The Second Great Awakening and the Built Landscape of Missouri

Samuel Stella

Samuel Stella is a Ph.D. student in religious studies at Columbia University.

Cite this Article

Samuel Stella, "The Second Great Awakening and the Built Landscape of Missouri," Journal of Southern Religion (21) (2019): jsreligion.org/vol21/stella.

Open-access license

This work is licensed CC-BY. You are encouraged to make free use of this publication.

Click here to access MAVCOR Journal site for the special issue.

In October 1803, James McGready and William McGee ordained Finis Ewing to preach in the Transylvania Presbytery.[1] Ewing’s ordination was irregular; he had not completed the two years of theological training required by the Presbyterian Church prior to his ordination.[2] Those who encouraged him to seek ordination were willing to overlook Ewing’s lack of training due to the desperate need for clergy in the region. Thanks to spreading revivals (a type of evangelical Christian meeting meant to effect conversions, often held outdoors and, in the early nineteenth century, characterized by enthusiasm, mass participation, and emotionality), the Presbyterian population was growing faster than ministers could be found to preach to them.[3] Not everyone agreed with the decision to ordain Ewing; in December 1805, the Kentucky Synod convened a commission, which ruled that Finis Ewing, along with eleven other recently ordained ministers, would no longer be permitted to preach as Presbyterians.[4] However, the defrocked ministers continued their revivalist preaching and by 1810, three of them, including Ewing, formed a new congregation, independent of the Presbyterian Church, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church.[5]

One factor leading to the expulsion of the twelve ministers and the eventual formation of the new Cumberland Presbyterian Church was a difference in attitude among Presbyterians toward the religious revivalism of their time. This revivalist enthusiasm of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century and the rapid growth of evangelical Christian movements like Baptists and Methodists that accompanied it are known today as the Second Great Awakening. Although Ewing and the Cumberland Presbyterians believed that revivals, like those initiated by their friend James McGready in 1800, were God’s holy work, many of their fellow Presbyterians did not. Furthermore, the revivalist Presbyterians worked on the frontier and wanted to emulate the success of uneducated Methodist preachers and their circuit system, which brought revival to geographically isolated communities.[6] One biographer of Ewing noted that he was intensely patriotic and had a special appreciation of the religious and civil liberties won in the American Revolution.[7] In short, Ewing’s brand of Cumberland Presbyterianism was part and parcel of what historian Nathan Hatch calls the “leaven of democratic persuasions” that transformed the social and religious landscape of the United States.[8]

In 1820 Ewing emulated the revivalists before him and, like many of his former congregants, left his home in Lebanon, Tennessee and travelled west to New Lebanon in Cooper County, Missouri. In doing so, Ewing participated in a specific migration pattern. New Lebanon was not the only community of transplants from the Upper South in central and eastern Missouri—a region still known today as “Little Dixie.”[9] Moreover, his was not the only such community to continue the social and religious practices and patterns developed “back home” or to build a particular style of church.

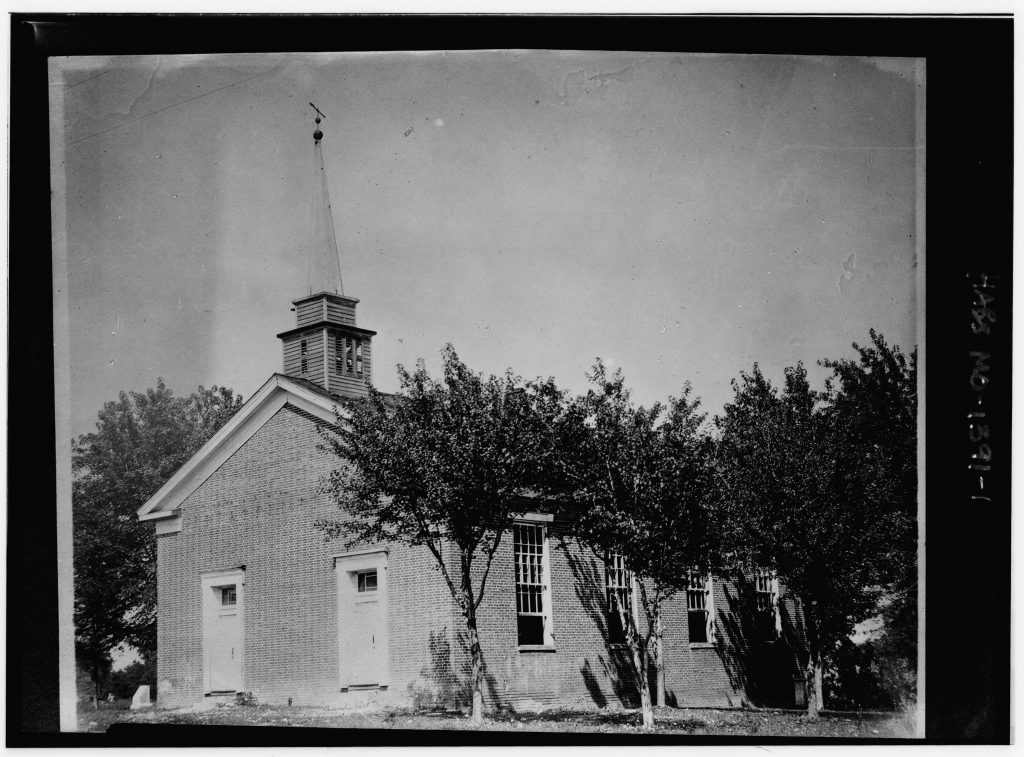

Today, New Lebanon Cumberland Church sits unused on Missouri Highway A (Fig. 2). It is a single story, red brick, rectangular building with a small belfry and spirelet above the front façade. This façade, which rises to a gable, contains two single doors that are mounted by identical transoms.The interior is a single room, divided by a low barrier down the center that originally functioned to separate men and women during services. Two iron stoves sit opposite each other in the side aisles halfway up the church; their pipes form an arch over the middle section of pews where they join and exit through the ceiling. The chancel matches the simplicity of the rest of the building; it consists of an old upright piano, a few simple chairs facing the pews, and a single lectern.[10] This style of building is called a gable-end church, a type that is a familiar sight to those who live in and traverse the backroads of mid-Missouri.

Many of these gable-end churches, like New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian, were built by congregations between 1803 and 1821, the period of settlement in Missouri that followed the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and continued through to the early years of statehood in 1821, however the gable-end form continued to be used until the end of the nineteenth century. According to the National Register of Historic Places’s application forms, these buildings are characterized by their formal similarities, which reflect a limited “vernacular” style.[11] It is my contention, however, that these formal similarities are not merely incidental but that their stylistic conformity reflects the theological, social, and aesthetic concerns of their builders.[12] Unfortunately, the literature on church architecture in the United States is generally silent on these churches. When scholarship does address them, it is condescending. For example, in Houses of God: Region, Religion, and Architecture in the United States, Peter W. Williams says this about religious architecture in the land between the Mississippi and the Rockies:

In terms of settlement patterns, most of the region was populated during the middle and later decades of the nineteenth century by a variety of peoples, none of them in sufficient intensity to sustain a “culture hearth.” A preoccupation with, at best, material prosperity – or, at worst, simply surviving under arduous climatic circumstances – has not usually created a surplus of resources to invest in “culture.” As a result, this entire region can be characterized negatively for our purposes as one which, though humanly interesting, has produced little distinctive or noteworthy by way of religious architecture.[13]

Even historians of vernacular architecture in the Little Dixie region of Missouri have ignored the gable-end church form.[14] Nonetheless, it is a mistake to conclude that the simplicity of these buildings resulted solely from the material circumstances of their construction. Even when necessity dictated form, the endurance of this type of church building—often the oldest on the landscape and sometimes in continuous use—demonstrates a significance that exceeds mere necessity.

