interior. Unlike the women who labored to build St. James AME in New Orleans, their labors were not for their own religious community or by choice. There is no evidence that Serena, Lavinia, or Annica ever attended Sunday services at the church, and yet they performed the necessary labor to make this church comfortable and respectable before the bishop visited that spring.[95] At the same time, in a society that valued slaveholding social status, employing enslaved labor elevated the space of the church as it did the home of a slaveholder, and provided status to the white women who oversaw this work instead of performing it themselves. In the process, slaveholding women effectively expanded the space of their domestic managerial duties to include the public space of the church.

In addition to making church interiors welcoming and comfortable, Episcopal women purchased expensive furnishings that would elevate their consecrated spaces, inspiring awe and reverence during the service while also highlighting the prosperity of the donors and the church itself. In 1840 William Crane, rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Woodville, Mississippi, credited “the zeal and industry of the ladies composing the sewing society” for raising funds and purchasing chairs, carpets, and a “handsome cut glass chandelier.”[96] The money Jane Dalton and her sewing society raised for St. John’s Episcopal Church in Aberdeen, Mississippi helped pay for painting the interior “in imitation of English oak” to resemble medieval churches and adding columns and railings that were “richly bronzed.”[97] They ensured that the interior of the church was just as impressive as its brick Gothic Revival exterior.

Women also used impressive furnishings to highlight important ritual spaces within their churches. Women from denominations that practiced “sprinkling” baptisms purchased carved stone baptismal fonts that were used to perform this important sacrament to initiate church members.[98] Margaret Johnstone paid for an imported stone font for her Chapel of the Cross that was shipped from Italy to Mississippi in three parts (Figure 10).[99] Reflecting a shared Protestant emphasis on the importance of preaching and Bible reading during the service, white women in all four mainstream denominations in the Gulf South decorated their pulpits and reading desks. Some purchased “pulpit hangings” or pulpit “curtains,” cloth decoration that was often embroidered, while others, like the women of Five Points Baptist Church in Midway, Alabama used their domestic sewing skills to make these adornments by hand and received the thanks of the congregation in the church meeting minutes “for dressing the Pulpit.”[100] In 1857 Presbyterian Jane Copes handmade a book cushion for the pulpit Bible used at the new Presbyterian Church in Brookhaven, Mississippi.[101] Others purchased special Bibles and prayer books for ministers to use during the service, including one woman at the Episcopal Church of the Advent in Adams County, Mississippi who, according to Deacon John Philson, “presented the Church with a richly bound quarto Prayer Book for the Desk.”[102] While their bodies were physically excluded from these sacred spaces during worship, being denied the right to baptize or preach on the basis on their sex, women claimed public visibility through their furnishing work, purchasing or making items that distinguished important ritual spaces within their churches.