This article argues that the simple, gable-end church form was suited to the material circumstances and to the socio-theological climate of the Second Great Awakening. Furthermore, gable-end churches provided an affective and sensorial locus for newly created communities to position themselves as extensions of an evangelical Protestant national consciousness. While nineteenth-century Protestant growth transected multiple boundaries of identity, those who often invested the most in extending a Protestant American consciousness through church building were white men. Indeed, the attempt to forge a single, Protestant, national consciousness was checked by realities of social hierarchies that were variously preserved or modified by specific church communities. Thus, some nineteenth-century Missouri church buildings included special balconies to seat—and segregate—enslaved blacks; others featured dual entrances and partitions to enforce strict gender segregation. That being said, marginalized groups also invested in the extension of a Protestant national consciousness as groups of freedmen built gable-end churches for their own communities. These freedmen attempted to extend an equanimous Protestant America that did away with the hierarchies that had previously made them slaves. Clearly, the exact contours of a Protestant America were not static, nevertheless, gable-end churches, and the congregations they housed, attempted to advance an American Protestant nation into territories recently acquired by the United States in the nineteenth century. The gable-end church became an icon of the process by which the Missouri territory became American.[15]

The Second Great Awakening is a difficult movement to define. The name references a previous period of religious revival in colonial America, the so-called First Great Awakening, and therefore suggests a repetition of the events of that period.[16] Indeed, the term “the Second Great Awakening” can be employed to describe a period of evangelical Christian revivalism that occurred in the early years of the American Republic from about 1780 to 1830, a period in which historians argue the United States as a newly formed nation-state was in a process of expiremental self-formation.[17] However, the transformations of the period clearly exceed any narrow definition limited to Christian revivalism. This paper follows and extends Donald Mathews in defining the Second Great Awakening as “in its social aspects an organizing process” rather than as a theological transformation or a period of emotional revivalism.[18] Mathews also anticipated later scholarship that dated the end of the Second Great Awakening to 1830. Problematizing the neat periodization of the movement, Mathews states,

The measure of the success of the Awakening was not in the length of various periods of enthusiasm however, even though many ministers of the time thought so. The measure was in the number of new churches organized which could persist when enthusiasm had died down.[19]

I argue the same principle applies to the duration of the Awakening as a historiographical epoch as well as to its success. Mathews recognizes that the persistence of church buildings matters. Instead of proposing an alternative date, I seek to mine the metaphor of “Awakening.” Divorced from its overtly theological cast, an awakening in the literal sense is a transitional period, a boundary between one state and another. In fact as a gerund, the term “awakening” not only forecloses its own conclusion, but is interminably processual. In this sense, both Great Awakenings can have no real terminus, even as some of the they phenomena they name waned or ceased. Instead, they are best understood as a continuing set of practices—Evangelical Christian revivalism—and, more importantly, as mnemonic devices that have persistently oriented American Evangelicals seeking a Protestant America. Thus, even the latest buildings that I examine, some of which were built at the end of the nineteenth century, are components of the organizing process that Mathews outlines.[20]

Mathews identifies the impetus for the organizing movement (hereafter the Awakening) as the “social strain” created by the process of state formation in the wake of the Revolutionary War.[21] Revivalism eased this strain; it “promised a ‘positive outcome in an uncertain situation’ for it proposed to make men better by putting them into direct contact with God.”[22] This contact with God was institutionalized in local units united by supralocal organizations. Thus, according to Matthews,

It was not a strong national organization that helped to make the churches important in the development of an American community, but the relatively strong local churches that shared common values and norms with their counterparts throughout the United States. The experience of participating in a small, local organization was more meaningful for Americans than any affiliation with a supralocal agency.[23]

Although this quotation is in the conclusion of Mathews’s paper, it contains concepts which help to flesh out his thesis. Matthews argues that the enthusiasm of a revival might drive up membership in a local church, which is able to persist because participation in a “small, local organization” was meaningful. In other words, Mathews challenges the idea that the Second Great Awakening was primarily a matter of revivalism, and was instead an organizing process, by arguing that belonging to a local church after a revival was part of what stitched together the patchwork of the nascent nation. He also emphasizes the importance of new American citizens’ experience at the local level, writing, “American nationalism in part, therefore, rested not on the power of a national institution so much as the relevance, power and similarity of thousands of local organizations that helped to create ‘a common world of experience.’”[24] Certainly, the built spaces in which people met, prayed, quarreled, married, and were buried must be considered a significant component of the sensory world of experience that Matthews described.

By combing the Missouri Department of Natural Resources’s list of accepted National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) applications, I was able to catalog twenty-six gable-end churches in Missouri.[25] Many of these applications were generated by the issuance of a NRHP Multiple Property Documentation Form. These forms publicize criteria for the types of properties that are eligible for registration with the NRHP. In 2010 the National Register Coordinator for Missouri, Tiffany Patterson, submitted a NRHP Multiple Property Documentation Form titled “Rural Church Architecture of Missouri, c. 1819 to c. 1945.”[26] In this document, Patterson writes, “Based on illustrations and extant church structures from the period (the nineteenth century), most rural religious buildings had rectangular footprints and a gable roof (gable-end type).”[27] She also provides a more comprehensive description of this church type:

[It is] characterized by its front-facing gable façade and symmetrical arrangement of fenestration. In most examples, the entrance is centered with single or double doors. However, two single-leaf entrances (two-door type) are not uncommon, notably in examples dating from c. 1840 to c. 1880. Transoms over doors are common features for all variations. Primary façades may have two windows flanking the central entrance. Additional fenestration on the primary elevation is by no means universal. Two-door examples generally do not have windows at the ground floor level. A round window in the gable is a common feature of the church type. Additionally, the type often has a short steeple with a four-sided spire at the peak of the gable roof.[28]

The very earliest Protestant churches built in Missouri, including the New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian Church, share these characteristics. As I will show, the popularity of the gable-end church was neither accidental, nor dictated solely by the material circumstances of rural life.

The first construction of a Protestant church in the Missouri territory was an event of extreme significance for those who built it and for subsequent generations of Protestants.[29] As the Baptist pastor and early historian of the Baptist Movement in Missouri, H.F. Tong, writes in 1888:

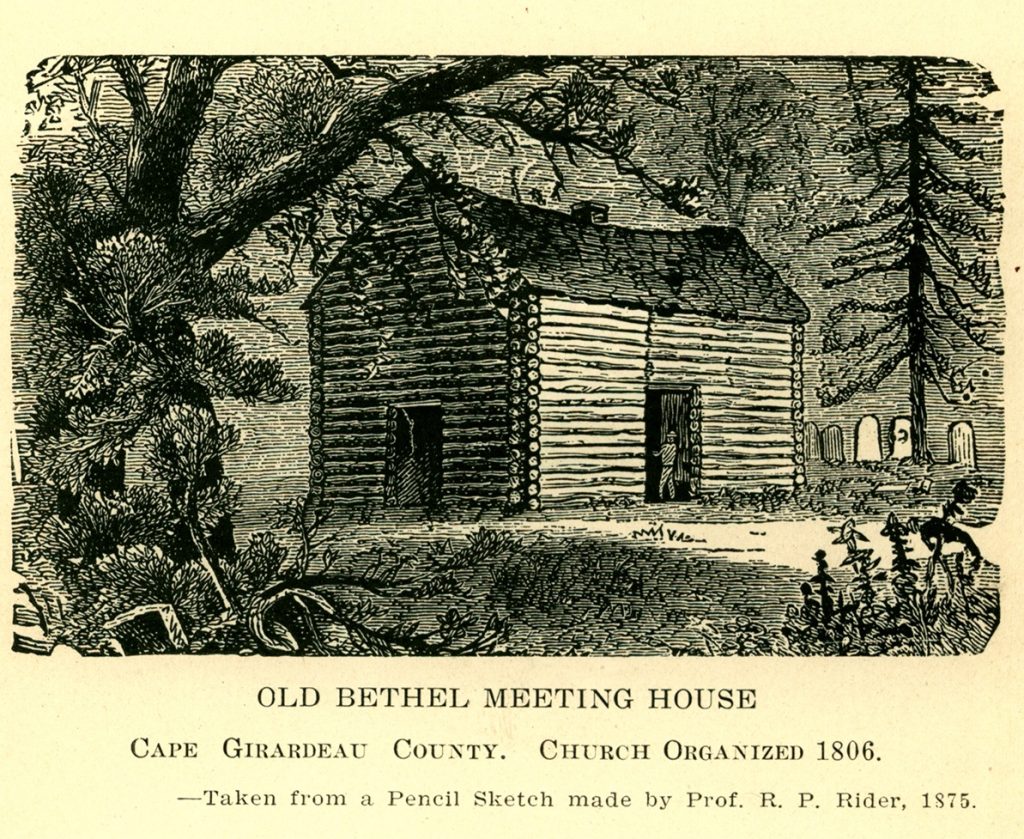

The first house of worship ever erected in Missouri, save those built by Catholics, was built by the Bethel Baptist Church above mentioned not long after its organization (1806). It was constructed mainly of very large yellow poplar logs, well hewn; it was about twenty by thirty feet, and located about one and a half miles south of Jackson.[30]

Tong goes on to quote a “highly complimentary [sic] address” given by Reverend J. C. Maple to the “Moderator of the General Association of Missouri, at its session held at St. Joseph, in October 1875.” Tong reports that Rev. Maple said:

It is known, my brethren, that, as in other States, the Baptists were among the first to erect the standard of the cross in Missouri; and though we are not of those who have faith in the preserving power of relics or amulets, we do believe in guarding with care our records . . . In 1806, the Bethel Baptist church was organized, and soon afterward a house was built, in which they met to worship God. This was the first house of worship built by anti-Catholics, west of the Mississippi River. From the great river to the Pacific Ocean this log house was the only building devoted to the service of the living God.[31] (See Fig. 3-4)

Here an act of narrating the construction of a simple, log church preserves the memory of the original moment of Missouri’s transformation from ungodly Catholic and French to pious Protestant and American. At the same time, the Reverend Maple’s speech expresses an uneasy awareness that reverence for the materiality of this building is similar to the dangerous material devotional practices that its construction was intended to supplant. Notably, Tong records that there were individual Baptists present in the area that is now known as Cape Girardeau County, Missouri as early as 1796 and also references a church organized in Tywappity Bottom, Missouri in 1805.[32] Tong does not treat these individual Baptists, however, in as much detail or with the same reverence as the first church building. For Tong, the material form of the single-room, gable-end, log church itself was significant in forming the world of experience shared by frontier Baptists.

It was not just Baptists who had meaningful early experiences in log-built, gable-end churches. McKendree Chapel, a Methodist gable-end style church also in Cape Girardeau County was built in 1819 for the express purpose of hosting the first Missouri Annual Conference which included territory in Illinois, Indiana, and Arkansas besides Missouri. At one point in its history it was covered with weatherboard, which would have made the building appear virtually identical to later frame-built, gable-end churches like the majority of those I have cataloged here.[33] W. S. Woodard’s Annals of Methodism in Missouri provides insight into this first Methodist construction in Missouri. Woodard quotes John Scripps, a circuit rider who was assigned to the Cape Girardeau circuit when McKendree Chapel was built:

It was this year (1819) that McKendree Chapel was built, a good hewed-log house, with a shingle roof, good plank floor, windows, etc. It was the first substantial and finished meeting house built for us in Missouri, by the hands of regular workmen, and was commenced and completed this year, with special reference to the first annual Conference ever held on the west side of the Mississippi river. It stands two miles east of Jackson and eight miles west of Cape Girardeau, in a camp ground hallowed by the recollections of happy hundreds, who have there been born again to sing redeeming love.[34]

Like Tong and Maple, Scripps expresses reverence for the “good hewed-log house.” Woodard goes on to note that McKendree “is still standing” and “the oldest meeting house in the state” (Fig. 5-6).[35] One hundred and twenty-three years later, this is still true. McKendree Chapel was listed on the NRHP in 1984, well before Patterson issued “Rural Church Architecture of Missouri.” The church’s registration forms show that from a very early time McKendree chapel was a meaningful place for Methodists in Missouri.[36] The document states, “The local circuit in their Quarterly Conference of October 30, 1869, resolved to maintain the McKendree Chapel; ‘the house will be to repair we do not wish to build a new house but preserve the old one.’”[37] Here, the aesthetically and theologically “good” building is preservedby Methodists as a memorial of their entry into and transformation of the Missouri territory.

Like Baptists and Methodists, Presbyterians also built and maintained prototypical gable-end churches in Missouri. Presbyterians did not see the same kinds of membership increases as the Baptists or the Methodists. Moreover, the tradition’slocation within a Calvinist, Reformed lineage, which emphasized the helplessness of sinners and the election of the saved, tempered Presbyterians’ enthusiasm for the emotional revivalism and nearly instantaneous experiences of salvation that are often associated with the Second Great Awakening. However, the Presbyterians who did employ revivalist techniques organized a significant number of local churches in territorial and early state Missouri.[38] The first of these was Bellevue, organized in present-day Caledonia, Missouri in 1816.[39] Salmon Giddings, a Congregationalist from Connecticut, organized this and six other churches.[40] Of these six, First Presbyterian of St. Louis and Bonhomme Presbyterian (now a member of the Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians) still remain as active congregations.[41] The second permanent structure to house Bonhomme Presbyterian, presently named the Old Stone Church, a gable-end, stone church constructed in 1840, is also extant (Fig. 7).[42] In 1832 First Presbyterian of St. Louis held a protracted meeting that was conducted by the noted Presbyterian revivalist and abolitionist, David Nelson.[43] According to historian Joseph H. Hall, “So remarkable was the display of grace that 128 new members were added to the church causing it to divide into daughter churches—Second Church in St. Louis and Des Peres in the county.”[44] The original building constructed for Des Peres in 1834, also a gable-end, stone building, is still standing today (Fig. 8).[45]