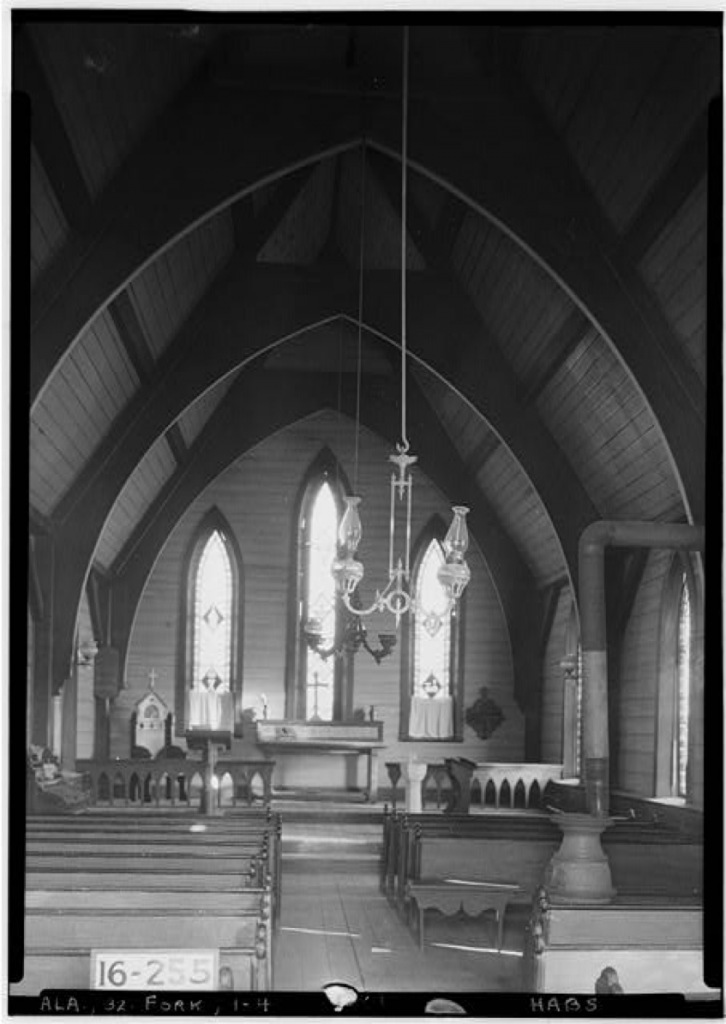

For Episcopalians, the most important space to furnish was the chancel, where the altar resided and where ordained clergy sat during the service and performed the Eucharist.[103] Often the chancel was separated from the body of the church by a railing, like at the Chapel of the Cross and St. John’s-in-the-Prairie which had pointed-arch railings that mimicked the pointed-arch ceilings, windows, and doorways of the Gothic Revival architecture (Figure 10–11). The white women of the Avery family also raised funds to put stained glass windows in the chancel of St. John’s including one inscribed with the name of John Avery, the family patriarch and the church’s original rector.[104] Motivated by a desire to honor a deceased family member, they chose a memorial that fit with Episcopal furnishing aesthetics of the nineteenth century. Stained glass windows were especially popular in medieval churches and Episcopal women in the Gulf South used them like Gothic architectural elements to signal a return to the awe-inspiring aesthetics of medieval sacred spaces.[105] In 1861 Mary Ann Cruse used the money she made writing Betsy Melville—a prescriptive novel about an Episcopalian who grows up to become a missionary wife—to pay for the central stained glass window to honor of her deceased brother in the new Gothic Revival Church of the Nativity in Huntsville, Alabama.[106] These women used chancel windows to elevate their families and their churches. Other women worked collectively to purchase chancel windows.[107] In her sketch of Trinity Episcopal, Pass Christian, Margaret Savage chose to focus on the chancel side of the church, highlighting the central stained-glass window with pointed-arch and floral cross woodcarvings that separated its panels, which was funded by her church sewing society (Figure 1). These women chose to furnish their churches with chancel windows because of the ritual and liturgical significance of the space around the altar, which held the attention of the congregation for most of the service.

Whitewomen purchased walnut and mahogany altar tables and matching chairs for their clergy, often designed by craftsmen in New Orleans or cities on the East Coast, with the same care they gave to decorating a dining room before guests arrived for dinner.[108] Before services with communion, they dressed the altar tables with embroidered cloths and silver candlesticks.[109] Rather than donating individual communion plates and chalices, as was common in Episcopal churches in the eighteenth century, antebellum women increasingly pooled their money to buy matching “communion services,” the same way many nineteenth-century Americans sought matching dishware for entertaining at home.[110] Reflecting the importance of the ritual meal of communion in Presbyterian Churches, white Presbyterian women in the Gulf South worked together to purchase communion services for their churches as well.[111] On at least seventeen occasions from 1839 to 1861 with the majority in Episcopal churches, Protestant women in the Gulf South purchased communion services for their churches, often receiving praise for raising enough money to afford ones made entirely of silver. Their purchases reflected highly on the status of both the church and its female patrons, as well as on the importance that the community placed on the ritual of communion itself.[112] On one occasion, enslaved women in Adams County, Mississippi contributed money to purchase what the bishop called a “handsome” communion set, following white furnishing standards and claiming respectability for themselves and their congregation in the process.[113] In an increasingly home-like church interior, the chancel was the dining room, and women its caretakers and hostesses.

The importance of Episcopal Church chancel décor was heightened on high holy days like Christmas, when white women “dressed” their churches with evergreens, lanterns, and banners in order to adorn the worship space.[114] In her 1854 children’s book, The Little Episcopalian, Mary Ann Cruse of Huntsville, Alabama portrays a conversation between a female Sunday school teacher and the book’s protagonist, in which the teacher explains to the main character why women decorate their church at Christmas. Connecting the act to women’s domestic duties to decorate their homes for special occasions, the student recounts that: “it is Jesus Christ’s birthday, and my Sunday school teacher says, that as the church is Jesus Christ’s house, it is very proper to decorate it on his birthday.”[115] According to Episcopalian Emily Douglas, the women of the Church of the Epiphany in New Iberia, Louisiana went so far as to prioritize dressing the church for Christmas over actually attending Christmas services. In 1858 “as Christmas came near the ladies of the congregation met to decorate the little church but most of them living so far away nine or ten miles, very few were able to celebrate Christ’s birth by their presence at church.”[116] Women like Emma Balfour of Vicksburg took great pride in being asked to direct the other churchwomen in dressing the church for Christmas, reporting to her sister-in-law, Louisa Harrison, that Bishop William Green and her rector Stephen Patterson praised their work, both priests declaring that they had “never seen a church so beautifully decorated.”[117] According to Balfour, Patterson also went on to compliment the women on their sense of religious duty, women who would put on hold their domestic duties around the season—“who would neglect their own concerns, the concerns of the world to decorate the house of God.”[118]

Leigh Schmidt connects the rise in church holiday decorations in Episcopal Churches to the Gothic Revival, arguing that the mid-nineteenth century witnessed “a new aesthetic of church adornment, nostalgically medieval and Gothic in its vision, but decidedly Victorian and modern in its elaboration.”[119]In The Little Episcopalian, women decorated their church extensively with wreaths and garlands, hanging a “star in the East,” as well as a banner that read “Christ our Righteousness” over the pulpit as a reminder of the devotional significance of the decorations.[120] The excess of decorations is certainly evident in the Christmas dressings in Mobile’s Christ Church in 1841, which had a long record of female stewardship (Figure 12).[121] While garlands covered the balconies, most of the decorations were used to highlight the chancel space, with matching wreaths on both sides of the altarpiece, matching greenery draping the pulpit and reading desk on either side of the altar, and elaborate evergreen arches and latticework above garlanded chancel columns, all of which directed attention to the altar table. Sewn into the altar cloth were devotional phrases that read “The Life,” and “Do This In Remembrance of Me,” reminding Episcopalians of the liturgy of the Eucharist performed on the altar. As an addition to the permanent devotional wording at the top of the altarpiece, “Reverence My Sanctuary,” which reminded worshippers that the church was a consecrated sacred space deserving of admiration all year, decorators attached a Christmas banner that read “Bethlehem!” and a large star, symbolizing the star that led the three Magi to where Jesus was born. It is likely that these decorations were hung with the help of enslaved labor employed by the wealthy slaveholding women who ran the sewing society. The decorations were meant not only to adorn the chancel space and the ritual of Eucharist, but also to connect it to the sacred space of Jesus’s birthplace. While the Christmas tree, which gained popularity in America in the 1840s and 1850s, was the centerpiece of women’s Christmas decorations in their own homes, in Mobile’s Christ Church the tree was small and off to the side, appearing to be more of an afterthought than a central part of the decorated chancel’s main display.[122]

Episcopal women also performed the ritual acts of “stripping” the chancel of Christmas decorations on Ash Wednesday to prepare the worship space for the more solemn liturgical season of Lent and re-decorating the chancel with flowers for the Easter season.[123] Flower gardening was already considered an acceptable domestic hobby for white women in the antebellum South. Protestant women throughout the region grew flowers to decorate their tables at home, as well as tables for church fundraising fairs and suppers.[124] Episcopal churchwomen, however, also used flowers for their religious symbolism, associating them with resurrection and new life in springtime after the Lenten winter.[125] When the women of St. Andrew’s Church in rural Macon County, Alabama decorated the chancel with Easter flowers, their rector Francis Hanson wrote of the flowers, “I trust their beauty and fragrance inspired all our hearts with a deeper feeling of love and gratitude to God for all His mercy and goodness to us.”[126] Hanson recognized that the labor women performed in decorating the church was, in fact, religious work, ensuring that the consecrated space would appeal to all of the senses and inspire emotional, reverential responses to the worship service, particularly on the holiest days of the church calendar.

Women across all four mainstream Protestant denominations in the Gulf South purchased musical instruments to help create a worship environment every week that would inspire emotional, reverential responses. For the church exterior, women purchased bells and bell towers, which also made for more impressive church façades.[127] At St. John’s Episcopal Church in Tuscumbia, Alabama, one woman in 1854 furnished the new Carpenter Gothic bell tower with a “a good-toned bell, weighing 350 pounds” (Figure 13).[128] Exterior bells also played an important practical role in announcing service times to the community. Jane Copes used her contacts in Jackson, Mississippi to select a bell for her church in Brookhaven after reporting to her brother that “we have plenty preaching, but the people do not attend as they should—hence the need of a bell.”[129] Women prioritized bells in poorer rural churches as well. For instance in 1842, Maria Lide sung in a choir concert to help her Baptist church in rural Alabama purchase one.[130] In addition to being a publicly visible symbol of social status, these bells also served to welcome new members to church services and increase the aural presence of the church on Sunday.