These three buildings—Old Bethel, reconstructed from an 1811 structure, McKendree chapel, built in 1819, and Des Peres church, built in 1834—are the oldest extant Protestant churches standing in Missouri. All three are a gable-end design. Notably, Bethel’s layout differs ever so slightly from McKendree chapel and Des Peres church; the entrance to the building is on the “long wall” not the gabled wall. According to the criteria outlined by Patterson in “Rural Church Architecture of Missouri,” this variation is sufficient to categorize Bethel as a type of gable-end subset called a side-gable church.[46] However, for the purpose of this discussion, this difference is irrelevant. Regardless of the positioning of their entrances, local churches in Missouri replicated the gable-end design and its variations because Evangelicals’ experience of worshipping in buildings of this form was symbolic of the organizing processes that were transforming the “frontier” into America, especially to the white men who imagined themselves first as agents of this process and later as its inheritors. This fact grounds claims that later gable-end churches, notably those built further west, are rooted in the Second Great Awakening and were icons of the new order that it organized.

Mount Nebo Baptist Church in Pilot Grove of Cooper County, Missouri was constructed in 1856, forty-five years after the second log Bethel was built (Fig. 9).[47] It is also not the first structure to house the Mount Nebo congregation. According to the NRHP registration form, the present building was the third to be built by the congregation, which was organized in 1820.[48] The first building was constructed, like Bethel and McKendree, from hewn logs. The second was built from a timber frame. Interestingly, even though it is the third building to house the church, the present building was built with the same design and technique as its predecessor and is not significantly different than the “prototypical” log or stone churches that came before it. The church is one story, gable-ended, with two single-door entrances. It has a short, tin steeple. The church’s interior originally included a small loft at the rear of the church, known as a slave gallery since its purpose was to segregate enslaved blacks from the white congregation below, which is still partially intact.[49] The catalyst for the construction of this third building seems to have been a growing congregation rather than changing frontier conditions, which meant that it was no longer necessary to have a simple structure. Like the two buildings before it, the extant building is a single rectangular chamber with minimal ornamentation. Rather than build a structure with an entirely new layout, the congregation simply constructed a larger version of the church that they had previously gathered in. Their congregation was growing and they needed more space. Still, the building committee set a size limit for the church—forty by seventy feet.[50] Since the church was growing rapidly enough to need a larger building, but, according to the church records cited by NRHP documents, explicitly limited the size of their new building, it appears that they were concerned that the church not be toobig.[51] What’s more, the congregation held a protracted meeting consisting of several consecutive days of revival services soon after this building was constructed.[52] This meeting generated nine conversions, further increasing the total membership of Mount Nebo and intensifying the demand of balancing growth with relatively small gable-end design.[53] Overall, Mount Nebo’s growth through revivalism and their construction of a permanent local organization materialized in a physical building is a good demonstration of Mathews’s argument that there is a strong, mutually reinforcing connection between churches as local institutions and the revivalism that generated their growth in the nineteenth century.[54]

Not far from Mount Nebo Baptist church is another gable-end church from the 1850s, New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian—Ewing’s church with which I began this paper.[55] Of the churches I examined, it has the most obvious and direct ties to what is conventionally considered the Second Great Awakening. New Lebanon began as the “New Lebanon Society” composed of settlers originally from Lebanon, Tennessee who established themselves in Cooper County, Missouri. These settlers were members of the original Lebanon Church in Tennessee, where Ewing had been pastor.[56] According to the NRHP registration documents, so many of Ewing’s Tennessee congregants moved to Missouri that he decided to join them in 1820. Initially, the New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterians held meetings outdoors or met in a log double-house on a piece of Ewing’s land set aside for camp meetings. The log building was torn down in 1859 to build the extant New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian Church.[57]

Completed in 1860, this building is a single-story, gable-end church constructed from pine frame and locally made brick.[58] It has two single-door entrances, intended to separate men and women, and a center row of pews partitioned down the middle for the same purpose (Fig. 2).[59] This building was also used as the civic hub of the New Lebanon Township, which grew until the 1890s. Today the building is seldom used and the Lebanon Cumberland Church congregation no longer exists. As with Mount Nebo Baptist, it is striking that the congregation met in a log structure for such a long time before building a brick church. Ewing, shortly after he moved to Missouri, built log houses for his family very near the log church. Ewing considered these log houses temporary lodgings while he built a large, multi-story brick home.[60] The log church, however, was different. Rather than being replaced like Ewing’s log houses, it was used for forty years despite the fact that its pastor (and probably some of its members) had the knowledge and ability to build larger, more complex, and more permanent structures. This suggests that something other than material and technological limitations were behind the simplicity of their church. When the Cumberland Presbyterians of New Lebanon did replace their log church with a brick one, they increased the size by 960 square feet and added a bell, but the core design remained the same. The church is constructed from bricks fired on site.[61] The red brick church did not have identical aesthetic qualities to the log one, but the change from log to brick simplified maintenance while still preserving the basic aesthetic forms necessary to provide the “shared experience” that Mathews claims organized the new nation. In other words, to almost every other Missouri Protestant, the experience of worshipping in a one room, gable-end, brick or frame church was not categorically different from worshipping in a log church.

The last gable-end church we will examine, is, not surprisingly, very similar to the prior churches considered, but it also has a significant difference. Built at the late date of 1883, Bond’s Chapel Methodist Church in Boone County, Missouri was the first and only structure used by the Bond’s Chapel congregation (Figs. 10–11).[62] The building is a wood frame, twenty-four by forty-three-foot rectangle with a small chancel projecting from the north wall.[63] It has a double-door entrance inside a vestibule, which was added in the 1940s to protect the old original doors.[64] Unlike many other small churches built at the end of the nineteenth century, the building was not built from a partially assembled, mail-order kit, but was constructed from lumber milled by the builders, who were also the church’s founders.[65] Of all the Registration Documents surveyed for this paper, the one prepared for this church was the only to suggest that the “primitive” design was informed by social and theological dictates rather than poverty or haste. The preparer of these forms, Dr. Bonnie Stepenoff, connects Bond’s chapel directly to McKendree. She writes:

The form of the church was similar to that of many early log and frame churches, such as the historic Old McKendree Chapel erected in 1818 in southeast Missouri, the cradle of Methodism in the state. In its simple, old-fashioned form and style of construction, Bond’s Chapel expressed the desire of the local congregation to cling to its pioneer roots.[66]

She goes on to quote John Wesley’s advice, which serves as the epigraph of this paper, saying “Let all preaching-houses be built plain and decent; but not more expensive than is absolutely unavoidable; otherwise the necessity of raising money will make rich men necessary to us.”[67] By the time Bond’s Chapel was constructed, Methodists, especially in urban locals, were building big expensive meetinghouses like the Wesleyan Grove cottages and tabernacle on Martha’s Vineyard. Nonetheless, the Bond Chapel exemplifies a continued desire to build simple meetinghouses like McKendree.