Instruments inside the church added to the power and spectacle of music during the service and served as markers of social status. By including detailed descriptions in their annual reports to their dioceses that were meant to impress other church leaders, the rector of the Episcopal Church of the Nativity in Rosedale, Louisiana reported that a churchwoman had donated “an organ of ten stops and one octave of pedals, built by Pilcher of St. Louis,” and the rector of St. Luke’s in Jacksonville, Alabama reported that “a zealous lady of the Parish has presented our Church a beautiful Harmonium a Percussion of exquisite workmanship, with twelve stops, manufactured by Messrs. Alexandre & Son, Paris,” France.[131] In the process clergy also awarded public visibility and status to the churchwomen who funded them, even when these female patrons went unnamed in reports. From the late 1830s to 1861, male-authored church records in the Gulf South thanked women for adding eleven organs, seven bell sets, four melodeons, and one harmonium to their churches, with women from wealthier and urban congregations paying $400 to $1,000 for “a handsome and finely toned organ.”[132] As with other furnishings, church instruments proved to be investments with both social and sacred value.

Stewardship of Church Maintenance and Housekeeping

Even after church construction was complete, white women continued to look after the physical needs of their buildings, often taking the lead in maintenance projects, especially if it involved tasks transferrable from domestic duties like cleaning. In 1861, Methodist Myra Cox Smith of Greenville, Mississippi wrote in her diary that, “for two days past I have exerted every physical power to its utmost putting our little church in order.”[133] Although physically exhausting, Smith found the work spiritually rewarding. While she was working in the church, she wrote that

there came the feeling that it was God’s house and how blessed to be permitted to come there and work. Just then, as though God would reward me for it, a flood of love and joy poured into my soul. My Savior drew very near to me. ‘Glory be to God’ involuntarily escaped from my lips.[134]

Smith interpreted the physical labor she performed to clean the church as religious duty, quoting Psalm 84 and declaring, “How truly can I say, I would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God than to dwell in the tents of wickedness.”[135] In the 1850s at the Methodist church in Macon, Mississippi, Maria Dyer Davies recorded going to help other women sweep the church; clean the windows; and arrange the seats, carpets, and lamps.[136] All of their cleaning was voluntary and unpaid, but still deemed acceptable because of its association with female domestic labor.

As with furnishing the church, however, slaveholding white women also relied heavily on the labor of enslaved women—not just enslaved men—to complete some of the more physically demanding tasks. In 1846, at Church Hill Episcopal Church in the plantation-rich Jefferson County, Mississippi, Eliza Magruder and her aunt Olivia Dunbar supervised their enslaved female laborers Serena, Livinia, and Nancy who “scoured” the church before a bishop visit.[137] While non-slaveholding women at Five Points Baptist Church in Midway, Alabama raised money to pay laborers to clean their church graveyard, Episcopal women in Church Hill oversaw enslaved women who cleared the churchyard of tree debris and mowed.[138] As Thavolia Glymph has argued, “In the South . . . no white woman of any standing, nor who hoped to have any, did her own housework,” and in wealthy parishes like Christ Church Episcopal, women publicly enacted their social status by overseeing enslaved labor to clean the church house.[139] Forced female labor and religious duty went hand in hand in the maintenance of modern churches in a slave society.

For larger repair work and improvements to church buildings, white women also raised funds to pay men to do the work and to supervise enslaved laborers. Baptist women in Jackson held a two-day fair in 1859 to pay for church repairs; Presbyterian women in Lexington, Mississippi raised funds to repaint the inside of their church in 1849; and the Episcopal sewing society of St. James in Baton Rouge funded repairs to their wooden frame church after a tornado hit the town in 1846.[140] As for new improvements, white women were responsible for fundraising for the expansions of Presbyterian churches in Tuscaloosa and Selma to meet the growing size of their congregations, and paved roads and a cistern for Third Presbyterian Church, New Orleans.[141] Even in rural regions of the Gulf South women were often more successful than men in raising funds for such projects. In 1851, when St. Paul’s Episcopal Church near Greensboro, Alabama wanted to erect a new church steeple they received $200 from the women’s church aid society and only $26.15 from the rest of the congregation.[142] Women throughout the Gulf South prioritized the maintenance and improvement of their churches, taking pride in their labors to elevate and modernize their worship spaces as well as adapt them to the needs of growing congregations.

In the 1840s and 1850s, white women were especially active in funding the construction of parsonages or rectories—living spaces provided for a minister and his family. As part of the transition in the Gulf South from missionary outposts to mainstream churches, male church leaders urged their congregations to build parsonages as a way to solidify the church’s presence in the region by ensuring the physical presence of its ministers.[143] Churchwomen responded by donating, collecting subscriptions, and fundraising to build structures that reflected the social status and architectural styles of their churches.[144] In 1848 in Demopolis, Alabama, Methodist women held a “strawberry party” to pay off the debt on their “little porticoed parsonage,” which mimicked the Greek Revival columned-porch façade found in elite planter homes and modern evangelical churches (Figure 14).[145] After funding the construction of the brick Gothic Revival Chapel of the Cross in Mississippi, Episcopalian Margaret Johnstone funded construction of a rectory in what the architect referred to as a “Rural Cottage Gothic” style to match the church.[146] Women also worked to repair and modernize parsonages. In 1858 the Methodist Female Financial Association of Fayette Circuit, Mississippi repaired their parsonage, which ministers G.F. Thompson and W.B. Johnson reported “had become old and uncomfortable” and “would soon have become uninhabitable” without their efforts. Treating their efforts as work of religious importance looked on with divine favor, Thompson and Johnson wrote “May the Lord abundantly reward these good ladies for their labors of love.”[147]

As with worship spaces, some women focused on furnishing needs, like the Methodist female “Parsonage Society” of Columbus Station, Mississippi, formed “to keep the Parsonage supplied with such articles of household and kitchen furniture, crockery, &c, as are necessary for the comfort of the Preacher in charge and his family.”[148] In a less official capacity, white Episcopal and Presbyterian women in the 1840s and 1850s in Tuscaloosa and rural Lowndes County, Alabama, as well as more urban Columbus and Jackson, Mississippi, purchased household items, donated furniture, and cleaned and decorated parsonages for their rectors.[149] If these parsonages were truly to be “homes” and not just temporary residences, they needed housekeeping help from Protestant women. As the Reverend W.P. Barton of Yazoo City declared, “None but the hands of kind ladies could arrange things so. Such taste, comfort and neatness . . . our church is as neat and clean as a ladies parlor.”[150] Collective female labor gave respectability and comfort to both buildings. In 1859 when the Methodist Revered N.G. McGaughey of Carroll Circuit, Louisiana thanked a woman for furnishing his parsonage, the editors of the New Orleans Christian Advocate interpreted her work as a model for the future, asking that their readers, “Be diligent—repent and build your preacher a house—a good one—and furnish it as a gentleman’shouse should be furnished.”[151] Gone were the days of missionary preachers struggling to make ends meet; the late antebellum preacher of the Gulf South would have a proper place to call home, one that reflected the status of the church in the community, largely thanks to the efforts of churchwomen.

Wartime Reflections on Antebellum Stewardship

In November 1862, Amanda Armstrong, president of the Female Financial Association of Fayette Circuit in Mississippi, gave a speech for the fourth anniversary of the association and, in front of mixed company, made the case for public female stewardship in the church. Addressing the common assumption “that ladies are not capable of doing anything aside from their Domestic duties,” Armstrong responded that “ladies have a proper sphere to move in, I candidly admit; but I do not think it it [sic] follows as a matter of course, that they should bury the talents which God has given them to improve.”[152] Protestant women throughout the late antebellum Gulf South successfully expanded their domestic sphere into the public space of their churches. White women turned domestic duties of sewing, cooking, furnishing, and hosting into fundraising for and furnishing of church buildings, and employed enslaved female labor to do all of the above as an extension of their own religious duty. In the urban Gulf South, some women of color were able to choose to be stewards of their own churches, adopting the same fundraising methods based in domestic duties and also finding female religious community organized around a higher calling.

Predating women’s fundraising and sewing societies to aid the Civil War effort, antebellum Protestant women in the Gulf South formed church aid societies in order to expand the physical presence of their churches and furnish them with all the trappings of mainstream respectability and hospitality. Episcopal women, as the wealthiest patrons with the most interest in creating spaces that reflected both their consecration and social status, were the most active, but Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian women invested in constructing churches that reflected their newfound mainstream status as well. From 1835 to 1861, at least fifty-five Episcopal, twenty-two Baptist, seventeen Presbyterian, and fourteen Methodist churches in the Gulf South—108 different churches in total—benefited from the collective fundraising efforts of their female church members. Countless other church buildings in the region owe their existence to individual female financial patrons—subscribers, subscription collectors, fundraisers, and donors of furnishing items and physical labor. Their labors served as a material expression of their faith and, as a rector declared of the ladies of St. Luke’s Cahaba, Alabama, a material expression of their “lively interest in the prosperity and increase of the parish.”[153] The churches women built and furnished were not just practical structures to shield the congregation from the natural elements; they were also permanent sacred spaces that embodied the respectability, reverence, and comfort their respective denominations prioritized as they transitioned from missions to mainstream churches—spaces that would define the religious geography of the Protestant Gulf South for decades to come.