In light of Mathews’s thesis, one-room, gable-end churches with little more ornamentation than a belfry or steeple were ubiquitous in nineteenth-century Missouri because the form lent a commonality to the experience, not just of church-going, but of everyday life. As in other iconic regimes, there is variation between the buildings; some are brick, others are wooden, but their formal similarities connect them and make them easily recognizable as icons of the Second Great Awakening as organizing process. Even when Protestant Missourians encountered churches to which they didn’t belong, they recognized them as churches in an interlocking, dual sense. First, they recognized the formal elements of the gable-end building form as sacred architecture. Second, they linked this specific form of church to a world of experience in which they participated that was Protestant, American, and moving west. Thus, while many Protestants, especially preachers and missionaries, were committed to the superiority of their own denomination’s theology and practice, they nevertheless subordinated these concerns to an imagined, overarching evangelical Protestantism. Evangelical Protestant denominations, which quickly dominated the newly opened territory, are the ones that grew the most during the Second Great Awakening.[68] The fact that early Protestant Missourians could encounter each other’s sacred spaces and recognize those spaces as similar to their own also meant recognition of their neighbors’ shared values and norms.

Not all of their neighbors were fellow Protestants though. As Tong and Maple convey in their histories of Bethel, Protestants in Missouri thought of their participation in the American national project in terms of converting a previously Catholic territory. Missouri was claimed by France until the Louisiana Purchase and the region along the Mississippi River had been settled by French Catholics before Protestants arrived there. These French settlers organized parishes and built churches, some of which are also extant today. If the first wave of Protestants to settle in Missouri encountered these Catholic buildings, they likely imagined them as hyper-material temples of idolatry. As John Davis demonstrates, early-nineteenth-century American Protestants, at least on the East Coast, were particularly fascinated by representations of European Catholic interiors.[69] Based on the positive experiences that viewers of such representations reported and the genre’s overwhelming popularity, Davis argues that the Protestant display and consumption of these images complicated Protestant anti-Catholicism by creating an “empathetic experience of the body and the senses.”[70] At the same time, he observes that the reception of these images was often reported in print through familiar anti-Catholic tropes.[71] I would note that admiration and desire, and disgust and revulsion are not necessarily exclusive. What is important for this study is that nineteenth-century Protestants had access to materials that allowed them to imagine Catholic architecture against which to base their own.

If the earliest Missouri Protestants did encounter Catholic architecture in person, they would have found constructions like the Church of the Holy Family built in Cahokia, Illinois in 1799, located just across the Missouri river from St. Louis (Fig.12). Like McKendree Chapel and Bethel Baptist, this church and the other Catholic churches in the region were constructed from hewn logs. In this respect, it may seem similar to early Missouri Protestant churches. However, like the other Catholic churches in the region at this time, the Church of the Holy Family was constructed according to a distinct French Colonial style. These buildings were constructed from vertically arranged, closely spaced timbers, which were partially buried in the ground. The Church of the Holy Family also features architectural details like a small transept that distinguish it from comparable Protestant buildings. As architectural historian Herb Stovel remarked, “This church [Holy Family] is closer to the 17th Louisbourg Fortress in Nova Scotia than it is to anything in the U.S.”[72] Furthermore, Catholics in Missouri seemed to have updated their buildings more frequently in the nineteenth century than Protestants, often replacing earlier timber buildings with newer ones. For example, the oldest original Catholic building in the state, the convent attached to the Shrine of Saint Ferdinand, was built in 1819 using masonry. The shrine itself was built in 1821 and replaced an early log building.[73] It is ironic that Protestant chroniclers averred that their own reverence for early Missouri Protestant architecture was not like Catholic material devotion when nineteenth-century Missouri Catholics seem to have been relatively disinterested in preserving their old buildings.[74] Throughout the nineteenth century, Protestants in Missouri built churches differently than Catholics. More importantly, they imagined that their buildings were different and they developed a regional church architecture style largely premised on this imagined difference.

Returning to the attempt to extend a Protestant National consciousness, I want to take Mathews’s conclusions one step further. According to his hypothesis, the Second Great Awakening was an organizing process initiated to resolve the social strains felt by a new and growing nation.[75] It accomplished this by forming small local congregations which acted as voluntary societies. In the absence of civic bodies in the frontier, these church societies could carry out projects that required cooperation and coordination, like settling mundane disputes, or planning town development. According to Mathews, these local congregations afforded members an opportunity for collective, relatively democratic participation that mirrored post-revolutionary American political rhetoric.[76] Additionally, they could provide a shared world of experience that lent the impression of common values among the class of white Protestant men who sought to transform the “frontier.” If this process was largely successful in providing an initial period of stability—at least from the point of view of those who underwrote it—until other processes of social organization (like industrialization, and urbanization) took over, we might rightly wonder what became of the structures—material and social—created by and constitutive of this process. Answering this question in full is beyond the scope of the current project, but I propose that the endurance and reproduction of small gable-end churches—variations of the kinds of meetinghouses used in early revivals back East in places like the Cumberland region of Tennessee and Kentucky and those initially built in the Missouri territory—provides an initial and localized step in an exploration of the material structures that organized the early American state. Specifically, for white Protestants invested in the American national project, these structures functioned as resources that they could use when they faced new social strains. Simultaneously, the gable-end church form could be a resource for black people for whom the American national project initially entailed enslavement. In Missouri, and of course elsewhere, slavery, the Civil War, emancipation, and reconstruction were such strains, challenging the cohesion of the American Republic, and the gable-end church was employed to shore up a floundering Protestant national vision.

Of the twenty-six gable-end churches I cataloged, twelve were built after the Civil War. Many of these are in the Little Dixie region and a surprising number were churches organized by newly emancipated, formerly enslaved people.[77] New Lebanon Church is a good demonstration of the settlement patterns typical of “Little Dixie.” The boundaries of this region are fluid but the term generally refers to land west of St. Charles County along the Missouri River. The region was settled by people from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia who attempted to recreate the societal patterns of the upper South, including a plantation system based on the labor of enslaved Africans.[78] Many of the white people who lived in this region were sympathetic to the Confederacy and resisted the Union forces deployed to the area during the war. As a result, several churches were destroyed by battle or, if they were pro-Union, burned by guerillas. Other congregations suspended operations during the Civil War and decided to rebuild their meetinghouses in the reconstruction period.[79] Like the churches rebuilt by white congregations, churches built by African American congregations during this time reproduced the form of church building common in antebellum Missouri (Figs. 13–14). One difference, though, was that slave galleries became less common in new churches. Some existing churches similarly removed theirs because they had become obsolete.[80] The reproduction of small, gable-end churches during reconstruction would have reminded Missourians of the stability they had sought in the early decades of their state. The fact that newly emancipated African Americans also reproduced this form indicates a desire to participate in the American Republic, as Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal church, certainly did.[81] As historian Richard S. Newman argues in Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers, Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal church, together with a community of black leaders in Philadelphia, linked their calls for emancipation and full civic integration of blacks to the evangelical Christian organizations they organized and operated. Individuals including Allen argued that Black participation was, in fact, crucial if the American Republic was to survive because it could uniquely provide the nation with some semblance of moral legitimacy in the wake of slavery.[82] African American use of the gable-end form in Missouri would have given their white neighbors, who had previously held them in bondage, the impression that they, as newly emancipated neighbors, intended to share their values and their investment in the American national project. White congregations that built in the gable-end style may have done so in an attempt to reaffirm the collective identity they had initially attempted to forge in Missouri. It seems likely, then, that the proliferation of gable-end churches in Missouri during the decades after the Civil War was a return to and reengagement with an icon of the organizational process that had previously turned strain into stability.