Appendix

Figure 1. “Trinity Church,” wood engraving by Nathaniel Orr, based on sketch by Elizabeth Savage, The Spirit of Missions, Edited for the Board of Missions of The Protestant Episcopal Church, 19 (New York: Daniel Dana Jr., 1854), 4. Digital scan produced for author by the Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

Figure 2. Gaineswood plantation house, Demopolis, Alabama, built from 1843 to 1861, is an example of domestic Greek Revival architecture in the Gulf South concurrent with church construction. “Northeast view of front entrance. 1936 - Gaineswood, 805 South Cedar Street, Demopolis, Marengo County, AL,” photograph, 1936, Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS ALA,46-DEMO,1—6, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/al0370.photos.004005p/

Figure 3. Newbern Presbyterian Church, Hale County, Alabama, vernacular Greek Revival, built in 1848. Alex Bush, “FRONT ELEVATION - Presbyterian Church, State Route 61, Newbern, Hale County, AL,” photograph, July 31, 1936, Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, ABS ALA,33-NEWB,3--1, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/al0233.photos.002712p/.

Figure 4. West and East elevation view of Chapel of the Cross, Gothic Revival architecture. “Chapel of the Cross, Mannsdale, Madison County, MS,” sketch, January 1934, Historic American Buildings Survey, From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS MISS,45-MAND,1- (sheet 2 of 6), http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ms0058.sheet.00002a/

Figure 5. South elevation view. “Chapel of the Cross, Mannsdale, Madison County, MS,” sketch, January 15, 1934, Historic American Buildings Survey, From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS MISS,45-MAND,1- (sheet 4 of 6), http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ms0058.sheet.00004a/.

Figure 6. Faunsdale Plantation slave quarter, Marengo County, Alabama. Altairisfar, “Detail of one of the slave quarters, built in the Carpenter Gothic style,” December 31, 2007, photograph, accessed December 1, 2018, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5309557.

Figure 7. St. John in-the-Prairie Episcopal Church, original exterior, Carpenter Gothic architecture.

Alex Bush, “Front and Side View N.E. - Episcopal Church, County Road 4 (moved from original location), Forkland, Green County, AL,” photograph, January 10, 1935, Historic American Buildings Survey, From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS ALA,32-FORK,1--1, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/al0195.photos.002408p/.

Figure 8. Thomas K. Wharton, “Section through the Collector’s Room Custom House New Orleans,” sketch, 1854, from “Diary: 1853-1854,” Thomas Kelah Wharton Diaries and Sketchbook Collection, New York Pubic Library, courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed December 7, 2018, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-583c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Figure 9. Thomas K. Wharton, "Steel Chapel. Felicity Road New Orleans," sketch, 1854, from “Diary: 1853-1854,” Thomas Kelah Wharton Diaries and Sketchbook Collection, New York Pubic Library, courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed December 7, 2018, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-5815-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Figure 10. Detail of Baptismal Font with inscription “Suffer little children to come unto me and forbid them not for of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” “Chapel of the Cross, Mannsdale, Madison County, MS,” sketch, January 15, 1934, Historic American Buildings Survey, From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS MISS,45-MAND,1- (sheet 5 of 6), http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ms0058.sheet.00005a/

Figure 11. Interior nave and chancel of St. John in-the-Prairies Episcopal Church. Alex Bush, “Interior Toward Altar - Episcopal Church, County Road 4 (moved from original location), Forkland, Green County, AL,” photograph, January 10, 1935, Historic American Buildings Survey, From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HABS ALA,32-FORK,1--4,

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/al0195.photos.002411p/.

Figure 12. Christ Episcopal Church, Mobile, dressed for the Christmas season in the nineteenth century. E.W. Russell, “Reproduction of Interior of Christ Church Interior Prior To Storm of 1909 – Christ Episcopal Church, Church & Saint Emanuel Streets, Mobile, Mobile County, AL,” print, April 19, 1937, Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS ALA,49-MOBI,33-7,

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/al0423.photos.001508p/.

Figure 13. Original carpenter Gothic design with bell tower. Carol M. Highsmith, “St John’s Episcopal Church, Tuscumbua, Alabama,” digital photograph, 2010, George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-highsm- 08680, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010640493/.

Figure 14. An example of a porticoed Methodist parsonage built in the mid-nineteenth century in Forkland, Alabama, ten miles from Demopolis. Alex Bush, “Front View N.E. (Parsonage) – Methodist Parsonage, County Road 4, Forkland, Greene County, AL,” photograph, January 10, 1935, Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS ALA,32-FORK,3-1,

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/al0198.photos.002416p/.

[1]. T.S. Savage, The Spirit of Missions 19 (New York: Daniel Dana Jr., 1854), 5.

[2]. Ibid., 6-7.

[3]. For scholarship with this narrative, see Donald Mathews, Religion in the Old South (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1977); Gregory A. Schneider, The Way of the Cross Leads Home: The Domestication of American Methodism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); Cynthia Lyerly, Methodism and the Southern Mind, 1770-1810 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Christine Heyrman, Southern Cross(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997); Scott Stephan, Redeeming the Southern Family (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008).

[4]. For scholarship on northern female religious associations and sewing societies, see Nancy F. Cott,The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman's Sphere” in New England, 1780-1835 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 132-159; Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in America (New York: Knopf, 1985),109-156. For scholarship on the lack of these opportunities in the antebellum South, see Jean E. Friedman, The Enclosed Garden: Women and Community in the Evangelical South, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 6; Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 44; Victoria E. Bynum, Unruly Women: The Politics of Social and Sexual Control in the Old South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 8; Stephanie McCurry, Masters of Small Worlds: Yeoman Households, Gender Relations, and the Political Culture of the Antebellum South Carolina Low Country (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 173-174.

[5]. For examples of women fundraising to build and furnish churches in the urban South see Suzanne Lebsock, The Free Women of Petersburg: Status and Culture in a Southern Town, 1784-1860 (New York: Norton, 1984),225-226; Randy Sparks, On Jordan’s Stormy Banks: Evangelicalism in Mississippi, 1778-1876 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1994), 54; “The Good Sisters: White Protestant Women and Institution Building in Antebellum Mississippi,” Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, vol. 2., ed. Elizabeth Anne Payne, Martha H. Swain, and Marjorie Julian Spruill (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2010), 51-52; Barry J. Vaughn, Bishops, Bourbons, and Big Mules: A History of the Episcopal Church in Alabama (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013), 20-27; Wayne Flynt, Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998), 11-96; Angela Boswell, “The Meaning of Participation: White Protestant Women in Antebellum Houston Churches,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 99 (1995): 43-44; Jualynne E. Dodson, Engendering Church: Women, Power and the AME Church (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001), 48.

[6]. I use the term “mainstream” to refer specifically to the four largest Protestant denominations at this time: the Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal Churches. I employ the term “evangelical” to denote Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian Churches. This article does not address smaller dissenter evangelical movements including Primitive Baptists, Cumberland Presbyterians, and Disciples of Christ, or the Catholic Church, which was already an established denomination in southern Louisiana.

[7]. LeeAnn Whites downplays the significance of antebellum female church societies. She argues that patriarchal church structures “limited their possibilities for independent development” and contrasts antebellum female church societies with the widespread female activism and leadership opportunities in sewing and fundraising organizations during the Civil War. See Civil War as a Crisis in Gender (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1995), 51-52.

[8]. Gretchen Buggeln sees this movement to make churches more comfortable, welcoming, and homelike as part of the “cult of sensibility” and highlights women’s furnishing work in New England in Temples of Grace: The Material Transformation of Connecticut’s Churches, 1790-1840 (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2003), 129, 202-205. On this topic, see John E. Crowley, The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities and Design in Early Modern Britain and Early America (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

[9]. On this rhetoric, see Lebsock, Free Women of Petersburg, 209-210, 233; Cott,The Bonds of Womanhood, xxv, 149-159; Mary Ryan, Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790-1865 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 98-104; Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct, 109-156; Susan Dye Lee, “Evangelical Domesticity: The Woman's Temperance Crusade of 1873-1874” in Women in New Worlds: HistoricalPerspectives on the Wesleyan Tradition, vol. 1, ed. Rosemary Skinner Keller, Louise L. Queen, and Hilah F. Thomas (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1981), 293-309.

[10]. On female slaveholders taking credit for household labor performed by enslaved individuals, see Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household, 128-129; Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 2009), 21.

[11]. For scholarship on this transition, see Mathews, Religion in the Old South, 81-135; Sparks, On Jordan’s Stormy Banks, 87-114. For examples of male anxieties over church status, see W. C. Crane, Proceedings of the Southern Baptist Convention Convened in the City of Baltimore: May 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th (Richmond: H.K. Ellyson, 1853), 63; William Green, Journal of the Proceedings of the Thirtieth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi (Natchez: Daily Courier, 1856), 17.

[12]. Herman Duncan Cope, The Diocese of Louisiana, Some of its history, 1838-1888(New Orleans: A.W. Hyatt, 1888), 14; Mattie Pegues Wood, The Life of St. John's Parish, A History of St. John's Episcopal Church from 1834 to 1955 (Montgomery: The Black Belt Press, 1955), 30. Wood states that in Alabama between 1850 and 1860 Episcopal Church construction averaged $5,766 per building, for a total of eighteen buildings. I have added to that building total to cover the entire period from 1841-1861.