Finally, I want to look at how and why these churches have persisted into the present, both materially and in social imagination. I use the category “icon” to relate these buildings to each other, to the Awakening, and to their historic users. I claim that simple, gable-end churches are symbols of Missouri’s earliest Protestant settlements, linking Missouri to national myths of manifest destiny and the promise of a Protestant, Republican utopia—the aspirations of the Second Great Awakening as organizing process. This is certainly present in the romantic recollection of “Old Bethel” as the western outpost of Christendom in the works of early chroniclers of Protestant history like Tong and Maple, cited above.[83] It is not surprising, then, that these symbolic buildings have survived. Most of the churches I’ve discussed here no longer serve active congregations. Some were registered with the NRHP precisely because their small congregations knew that they would not last much longer.[84] At present, the buildings do not provide a “uniform world of experience” as they once did. Consequently, they have become available as open symbols. Indeed, this is a feature of iconic regimes generally. The stability of their significance is grounded in the ritual communities that generate and use them. When those communities change or dissolve, their icons become untethered and open to new interpretation. Today Missouri’s gable-end churches can easily represent instability, inequality, and tragedy. They can take on the political valence of a backwards-looking conservatism that is nostalgic of the Protestant nationalist promise they once represented.[85]

David Morgan asserts that “For many conservative Protestants, such unabashedly material forms of worship as . . . traditional church architecture . . . configure the sacred in an all too concrete way.”[86] He suggests that instead of instantiating the divine in space, as these material forms might do for other kinds of Christians, Protestant material forms help Protestants remember and narrate the divine in their own histories.[87] This is clearly the case for Tong and Maple, and for Woodard and Scripps, who narrate their divine histories through Old Bethel and McKendree Chapel, respectively. Maple even makes the hallmark disclaimer that although Old Bethel symbolizes the sacred, is not itself sacred. The unease that Protestants feel towards material forms of worship, coupled with a historic narrative in which Protestants reclaim Missouri from Catholics, helps to explain the utter simplicity of Missouri’s gable-end churches. These churches are, in a sense, minimalist. They drawing as little attention to their own materiality as possible and are built with few symbolic elements. They are churches built in contradistinction to the imagined, hyper-material, idolatrous Catholic churches that Missouri Protestants were so proud of displacing.

The gable-end churches which dot Missouri’s rural landscape are noteworthy because they literally structured the far-western front of the organizing process that Mathews claims to be the Second Great Awakening.[88] Their “primitive” form is not reducible to material circumstance. Their builders and those who worshipped in these spaces considered plain, unadorned construction to be ideal. Church builders reproduced this form across the territory because it allowed Missourians to assume that their neighbors held the same values and abided by the same norms as they did.

The organizing process of the Awakening changed the way that Missourians experience their landscape. The inverse is also true; the shared experiences of people worshiping in these buildings also contribute to our understanding of the Second Great Awakening. Historians studying the Second Great Awakening in the upper south and the frontier should not exclusively treat mechanisms of revival like camp meetings, or circuit riders, but remember that revivals were pipelines into regular church membership. The post-revival phase has to be considered if we are to understand the Second Great Awakening as a whole. To that end, I hope to have complicated the typical periodization of the Second Great Awakening. If Mathews’s hypothesis that the Second Great Awakening was an organizing process that attempted to coalesce an early American nationalism is accepted, the period must be as long as that process, perhaps even ongoing.[89] In this study, that process continued well into the nineteenth century.

This study demonstrates the substantial information that built material structures can convey to the historian about human experience. Following in the trails blazed by scholars like David Morgan and Henry Glassie, I have turned my attention to objects that have largely been dismissed as “vernacular” or “vulgar.” In the case of Missouri’s rural churches, the “vernacular” form was a profoundly meaningful one, and those who built and used them did so for complex reasons. Probing and comparing these churches shows that they extended the Second Great Awakening’s Protestant nationalism into the expanding western edges of the country. As Horace Bushnell imagined in his address to the American Home Missionary Society in 1847, “the emigrant, wherever he strays, remembers that he is an American still. He looks out from his hut of logs on the Western border, and feels the warmth of a distinct nationality glowing round him.”[90] Bushnell was concerned that this warm nationality couldn’t sustain the social integrity of the rapidly expanding country. He thought that in order for that nationality to survive, his hypothetical frontiersman needed to look out his window and see a church. By the end of the nineteenth century, that goal had been accomplished in Missouri.

Appendix

Figure 1: White Cloud Presbyterian Church, Callaway County, Missouri Department of Natural Resources photo. Tiffany Patterson, Photographer. Location: State Route F and CR 232, Callaway County, MO.; Materials: limestone, wood, asphalt; Date: 1880.

Figure 2. New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian Church, Cooper County. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS MO-1391. Location: State Road A, New Lebanon, MO. Cooper County; Materials: local brick, wood; Date: 1860.

Figure 3. Illustration of the First Old Bethel, Cape Girardeau County. From J.C. Maple, “Missouri Baptist Biography: A Series of Life-Sketches Indicating the Growth and Prosperity of the Baptist Churches as Represented in the Lives and Labors of Eminent Men and Women in Missouri.” Materials: Engraving from a pencil sketch by R. P. Rider, 1875.

Figure 4. Reconstruction of the Second Old Bethel Church, Cape Girardeau County. James Baughn, Photographer. Location: Jackson, MO. Cape Girardeau County; Materials: yellow poplar logs, glass; Date: 1812 (reconstructed 2006).

Figure 5.Exterior of McKendree Chapel, Cape Girardeau County. Ken Steinhoff, Photographer. Location: Off of Interstate 55 near Jackson, MO. Cape Girardeau County; Materials: granite, glass, poplar logs; Date: 1819.

Figure 6. McKendree Chapel Interior, Cape Girardeau County. Ken Steinhoff, Photographer. Location: Off of Interstate 55 near Jackson, MO. Cape Girardeau County; Materials: granite, glass, poplar logs; Date: 1819.

Figure 7. Bonhomme Presbyterian Church, “Old Stone Church,” St. Louis County. Donald A. Wallace, photographer. Location: Conway Road and White Road, Chesterfield, MO., St. Louis County; Materials: stone, brick, glass, plaster; Date: 1841.

Figure 8. Des Peres Presbyterian, St. Louis County. Photographer unknown. Location: Geyer Road, Frotenac, MO., Saint Louis County; Materials: limestone, cement, glass, wood; Date: 1834.

Figure 9. Mount Nebo Baptist Church, Pleasant Green, MO., Cooper County. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS MO-1395. Location: Pilot Grove, MO., Cooper County; Materials: brick, stone, wood, glass, tin; Date: 1857.

Figure 10. Bond’s Chapel Methodist, Boone County. Benjamin Herrold, photographer. Location: Missouri Route A. Hartsburg, MO., Boone County; Materials: wood, weatherboard, concrete, asphalt, glass; Date: 1884.

Figure 11. Bond’s Chapel Methodist, Boone County. Missouri Department of Natural Resources Photo. Bonnie Stepenoff, photographer. Location: Missouri Route A. Hartsburg, MO., Boone County; Materials: wood, weatherboard, concrete, asphalt, glass; Date: 1884.

Figure 12. Church of Holy Family. Saint Clair County, Illinois. Photographer unknown. Location: East 1st Street, Cahokia, IL., St. Clair County; Materials: black walnut logs, rubble, clay, white oak timbers, glass; Date: 1799.

Figure 13. Campbell Chapel AME, Howard County. Photographer unknown. Location: 602 Commerce Street, Glasgow, MO., Howard County; Materials: brick, asphalt, glass; Date: 1865.

Figure 14. Oakley Chapel AME, Callaway County. Missouri Department of Natural Resources Photo. Roger Maserang, photographer. Location: Intersection of Country Roads 485 and 486, Tebbetts, MO., Callaway County; Materials: concrete, wood, vinyl, asphalt, glass; Date: 1878.

[1] The Transylvania Presbytery originally encompassed Kentucky and parts of Tennessee.

[2] Ewing and his co-ordinands also expressed reservations about the Westminster Confession. Specifically, they were troubled that the confession taught “fatalism.” Indeed, the Cumberland Presbyterian church came to see itself as somewhere between Calvinism and Arminianism. Thomas H. Campbell, Studies in Cumberland Presbyterian History (Nashville: Cumberland Presbyterian Publishing House, 1944), 130-31.

[3] Campbell, 61.

[4] Campbell, 70-72.

[5] Richard Beard, Brief Biographical Sketches of Some of the Early Ministers of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church (Nashville: Cumberland Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1867), 35.

[6] Campbell, 62. I will use the term “frontier” throughout this paper to designate the western boundary of an expanding nation as it was constructed by self-styled Americans during the nineteenth century. I do not mean to indicate that such a boundary was essential or determined or that it was a real geographical limit beyond which humanity had not flourished. Indeed, I will show that the “frontier” of Missouri was claimed and inhabited by French and Spanish Catholic colonists before any Protestants ever arrived there. It was also the home territory of several indigenous nations and had been so since prehistory. The “Americans” who I am studying violently displaced them all. “Frontier” is thus a colonial category, which designated the zone of contact between those expanding a political hegemony and those whom it would exclude. I use the term because the subjects I am studying did imagine that it was essential, determined, and in every sense, real.

[7] Beard, 44-45.

[8] Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 195-96.

[9] Howard W. Marshall, Folk Architecture in Little Dixie: A Regional Culture in Missouri (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1981).

[10] Janice R. Cameron, “New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian Church and School” (United States Department of the Interior, July 1979), 2.

[11] Tiffany Patterson, “Rural Church Architecture of Missouri c. 1819 to c. 1945” (United States Department of the Interior, December 2010) 4.

[12] “Vernacular architecture” can easily become a shorthand description not unlike the category of “folk,” which locates the thing it describes at the bottom of a cultural hierarchy. It can also communicate that the entire meaning of the thing it denotes is available at the most superficial level of observation. Consequently, the “vernacular” has historically been considered unworthy of serious study. Alternatively, scholars like Henry Glassie have reclaimed the category. Glassie writes, “We find that important buildings can be interpreted as displays of the values we value—grandeur, perhaps, or originality—while unimportant buildings display values that we have not yet learned to appreciate. . . . We call buildings ‘vernacular’ because they embody values alien to those cherished in the academy.” Henry Glassie, Vernacular Architecture (Philadelphia: Material Culture, 2000), 20.

[13] Peter W. Williams,Houses of God: Region, Religion, and Architecture in the United States (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 210.

[14] Howard W. Marshall’s Folk Architecture in Little Dixie is an excellent treatment of “vernacular” architecture in the region following Glassie’s usage of the term. Although, Marshall demonstrates that nineteenth-century “folk” homes and barns in Little Dixie were built in an array of styles, he makes only a passing mention of a single church building. His observations further suggest that the tendency towards conformity among Little Dixie’s churches is rooted in some kind of normative aesthetic consciousness.

[15] “Icon” and “iconicity” will be important analytic terms for this paper. I follow Kathryn Lofton in broadly defining icons as “multivalent objects and ideas, simultaneously engendering ritual worship and being engendered by such ritual adoration.” Kathryn Lofton, Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 13-14.

[16] Jon Butler, “Enthusiasm Described and Decried: The Great Awakening as Interpretative Fiction,” The Journal of American History 69, no. 2 (1982): 305-25, doi:10.2307/1893821.

[17] I take this periodization from Hatch’s The Democratization of American Christianity. See also Paul E. Johnson, The Early American Republic, 1789-1829 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[18] Donald G. Mathews, “The Second Great Awakening as an Organizing Process, 1780-1830: An Hypothesis,” American Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1969): 27, doi:10.2307/2710771.

[19] Mathews, 35–36.

[20] Here, I mean to suggest that the process continues, albeit in a ghostly form, when people return to and invoke the process and ideals of this organization in order to orient their contemporary projects of national identity. Charles McCrary makes a similar argument concerning the proliferation of Methodist circuit rider autobiographies in the mid to late-nineteenth century, which he contends invoked memories of early Methodist zeal in order to re-orient the Methodist denomination. Charles McCrary, “The Myth of the Circuit Rider: American Methodist Autobiography and the Croaks of Nostalgia,” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 100, no. 1 (2017): 54-87, doi:10.5325/soundings.

[21] Donald G. Mathews, 32-33.

[22] Ibid., 34.

[23] Ibid., 42-43.

[24] Ibid., 43.

[25] This is not an exhaustive list of such churches; there are many churches of this type which remain unregistered. Further research in this area would seek to comprehensively catalogue extant nineteenth-century churches in rural Missouri.

[26] Patterson, “Rural Church Architecture of Missouri c. 1819 to c. 1945.”

[27] Ibid., sec. E.

[28] Ibid., sec. F.

[29] Protestants were not permitted to build churches in Missouri before it became U.S. territory in 1804.

[30] H. F. Tong, Historical Sketches of the Baptists of Southeast Missouri (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Company, 1888), 13.

[31] Ibid., 14-15. The fact that Bethel was reconstructed furthers the case that the physical building itself, not just tales of its past, constructs the historical memory of Missouri Baptists.

[32] H. F. Tong, 10.

[33] Marybelle Mueller, “McKendree Chapel, Cape Girardeau County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, August 1984), 2.

[34] W. S. Woodard, Annals of Methodism in Missouri: Containing an Outline of the Ministerial Life of More than One Thousand Preachers, and Sketches of More than Three Hundred: Also Sketches of Charges, Churches and Laymen from the Beginning in 1806 to the Centennial Year, 1884, Containing Seventy-Eight Years of History (Columbia, Mo.: E. W. Stephens, 1893), 32. See figures 5-6 for photographs of McKendree Chapel.