[13]. See Buggeln, Temples of Grace, 133-134.

[14]. On the Gothic Revival in the Anglican Communion, as well as for the theological and aesthetic explanations of the architectural movement in Oxford and Cambridge, see James F. White, TheCambridge Movement and the Ecclesiologists and the Gothic Revival (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1962).

[15]. White, The Cambridge Movement, 92-103, 181-191; Buggeln, Temples of Grace, 110-115; Peter W. Williams, Houses of God: Region, Religion, and Architecture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 64-67, 115-116. See also John Edward Joyner, “The Architecture of Orthodox Anglicanism in the Antebellum South: the Principles of Neo-Gothic Parish Church Design and Their Application in the Southern Parish Church Architecture of Frank Wills and His Contemporaries,” (PhD. diss., Georgia Institute of Technology, 1998).

[16]. Williams, Houses of God, 119.

[17]. Ibid., 120. On Greek Revival movement in Protestant churches in the northeast between 1845 and 1860, see Mark S. Schantz, Piety in Providence: Class Dimensions of Religious Experience in Antebellum Rhode Island (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), 228.

[18]. White, The Cambridge Movement, 92; Buggeln, Temples of Grace, 134. For an example of denominational competition in church building projects, see G. W. Sill, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi (Natchez: Natchez Courier, 1851), 45-46.

[19]. Article from TheMississippian, July 15, 1857, cited by John G. Jones, A Complete History of Methodism as Connected with the Mississippi Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Vols. III & IV 1846-1869 (Jackson, MS: Commission on Archives and History Mississippi Conference, United Methodist Church, 2015), 4:283.

[20]. William Reed Mills, “Copy of Subscription List to the Church,” 1854, Christ Episcopal Church Minute Book, 1853-1855, MSS. 1619, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana (hereafter cited as LLMVC).

[21]. John S. Walton, “Real Estate of Third P. Church in a/c with John S. Walton,” 1854, 1856, Session Minutes, 1847-1904, microfilm, reel 1, Third Presbyterian Church (New Orleans, LA) Records, Presbyterian Church Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA (hereafter cited as PCHS); Richard Campanella, “Reconsidering the Christopher Inn: a Site History,” Preservation in Print 44, no. 1 (February 2017): 12.

[22]. T. Kingsberry, “Minutes of the Proceedings of the Magnolia Baptist Church of Christ, 1852-1860,” p. 21, Magnolia Baptist Church (Claiborne County) Records, Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission, Leland Speed Library, Mississippi College, Clinton, MS (hereafter cited as MBHC); Richard J. Cawthon, Lost Churches of Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), 168.

[23]. William Green, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi used the phrase “pious liberality” in his annual reports,in William Green, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi (Natchez: Daily Courier, 1853), 14; William Green, Journal of the Thirty-first Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi (Natchez: Daily Courier, 1857), 40.

[24]. Green, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi, 14.

[25]. For pictures and description, see “Our History,” The Chapel of the Cross Episcopal Church, Madison, Mississippi, accessed December 1, 2018, http://chapelofthecrossms.org/about-us/our-history/.

[26]. Ibid.; William Green, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi (Natchez: Natchez Courier, 1852), 22.

[27]. Green, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi, 22; Green, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi,14.

[28]. Blake Touchstone argues that Episcopalians were the most likely of all Protestants to build plantation chapels in the antebellum Gulf South. He counts four Episcopal plantation chapels in Alabama, six to ten in Mississippi, and twelve in Louisiana. See Touchstone, “Planters and Slave Religion in the Deep South,” in Masters and Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 1740-1870, ed. John Boles (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1988), 118.

[29]. Quotation from G. W. Stickney, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Alabama (Mobile: Farrow, Stokes & Dennett, 1856), 21.

For other examples with similar language of praise and Christian duty, see William Green, Journal of the Thirty-second Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Mississippi (Natchez: Daily Courier, 1858), 45; Nicholas Cobbs, Journal of the Proceedings of the Twenty-ninth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Alabama (Mobile: Farrow & Dennett, 1860), 9.

[30]. Louisa M. Harrison, “The Request of Mrs. Louisa M. Harrison for the Consecration of Faunsdale Chapel,” in Record Book: Faunsdale Chapel, 1848 to 1861, p. 6, file 765.2.19, Faunsdale Plantation Papers, 1805-1975, Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL (hereafter cited as BPL); William Green, “Sentence of Consecration of Faunsdale Chapel, Marengo Co. Alabama,” in Record Book: Faunsdale Chapel, 1848 to 1861, p. 7, file 765.2.19, Faunsdale Plantation Papers.