Circuit riders were licensed preachers in early Methodism that travelled great distances on horseback between churches in a territory, or circuit, that did not have their own preachers.

[35] Woodard, 33.

[36] Mueller, “McKendree Chapel, Cape Girardeau County, Missouri.”

[37] Marybelle Mueller, 3.

[38] Most of the very early growth of Presbyterianism in Missouri, Cumberland, and otherwise seems to have involved these techniques indicating that there was not an early “old-school” Presbyterian presence.

[39] Joseph H. Hall, Presbyterian Conflict and Resolution on the Missouri Frontier (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 1987), 3.

[40] Rockne Myers McCarthy and Charles A. Maxfield, “Presbyterian Pioneers: The Laity, Salmon Giddings and the Presbytery of Missouri,” American Presbyterians 69, no. 1 (1991): 1. It is worth noting that Samuel Giddings, a Congregationalist from Connecticut, organized Presbyterian churches according to the 1801 Plan of Union, under which Presbyterians and Congregationalists united to evangelize the frontier. This same alliance precipitated the “old-school” and “new-school” split among the Presbyterians with the “new-school” embracing the revivalist techniques and modified Calvinism of the Congregationalists and the “old-school” party representing a conservative position.

[41] Hall, 4.

[42] M. Patricia Holmes, “Bonhomme Presbyterian Church, St. Louis County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, December 1972), http://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/nps-nr/73002274.pdf.

[43] Nelson also wrote some popular hymns, founded Marion College, the first college in Missouri, and eventually left Missouri for Illinois due to the hostility he experienced in Missouri for his staunch abolitionism. Significantly, he was originally from Tennessee and seems to have come into contact with some of the early-nineteenth-century revivalism there. William A. Richardson, “Dr. David Nelson and His Times,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984) 13, no. 4 (1921): 433-63.

[44] Hall, 37.

[45] Noelle Soren, “Des Peres Presbyterian Church, St. Louis County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, December 1977), http://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/nps-nr/78003137.pdf.

[46] Patterson, sec. f.

[47] James M. Denny, “Mount Nebo Baptist Church, Cooper County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, May 1986), http://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/nps-nr/86001111.pdf.

[48] Ibid., 7.

[49] Ibid., When this building was constructed, its members could legally own slaves, thus the slave gallery was initially used to maintain a segregation at the heart of Anglo-American settlement in this region of Missouri. The gallery was partially removed in 1888, which suggests that after the end of slavery in Missouri in 1865, segregation was no longer enforced and/or freedmen left Mount Nebo. That the gallery was built in the first place, shows how some meant for the extension of a Protestant national consciousness to go hand in hand with a white supremacist social order. This version of America was white, slave owning, and Protestant.

[50] Ibid., 2.

[51] Ibid., 7.

[52] Ibid., 8.

[53] Ibid., 4.

[54] Mathews, 4.

[55] Cameron, “New Lebanon Cumberland Presbyterian Church and School”

[56] Ibid., 8.

[57] Ibid., 9.

[58] Ibid., 10.

[59] Ibid., 5.

[60] Ibid., 8.

[61] Ibid., 4.

[62] Bonnie Stepenoff, “Bond Chapel Methodist, Boone County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, July 25, 1992), 7, http://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/nps-nr/93000940.pdf.

[63] Ibid., 5.

[64] Ibid. Significantly, the building’s users have chosen the option to preserve—at the cost of additional construction—rather than to replace the church’s doors.

[65] Ibid., 7.

[66] Ibid., 1.

[67] Ibid., 7.

[68] The Christian Church was also an early presence in Missouri, but few of their early church buildings survive, so they have not made it into the NRHP.

[69] John Davis, “Catholic Envy: The Visual Culture of Protestant Desire,” in The Visual Culture of American Religions, ed. David Morgan and Sally Promey (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2001), 105-28.

[70] Davis, 128.

[71] Davis, 125.

[72] Patricia Rice, “Expert on French Heritage Examines Cahokia Church; Activist Pursuing ‘Heritage’ Status for Area Buildings.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 3, 1994.

[73] Theresa Tighe, “Florissant Shrine’s History Includes St. Rose, Father DeSmet,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 2, 1999.

[74] Interestingly, Catholics in St. Charles, Missouri recently reconstructed a historic log church there, St. Charles of Borromeo. According to the parish website, http://www.borromeoparish.com/parishHistory.php(accessed 10/5/2018) this building is a replica of one that has not been used since sometime in the early nineteenth century. Without straying too far from the scope of this article, I would suggest that this recent reconstruction is a direct engagement with the memorializing power of Protestant log structures.

[75] Mathews, 32-33.

[76] Mathews.

[77] Doris Handy, Tiffany Patterson, and Kris Zapalac, “Oakes Chapel AME, Callaway, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, October 2008), http://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/nps-nr/08001192.pdf; Rhonda Chalfant, “Campbell Chapel AME, Howard County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, October 1997), http://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/nps-nr/97001427.pdf.

[78] Chalfant, “Campbell Chapel AME, Howard County, Missouri,” 8.

[79]Noelle Soren, “Glasgow Presbyterian, Howard County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, August 1981); Denny.

[80] Denny, 3.

[81] Richard S. Newman,Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers(New York: New York University Press, 2008).

[82] Ibid., 74.

[83] Tong.

[84] Denny, “Mount Nebo Baptist Church, Cooper County, Missouri,” 4; Betty Lou Wallace McAtee and Tiffany Patterson, “White Cloud Presbyterian Church and Cemetery, Callaway County, Missouri” (United States Department of the Interior, 2010), 11.

[85] For example, Thomas Kinkade combines the landscapes of the Rocky Mountains with “English” cottages and gable-end churches to represent his sacred, nationalist vision. See “The Forest Chapel” or “Streams of Living Water.”

[86] David Morgan, Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images (Berkeley,: University of California Press, 1998), 181.

[87] Ibid., 183.

[88] Much more work could be done with these churches. For example, I have not been able to make a detailed account here of the connection between simplicity in building and the kind of populist political spirit that Nathan Hatch demonstrates in The Democratization of American Christianity, though this connection surely exists. I also have not addressed the specific theological underpinnings that occasioned a preference for simplicity, though this was also a factor in the popularity of gable-end churches. Moreover, I have not treated the impressive number of African-American churches organized in Missouri after emancipation, nor the experience of racial and gender segregation in Missouri churches before that. Future work on the subject would also probe the ways in which these buildings continue to mediate affects and meanings and would present and connect the flows of people, ideas, and built environments between Missouri and other places (re)made by the Second Great Awakening.

[89] I must also distinguish between the organization of a kind of nationalism and of a nation. I do not mean that the Second Great Awakening successfully forged the nation it had envisioned, only that that it intended to do so. Thus, when gable-end churches were taken as icons of a national character of shared, evangelical protestant values, it was experienced—to a degree—as a real fact, but also obscured the instability of such a universal, national project. Those Catholics in Saint Louis that so concerned Missouri’s first Baptists never went away, and the slave galleries in Little Dixie became obsolete as the enslaved people they once held were emancipated and quickly left these churches behind.

[90] Horace Bushnell, Barbarism the First Danger (New York: American Home Missionary Society, 1847), 17.